Prior to launching The Rumpus, during our test phase, we ran this incredible, thorough, and thoughtful review of Roberto Bolano’s 2666 by Michael Berger. Today seemed like a good day to bring it back. – SE

Four years ago, I came up with an idea for my first novel after reading Charles Bowden’s Juárez: Laboratory of The Future, a hair-raising chronicle of the American journalist’s experiences in the Mexican border city of Ciudad Juárez. Bowden’s gritty tales of cardboard slums, malnourished rag-pickers and narco executions, all accompanied by photographs of murdered men and women, were impossible to forget. With savage grace, he lays bare the grisly mechanisms of a city notorious for drug-cartel violence, grinding poverty, rampant political and police corruption, and the largely unsolved sexual homicides of hundreds of women, most of them poorly paid factory workers. As with the photographs, Bowden’s furious, poetic words seemed to both denounce and exalt the paradoxes that make the city so fascinating. The more I read about the city, the more my conviction grew: I would one day write a novel about Juárez.

I was aware of the immense, even ludicrous challenges I had set for myself as a young, unpublished writer who doesn’t speak Spanish. But I was convinced that writers, even unpublished ones, should dream on large, improbable canvasses, if only for the thrill of risk-taking. Fortunately for me, the late Chilean au thor Roberto Bolaño beat me to it.

thor Roberto Bolaño beat me to it.

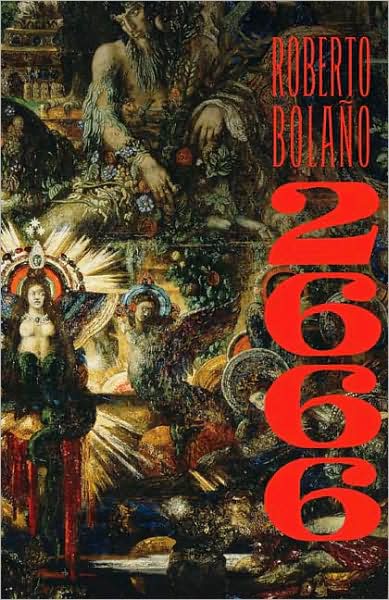

Not only is the posthumously published, nine-hundred-page, relentlessly brutal and apocalyptic 2666, which came out in November in a wonderful English translation by Natasha Wimmer, the great Juárez novel I dreamed about, but it is one of the great “everything” novels that a writer fantasizes about someday having the fortitude to pull off.

This five-part mega-novel has as its thematic centerpiece the sexual crimes against women in the city he calls Santa Theresa. But like some crazed resonance chamber, this notion of desire gone berserk enters into many asides – some unforgettable, some tedious – including modern German literature, Russian science fiction, the Black Panthers, the history of Chile, Dracula’s castle, Swiss insane asylums, the Aztecs, and Romania and Prussia in World War II. 2666 is structured as a polyphonic clash of voices and dreams, all trying to make sense of the insensible. Many of the novel’s characters succumb to murder, rape, torture, imprisonment, suicide, madness, disease, or war.

Lauded by everyone from The New York Times to TIME as one of the best books of 2008, 2666 is also one of the bleakest meditations on desire and history one would ever hope to read. But for patient readers who can distinguish human outrage from gory spectacle, who can savor long, intricate sentences and gorgeously weird tangents and who long to be reminded of how art, more than anything else, can make sense of humanity’s collective psychoses, I can’t recommend it highly enough.

Bolaño was dying of liver disease as he scrambled to finish 2666. The twilight of his life was spent fashioning the novelistic monster that would eclipse his previous works. According to Marcela Valdes, Bolaño researched the crimes against women in Juárez as if his life depended on it, though without being able to go there in person. No greater passion consumed him in the last years of his life. Why would a dying man choose to undertake a project whose resonating motif is the savage rape and murder of hundreds of women? The sheer audacity of the novel is that it reads at times as the ultimate indictment of Bolaño’s gender, his own dreams and desires, and especially the culture of machismo, gangsterism, and tyranny that passes for masculinity in many parts of the world.

