Robert Hass, Bush’s War, and the death of a father

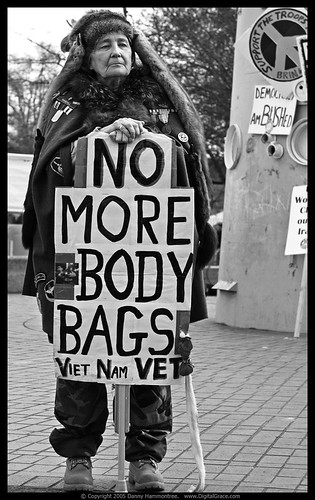

illustration by Marianne Goldin

criminals with priests’ black benedictions

came by sky to kill children

and in the streets the blood of the children

ran simply, like children’s blood.

—Pablo Neruda, from “I am explaining a few things.”

In the waiting room, reading Robert Hass’s, Time and Materials (2007) I began thinking of Hass, the gray haired man, an intelligent and sensitive man—that is the impression I have from the poems (and the jacket photo)—and trailed off to memories of my father, because that is how my thinking goes sometimes, not disciplined, but loose and gangly, and maybe because they both seemed like good men, cut from similar cloth, having all the right intentions, maybe because there comes a time when a son must reconcile with his father. My father did his post-doctoral work on the West Coast, at Berkeley, several years before Hass would go to Stanford to pursue literature. My father became a scientist—a biochemist and chemist, and later worked with computers, early on when computers filled rooms and then later when he carried one, as he said, “powerful enough to run a small nation,” from his office at Cornell Medical to his apartment building across the street, intern housing where he lived all his life—because he believed that science would change the world.

My father prided himself on his philosophical detachment and empiricism. He also was alcoholic, and at his bar stool at Finnegan’s Wake on 73rd and 1st Avenue, he would brag that his corner was the “liberal corner,” while drinking his “RudyMary” (more horseradish, more Tabasco). His bar buddies were a tide of conservatism and he was the bulwark—their drunken companionship always more potent than politics. When we’d meet there and take a table in a corner to eat bangers and mash, he might say, When I become president of the world. . . and there would be this or that or some other thing, how science would solve all our problems. And he was right. Damn right! His world would be a better place. But my father’s liberalism—while it always made sense, was always so reasonable—never changed anyone’s mind in that bar or anywhere else. When he died, I went into that bar and had a Guinness in my father’s honor—my wake in Finnegan’s Wake. What his bar buddies said of him: “Your dad never said a bad word about anybody.” My father believed that everyone, all at once, might suddenly and in concert see the truth of reason.

Hass, a decent and intelligent man, a man privileged and aesthetically self-satisfied, also wants to do good. In Time and Materials, he sometimes pointedly turns away from image making, abandoning the poetic acts of attention, which compress time and enrich life, in order to address a world of generalities, and tries to make sense of a world that seems to have gone mad.

Hass challenges the reader even in the title of “A Poem,” a poem which itself is prosaic, generalized, abstract; it relays fact and figures, tells us, for example, that “In the first twenty years of the twentieth century 90 percent of war deaths were the deaths of combatants. In the last twenty years of the twentieth century 90 percent of war deaths were deaths of civilians.” There is no music in this language, and I guess Hass’s point is there shouldn’t always be music. A clue, earlier in the collection, Hass writes, “It is good sometimes for poetry to disenchant us.” Charm, poetry, beauty in language are a masquerade, a complicity in the face of serious issues—war, death, the wresting of life from the innocent, done in our name, and in the name of what we believe in.

In “Bush’s War,” Hass writes

Or the raw white of the exposed bones

In the bodies of their men or their children

Are being given the gift of freedom

Which is the virtue of the injured us.

It is hard to say which is worse, the moral

Sloth of it or the intellectual disgrace.

Hass draws our attention to good sense, pointing out our ridiculous and faulty reasoning. And I say, yes, we do have “moral sloth.” We have “intellectual disgrace.” I agree—very much so. You are right! I see his good sense and I see his good intentions, but, like my father’s pronouncements from his corner in Finnegan’s Wake, I see the impotence of the act. Reason is not longer a convincing argument. We don’t live in an age of reason.

In “The Second Coming,” Yeats, wrote that the best “lacked conviction while the worst were full of passionate intensity.” WWI, “the war to end all war” was anarchy “loosed upon the world.” And wasn’t Yeats right? Didn’t he hit the nail right on the head? Dead in 1939, Yeats could not have foreseen history as it unfolded, and what a history. His nail-square-on-the-head poem, one of the best, most incisive anti-war poems of all time, yielded nothing, no change in the future, no end of war—same today as it was in 1917, if not worse.

