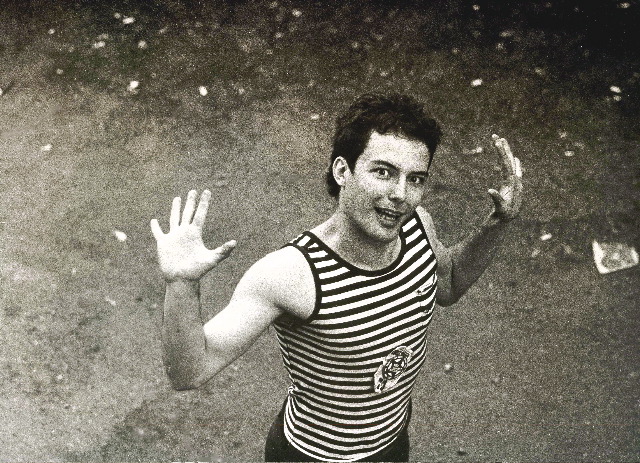

Jonathan Swift, Mark Twain, Oscar Wilde . . . Jello Biafra?! The Dead Kennedys’ acerbic frontman deserves to be placed in such rarefied comedic company by virtue of the three-minute satirical missiles he fired off during his band’s reign of (counter)terror between 1979 and 1986. Showering their targets with blasts of political parody, the Dead Kennedys (or DK, as in “decay”) lyrically shamed and maimed with the most subversive strains of moral indictment.

Jonathan Swift, Mark Twain, Oscar Wilde . . . Jello Biafra?! The Dead Kennedys’ acerbic frontman deserves to be placed in such rarefied comedic company by virtue of the three-minute satirical missiles he fired off during his band’s reign of (counter)terror between 1979 and 1986. Showering their targets with blasts of political parody, the Dead Kennedys (or DK, as in “decay”) lyrically shamed and maimed with the most subversive strains of moral indictment.

A more geo-specific context for the Dead Kennedys’ art is their home city, San Francisco, and state, California. Only a decade removed from the center of the hippy counterculture when they formed, the band was imbued with the freedom-seeking drives of that movement, though they expressed their dissatisfactions in a more aggressive fashion. When one recalls songs like “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to- Die Rag,” by fellow San Franciscans Country Joe McDonald & the Fish, we see the same strategies of parody employed in the service of sociopolitical purpose. A few years after Country Joe wrote his song, the use of parody was refined by another Californian, Randy Newman. His adoption of the voices of hypocrites and oppressors in order to shame them ushered in a proto-punk attitude, if not sound. By the late seventies, California (especially Los Angeles) had caught the punk bug, one particularly influenced by the irreverent and sarcastic screeds emanating from the London-based scene. DK both rode the wave of California’s early (proto) punk expressions and helped develop the subsequent hardcore scene, invigorating each with their own brand of biting wit.

As with the best satirists, Jello Biafra’s writing was born of anger and frustration as much as the desire to entertain. As the Reagan administration brought about a climate of fear and hysteria in its early years, so the Dead Kennedys exposed its political manipulations by echoing them in exaggerated lyrical scenarios, a warbling Orwellian vocal delivery, and a sinister musical backdrop. As he spat through his oppressors’ voices, Jello Biafra questioned, provoked, teased, and prodded, all the time with a sardonic, sneering grin reminiscent of Johnny Rotten.

The band’s name gave audiences an early indication of the type of humor that was in store for them. Many considered “Dead Kennedys” to be a sick and insensitive moniker; Biafra, though, regarded it as a metaphorical reflection on the death of the American dream. Such (mis)interpretation would prove to be a constant factor in the band’s contention-filled career. In order to circumvent the objections of club owners in their early gigging days, the band often played under various pseudonyms, among them the Sharks, the Creamsicles, and the Pink Twinkies. These playfully ambiguous (or ambiguously playful) names hilariously betrayed the harsh satirical barbs audiences were faced with once the band hit the stage. Indeed, those shows were never lacking in the band’s patented practical humor. At one gig in 1984, the band came onstage wearing Klan hoods, then removed them to reveal Reagan masks. Such guerrilla performance art alluded to the antics of the sixties Berkeley protest movement as well as to the more theatrical British punk acts of the late seventies.