When I first read about the murders in Bowden’s Juárez, murders that were part of a larger network of violence and corruption and that also involved American industry, I found it implausible that more people weren’t writing about these atrocities. The question was how to summon that kind of courage. I had no idea how a fiction writer could conceptualize such horrors on an artistic scale until I read 2666. Atrocities, however, are hardly alien to Bolaño’s work – as Valdes asserts, the great themes of his career are “the relationship between art and infamy, craft and crime, the writer and the totalitarian state.” In 2666, the specter that haunts the pages is Two-Faced Desire, an awesome, often irrational parasite that embodies love and communion on one hand as well as the potential, in every one of us, to maim, rape, and murder.

In the beginning, the book seems to be about four romantically entwined literary critics who are searching for their idol, the reclusive writer Benno Von Archimboldi, but even in the earliest pages hints of encroaching derangement and unreality abound. “Madness is contagious,” as the widowed professor Amalfitano declares while recollecting his wife’s mental illness and, at the same time, contemplating the paternal yet homophobic voice in his own head that convinces him he’s going crazy.

In the beginning, the book seems to be about four romantically entwined literary critics who are searching for their idol, the reclusive writer Benno Von Archimboldi, but even in the earliest pages hints of encroaching derangement and unreality abound. “Madness is contagious,” as the widowed professor Amalfitano declares while recollecting his wife’s mental illness and, at the same time, contemplating the paternal yet homophobic voice in his own head that convinces him he’s going crazy.

What’s at stake, established within the first thirty pages, is how quickly desire shape-shifts and turns feral if enough pressure is applied. The pressure can be anything, poverty or insecurity or madness or imminent death. Or simply the sense of impunity that comes with power. The man laughing in the bar at night becomes, by day, the pig-masked child rapist in the black van with tinted windows. The virile Romanian general is stripped naked and crucified by his own men. Two docile academics are reduced to beating a Pakistani cab driver almost to death. Russian Jews are murdered by their former comrades, or else rounded up by the Germans. An artist cuts off his hand for money; a man kills his wife out of love. The devotion to art and literature becomes secondary to the hunger for money, sex, revenge, and personal validation. Bolaño sums up his novel’s mordantly comic cynicism in Part Two, where Professor Amalfitano argues with the voice in his head: “So everything lets us down, including curiosity and honesty and what we love best. Yes, said the voice, but cheer up, it’s fun in the end.” And, actually, it is.

Perhaps a dying man who lived under two repressive regimes as a radical outlaw poet is indeed the best chronicler of the hysteria of male desire. In 2666 Bolaño stirs up the depths of our worst nightmares as well as shatters the facades of our waking dreams. Nobody in Santa Theresa knows what’s worse: the violence that can’t be explained except as the work of an unknown serial killer with a penchant for biting off women’s nipples, or the “normal” violence that occurs when a man, bloated with drink and hearsay, shoots his wife in the head inside a busy nightclub.

But in 2666 nothing is normal. Banality is outrage; atrocity becomes the average. The characters navigate blindly through dark fields, twisting alleys, perilous ravines, and the passageways of ruined castles. What’s left at the end is the lingering image of a dark, unlit street that seems to disgorge mutilated bodies and swallow up perpetrators like dust. Cloaked in the deadpan poetry of Bolaño’s prose, this horrific world becomes almost too much to bear.

Devotion to such a sprawling fugue on human depravity takes an emotional toll, or at least it should. It took me two months of slow reading, usually at home in bed or on the morning commute, to finish 2666; midway through, deep into the harrowing forensic reports in “The Part About the Crimes,” I started having nightmares. Mostly they were anxiety dreams, either about the emptiness of my own creative efforts or my shortcomings as a man, both sexually and emotionally. Sometimes they were worse.

At one point, I stumbled upon an online article by Nicholas Kristof in The New York Times entitled “Terrorism That’s Personal”. With no warning, the link sent me directly to a photograph of a woman with a burned, mutilated face, followed by Kristof’s exposé on acid attacks in Cambodia and Afghanistan.

At one point, I stumbled upon an online article by Nicholas Kristof in The New York Times entitled “Terrorism That’s Personal”. With no warning, the link sent me directly to a photograph of a woman with a burned, mutilated face, followed by Kristof’s exposé on acid attacks in Cambodia and Afghanistan. ![]() The woman in the picture wanted to divorce her husband, so he poured hydrochloric acid on her face, a common and rarely prosecuted practice in certain countries. I started dreaming this woman was in my room, watching me. Sometimes she was one of Juárez’s femicide victims. Sometimes she was one of the women of Guatemala, another under-reported nightmare I discovered online.

