The New York Times reports that memoirist and biographer James Lord died of a heart attack this week at the age of 86. And this moves me, because while there are The Last Book(s) I Loved, there are also those Books I Have Always Loved, among them A Giacometti Portrait, written by Lord in 1965.

The New York Times reports that memoirist and biographer James Lord died of a heart attack this week at the age of 86. And this moves me, because while there are The Last Book(s) I Loved, there are also those Books I Have Always Loved, among them A Giacometti Portrait, written by Lord in 1965.

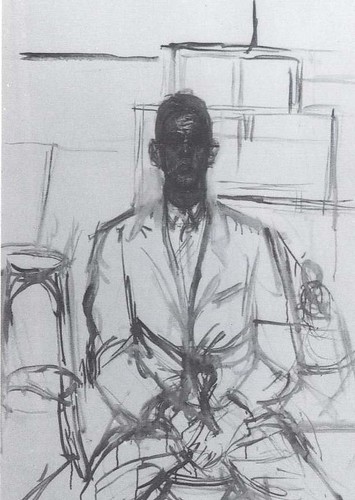

Lord was Alberto Giacometti’s subject for a painting, sitting for an initial session that turned obsessively into eighteen sessions. He recorded in eighteen corresponding chapters, and just 117 pages, the details of the artist’s method, his tormented struggle to create, their conversations and the experience of the subject himself—his anticipation, disappointment, curiosity and, at times, exhaustion.

Giacometti’s effort centered primarily on Lord’s face and head, though almost his entire body is portrayed. Each session began with the destruction of the previous day’s efforts, with Giacometti not just obliterating the painted head of his subject, but feeling that it was “necessary to start his entire career over again every day, as it were, from scratch.” Because each day was different—for better or worse—Lord captured how Giacometti lived almost completely in the moment when his brush was against the canvas.

“What meant something, what alone existed with a life of its own was his indefatigable, interminable struggle via the act of painting to express in visual terms a perception of reality that had happened to coincide momentarily with my head. … But he was committed, he was, in fact condemned to the attempt, which at times seemed rather like the task of Sisyphus.”

When I read the book, I was studying philosophy and fine arts in college, and systematically replacing the religion of my childhood with relentless existentialism. My paperback copy is bent and loved. Fanning through the pages plays a strobe of yellow highlighting. There are snippets of conversation that I adored (“Hell is right there.” “Where,” I asked. “On the tip of my nose?” “No. It’s your whole face.”) and passages of Lord’s observation that were poetry (“Through his finger as it moved, his entire being seemed to flow from him into the ideal void where reality, untouched and unknown, is always waiting to be discovered.”). But as a whole, the book demonstrated what it meant to live as an existentialist, an artist and a writer, how to ride an almost continuously breaking wave of creativity and passion into a wall of complete demolition—in both life and human relationships–and emerge with something beautiful.

When I read the book, I was studying philosophy and fine arts in college, and systematically replacing the religion of my childhood with relentless existentialism. My paperback copy is bent and loved. Fanning through the pages plays a strobe of yellow highlighting. There are snippets of conversation that I adored (“Hell is right there.” “Where,” I asked. “On the tip of my nose?” “No. It’s your whole face.”) and passages of Lord’s observation that were poetry (“Through his finger as it moved, his entire being seemed to flow from him into the ideal void where reality, untouched and unknown, is always waiting to be discovered.”). But as a whole, the book demonstrated what it meant to live as an existentialist, an artist and a writer, how to ride an almost continuously breaking wave of creativity and passion into a wall of complete demolition—in both life and human relationships–and emerge with something beautiful.

Lord exposed how much destruction was necessary—at least for Giacometti—to the process of creation. He also captured the complexity of the relationship between artist and subject:

“There were elements of the sadomasochistic in our relationship. At moments it seemed difficult to determine which one of us was responsible for the aura of anxiety that surrounded our mutual work in progress. I as the model, though a fortuitous element, was nevertheless one without which the work could not proceed. Consequently, it was sometimes easy to confuse my appearance with my person as a source of dismay. On the other hand, if he could not work without me, the painting could not exist without him. He had absolute control over it, and by extension—taking into account its nature, my admiration for him, my desire to possess the finished product, and the fact that I was remaining in Paris only to pose—control over me, too. The painting seemed at times to exist both physically and imaginatively between us as a bond and a barrier at once. However, in a situation of which the ramifications were inevitably complex, not to say ambiguous, it would have been difficult to determine exactly what acts were sadistic and/or masochistic on whose side and why.”

The portrait is shown in each stage of its evolution at the beginning of each chapter—more or less light, intensity, expression. The rest of Lord’s body seems almost irrelevant. And by the end of the book, the image that Giacometti finally settles on seems due, more than anything, to time running out. The portrait-in-process had been like a shadow that fell from the painter and painted at once, changing with every gesture—an entirely fluid likeness that should, to be true, go on changing indefinitely.

When Lord finally announced that he had to leave for the United States, Giacometti was frustrated. Yet it was the only relief in sight for both of them, defining a clear end to their sessions. They had captured each other, on canvas, in words, outsmarting temporarily that dark solitude and inevitable void that each so clearly espoused. Undoubtedly it was the reverence for that end that gave both author and artist their fuel.

One response

Love this:

Each session began with the destruction of the previous day’s efforts, with Giacometti not just obliterating the painted head of his subject, but feeling that it was “necessary to start his entire career over again every day, as it were, from scratch.†Because each day was different—for better or worse—Lord captured how Giacometti lived almost completely in the moment when his brush was against the canvas.

Tomorrow morning I will cobble together a new pair of shoes, head to Green Apple, and buy this book.

Thank you!

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment, or log in if you’re already a paid subscriber.