Releasing music through their own Alternative Tentacles label, the Dead Kennedys established their satirical identity with the striking titles of their first three singles: “California Über Alles” (1979), “Holiday in Cambodia” (1980), and “Kill the Poor” (1980). “I am Governor Jerry Brown,” proclaims Biafra in the opening line of “California Über Alles.” In character, he then ventures into a fantastical Orwellian vision of a future hippy dictatorship where “zen fascists” dose the masses with “organic poison gas.” Besides its primary political purpose, the song also alludes to the ubiquitous religious cults dotted around California in the 1970s. Biafra envisions a small leap from their communal mindset to an authoritarian state overseen by “the suede denim secret police.”8 The follow-up, “Holiday in Cambodia,” became the band’s signature song, though its four-plus-minute length, mid-paced tempo, and echoing guitars make it an anomaly of California hardcore. With a hat-tip to the Sex Pistols’ “Holidays in the Sun” (1977), Biafra employs Johnny Rotten’s “what if . . . ?” approach to his fantasy satire. What if the rich white kids who claim to be “down” with the poor black underclass were transported from their comfort zones to the rice fields of Pol Pot’s Cambodia? Like Kurt Vonnegut, Biafra uses imaginative leaps in order to make sardonic social comments. Here, the targets are the so-called “yuppies” and “wiggers” that would become topics of talk shows over the next two decades. Like the best satirists, DK were prescient as well as pointed.

Single three saw the band return to the speaker-parody mode. “Kill the Poor” is essentially an adaptation of Jonathan Swift’s famous “A Modest Proposal” (1729) essay, in which he ironically suggested that the most practical way to solve the starvation problem in Ireland was to eat the children. Biafra calls for similar “efficiency and progress” in eradicating the poverty and unemployment problems of the United States. As the neutron bomb does no collateral damage to property, the speaker-as-politician declares, “Jobless millions whisked away. / At last we have more room to play. / All systems go to kill the poor tonight.”

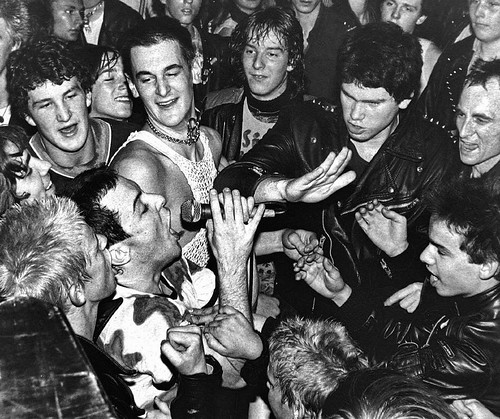

And if these singles (and their album Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables [1980]) were not controversial enough, the band followed them up with “Too Drunk to Fuck” (1981) and “Nazi Punks Fuck Off !” (1981). While the former speaks for itself, the latter saw Biafra turning his attentions away from macro political concerns to the escalating violence within the California hardcore scene. By the turn of the decade, a more aggressive “meathead” fraternity had taken over punk crowds, and a disturbing neo-Nazi element was among them. In no uncertain terms, the band eschewed their usually comedic approach, telling this faction “Stab your backs when you trash our halls / Trash a bank if you got real balls.”

The controversy surrounding DK’s output finally caught up to them with the release of Frankenchrist in 1985. The band was a regular adversary of the PMRC as they grew emboldened in the early 1980s, and their inclusion of an H. R. Giger poster illustration (the so-called “Penis Landscape”) with this album gave the censor-mongers something to act on. Biafra was charged with distribution of harmful material to minors, the lengthy trial ending in 1987 with a hung jury. Embittered by what were becoming daily infringements upon his freedom of speech and equally disturbed by authorities’ unwillingness (or inability) to recognize the band’s satire and parody at play, Biafra lurched into a Lenny Bruce–like downward spiral and siege mentality. Though internal disputes were factors, too, the Dead Kennedys were laid to rest with their aptly titled 1986 finale, Bedtime for Democracy.

as they grew emboldened in the early 1980s, and their inclusion of an H. R. Giger poster illustration (the so-called “Penis Landscape”) with this album gave the censor-mongers something to act on. Biafra was charged with distribution of harmful material to minors, the lengthy trial ending in 1987 with a hung jury. Embittered by what were becoming daily infringements upon his freedom of speech and equally disturbed by authorities’ unwillingness (or inability) to recognize the band’s satire and parody at play, Biafra lurched into a Lenny Bruce–like downward spiral and siege mentality. Though internal disputes were factors, too, the Dead Kennedys were laid to rest with their aptly titled 1986 finale, Bedtime for Democracy.

Internal fighting has kept both Jello Biafra and the re-formed Dead Kennedys (minus Jello) in the courthouse over the last two decades. Nevertheless, Biafra has continued to ply his satirical trade on the lecture circuit, lashing out at all who would compromise freedom of speech and expression. His perennial targets, the religious right and two-faced politicians, continue to fuel his righteous contempt and anger as he rages into middle age. Indeed, as a candidate for the Green Party in 2000, Biafra sought to infiltrate the political arena, voicing the same slogan he had once used when standing as a San Francisco mayoral candidate in 1979: “There’s always room for Jello.” It’s a modest proposal that fans of his firebrand form of subversive humor certainly second.

***

See Also: Rebels Wit Attitude at Softskull Press

See Also: The Only Band That Mattered

One response

Long live Jello! This indeed always room for Jello, Fuckers

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment, or log in if you’re already a paid subscriber.