The woman in the picture wanted to divorce her husband, so he poured hydrochloric acid on her face, a common and rarely prosecuted practice in certain countries. I started dreaming this woman was in my room, watching me. Sometimes she was one of Juárez’s femicide victims. Sometimes she was one of the women of Guatemala, another under-reported nightmare I discovered online.

As I waded through 2666 and related news articles, I grew convinced that the war against women is a perpetual, global enterprise with ancient and inextricably deep roots. I had no clue what to do with these findings. I certainly didn’t sleep any better. I just kept reading, hoping 2666 would provide solace, while knowing very well that it wouldn’t.

Even if you have read the countless, gushing reviews of 2666 by everyone from Jonathan Lethem to Sarah Kerr, it is hard to prepare yourself for the novel’s occasionally gut-wrenching scenes. Maybe you glossed over the part in the review that explains that the heart of the novel is a three hundred-page sex-crime narrative, much of which is written like a forensic report (“anally and vaginally raped” becomes a stomach-turning refrain). Bolaño’s meticulous rendering of the crimes, depictions that stem from the Mexico City reporter Sergio Gonzalez’s actual investigations in Juárez, are told in a neutral, matter-of-fact style that serves to humanize the victims. We learn about their families, their boyfriends, and their plans for the future that will now never manifest. Even the suspected murderers are given illuminating backstories. A reader can’t be blamed for wishing Bolaño had shown occasional restraint, as in the case of the autopsy of an eleven-year old girl who had been anally and vaginally raped and “died of a heart attack while being subjected to the abuses described above.”

“The Part About The Crimes,” far from being just an overwhelming inventory of sexual homicides, is also a haunting tapestry of Mexican life interwoven with the lives of cynical detectives, charismatic seers, gay Mexican talk show hosts, church-desecrating vandals, beautiful asylum directors, Machiavellian female politicians, ruthless drug lords, rookie cops, monstrous prisoners, Marxist priests, and one towering German ex-pat who might be guilty or might not be. “The Part About The Crimes” is the novel’s highlight, a brilliantly paced, action-packed noir that happens to be the grisliest and longest section. At times I wished it wasn’t crafted so expertly so that I didn’t have to keep confronting the worst that humans have to offer.

I wonder again, even though maybe I shouldn’t, about the dying man behind the book and his own notions of responsibility. I find interesting that the only rapes in 2666 that are described as they unfold are the male-on-male rapes in the Santa Theresa prison. In these scenes, you get a front-row seat as shivs are brandished and bodies are destroyed, all while the guards are watching. 2666 leaves it to the reader to decide what entails nobility and responsibility in a place as denuded of hope as Santa Theresa, or in the war-torn Eastern Europe that Archimboldi lives through, or even in the European literary conferences where critics are found hobnobbing through a haze of scorn and unreality.

I wonder again, even though maybe I shouldn’t, about the dying man behind the book and his own notions of responsibility. I find interesting that the only rapes in 2666 that are described as they unfold are the male-on-male rapes in the Santa Theresa prison. In these scenes, you get a front-row seat as shivs are brandished and bodies are destroyed, all while the guards are watching. 2666 leaves it to the reader to decide what entails nobility and responsibility in a place as denuded of hope as Santa Theresa, or in the war-torn Eastern Europe that Archimboldi lives through, or even in the European literary conferences where critics are found hobnobbing through a haze of scorn and unreality.

History, in this book, is unfolded as a consequence of male fear. One of the many minor characters in part four, Elvira Campos, a mental asylum director, explains to her detective lover how all sorts of fears predominate in Mexico, but perhaps the most dominant ones are gynophobia (fear of women) and sacraphobia (fear of the sacred), leading one to suspect that these are one and the same.

In Part Five we live through the bureaucratic nightmare of a Polish civil servant who is ordered to dispose of an accidental shipment of 500 Jews or else violate direct orders. Eventually he makes others – policeman, firemen, street children – do the work for him. This scene has all too obvious resonance with the liquidation of women in Santa Theresa – and the bureaucratic fears that stifle any attempt to halt the barbarism.

So if there are no answers at the end of 2666, is there at least some faint glimmer of light? Can any reader withstand a 900-page atrocity exhibition, in which unchecked evil always wins, without some consolation prize? Bolaño’s answers to these questions are more like bittersweet love letters to literature and desire. Or sex and writing if you will. At the very least, he implies, these pastimes will keep you pleasantly occupied while the world keeps ruining itself. But whatever writing or lovemaking you attempt it must always be on the edge of some yawning abyss. These acts must be thought of as both necessary to your survival and most likely the last things you do before being crushed by the boot-heel of History – as they are for the lovers in “The Part About Archimboldi,” living under the ominous specters of Hitler and Stalin and the death camps and the Great Purge, who are said to “have fucked as if they had only a few hours left to live.”

Here we have writers and revolutionaries, betrayed by their deepest hopes and condemned to die at the hands of their former friends, fucking each other madly, “as if once the nakedness of the slaughterhouse had been achieved everything else was unacceptable theatricality.” Living under the duress that History imposes allows for a playful, violent sensuality that gives birth to great love affairs and great books, often simultaneously. This is the secret that Bolaño dispenses at the end of 2666, but not without a sorrowful sigh.

In one of the extremely rare “bad” reviews, John Lingan laments that the consensual sex in the book (which is ample) is always more “like an altercation” and thus not at all different from the novel’s countless rapes. I think he misses the point. Bolaño’s fictional lovers are gifted with inhuman stamina and intensity, as well as with the unruly, ambiguous desires of artists, soldiers, and drifters. Funny enough, in the pages of 2666 as in our own world, those in power, like the drug lords and warlords, the generals and police chiefs, also entertain desires that aren’t so different from those of the powerless – except that they can express those desires with impunity. Given the right conditions, everyone is a potential perpetrator.

The novel’s final section, although set in the chaos of World War II, is a surreal, tragicomic odyssey in which war becomes secondary to the plights of dissidents, writers, publishers, artists, and intellectual exiles. Although there were hints earlier (the black journalist Oscar Fate’s journey in Part Two, for example), it is in the finale that the notion of the writer-as-doomed-hero is etched most vividly. Here we come to know the lives and loves of the Prussian libertine-turned-publisher, Baroness Von Zumpe, the Jewish intellectual Ansky, the condemned science fiction writer Ivanov, and most movingly, Benno von Archimboldi, the writer-hero of the novel, a giant of a man who lives as if submerged underwater. Archimboldi is Bolaño’s ironic archetype of the worldly writer: a soldier who drifts through endless war as if entranced but then turns violently against the barbaric ideology of his homeland; a hardened, yet scrupulous man who loves unreservedly despite disease and madness; a reclusive writer contemptuous of fame who isn’t afraid, for example, to write a novel about seaweed.

Although there are elements of the idiot, the cynic, and the naïf to Archimboldi, his unusual heroism lies in his tenacious ability to look beyond the horrors of our century and find a wounded, yet redemptive beauty amidst the ruins. The writer, for Bolaño, is just this partly idiotic and partly sainted creature who can stare meaninglessness in the face and still produce meaning. In “The Part About Archimboldi,” Bolaño’s famed “logic of dispersion” reaches a fever pitch and the book effuses at length about everything imaginable (some of the allusions are explained in the translator’s fascinating Notes For An Annotation of 2666. The novel is finally cyclical, beginning and ending with the howling desert. Yet despite this unremitting despair, a vivifying, promiscuous sense of life shines through. It is life that is forever straddling the void but not without a certain, hopeless caress.

**

See Also: 15,000 Pages In Three Minutes

See Also: Lost and Found by Steve Almond

4 responses

This review was beautifully crafted. The final two sentences burned a hole through me– it was both tantalizing and foreboding.

I hope to read more from Mr. Berger soon.

I am mid-way through Book Four, and it has been a real pleasure to spend time with Bolano through the Michael Jackson spectacle (here in LA), summer heat, political controversies, and more news of police “miscommunication.” I haven’t had any nightmares, either.

I read 2666 last year (2009) and I knew when I finished it I would need to reread it. Somewhat daunting thought…so I have been reading reviews since to

assist me in attempting to understnd the work better. I have read several reviews and this is by far the best I have read.

Thank you, Mr. Berger for crystallizing some seemingly (to me) disparate elements of the narrative into a thematic perspective

the violence did not affect my sleep. It is because of that straightforward manner in which killings are written and how the whole novel is written.there is so much going on and of these details weave through the whole in interconnecting strands. There is this rhythm to the language as well, which really captured me. Enjoyed the review but think you should write your book

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment, or log in if you’re already a paid subscriber.