In “The Second Coming,” Yeats, wrote that the best “lacked conviction while the worst were full of passionate intensity.” WWI, “the war to end all war” was anarchy “loosed upon the world.” And wasn’t Yeats right? Didn’t he hit the nail right on the head? Dead in 1939, Yeats could not have foreseen history as it unfolded, and what a history. His nail-square-on-the-head poem, one of the best, most incisive anti-war poems of all time, yielded nothing, no change in the future, no end of war—same today as it was in 1917, if not worse.

Advertising is the new poetry; mnemonic, it bombards us with the antithesis of reason. It plays upon our fears, hints at our impotence, threatens us with social exile, even as it advances its most incongruous message: products will make us happy. Let’s face it, we’ve returned to magical thinking. Reason doesn’t reign. We feel powerful when we sheepishly follow the herd. We make war for peace. We acquire debt to build wealth. We strive to be forever young. We drop smart bombs and depend on military intelligence. All along, our material impotence wrestles with the oxymoronic promise of materialistic happiness. The hawk is a handsaw. Unreason is the status quo.

In the early Greek Dionysian mystery rites, priests used poetry—metered language, easier to remember—to help a fearful populace traverse the unknowable underworld. Through empiricism and deduction, people understood that they would die, but wanting to deny reason, they created priests who would assure them that they would not. The priests recited incantations that would allow acolytes to walk a right path in the land of death, answer the gods correctly, and pass through to an everlasting life-after-death. By manipulating people’s fear of death, the priests solidified power, but it was the people who originated that power, elevating priests and designating potentates—for order, for safety, out of fear. If they paid the priest, in death they might continue to prosper. They would retain an egotistical identity in this hierarchical afterlife—a place where some got in and some didn’t. Along with false security, the people bought irrationality.

These mystery rites rose along with consciousness, from the ether, organically, and were an ingenious economic model. Irate customers never asked for their money back—couldn’t. And those who could afford a little extra dinero had their poetic, after-life directions hammered out on gold and buried with them. The gold, valuable because it wouldn’t tarnish over time, could be read even by the long dead—an after-life cheat sheet.* The elite could bank on one sure thing: people fear death. Those who could afford it willingly handed over their money and their reason in order to participate in the orgiastic rituals meant to simulate death, the Bacchanalia. And from accounts, this was a damn good time. Our modern consumacopia doesn’t seem nearly as much fun.

This universal fear of death and the establishment of a hierarchy based upon divisive notions of “us” (those who will live forever) and “them” (those who will not) has been the model for sustaining the high priests’ power always—for the Greeks, for the Romans, and now.

In “State of the Planet,” Hass draws our likeness to that of Rome, hoping perhaps for some necessary historical perspective:

They drained the marshes around Rome. Your people,

You know, were the ones who taught the world to love

Vast fields of grain, the power and the order of the green,

Then golden rows of it, spooled out almost endlessly.

Your poets, those in the generation after you,

Were the ones who praised the packed seed heads

And the vineyards and the olive groves and called them

“Smiling” fields. In the years since, we’ve gotten

Even better at relentless simplification, but it’s taken

Until our time for it to crowd out, savagely, the rest

Of life. No use to rail against our curiosity and greed.

They keep us awake. And are, for all their fury

And urgency, compatible with intelligent restraint.

He is right again—very massively right. His equation of agricultural plenty and the narrowing of mind is dead on, and the pursuit of “relentless simplification,” and the cooption of “intelligent restraint,” yes, right again. And that it was “love” not hate that led us here. He is right, but what good can it possibly do when reason itself falls short in an unreasonable world. In “Bush’s War,” Hass, wonders, “Is it that we like kissing and bombing together?” Perhaps—the juvenile psychology of sex in a graveyard—but Hass seems unable to grasp our oxymoronic quality. Caught in his world of reason, he cannot see that life and death are not distinct, and to talk of one without the other is a disjuncture, a lie of ourselves. What I mean is, we’re scared stupid. What I mean is, he doesn’t see we’re nuts.

Under the heading, “Horace: Three Imitations,” Hass writes in Odes, 3-2,

And say with a shudder: Pray God our boy

Doesn’t stir up that Roman animal

Whom a cruel rage for blood would drive

Straight to the middle of any slaughter

It is sweet, and fit, to die for one’s country,

The thing I want to tell Hass is, we know we are that cruel Roman animal. We know. We know the irony of “dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.” We know Horace advanced war like a propagandist. We know Wilfred Owen borrowed the line to illumine the fallacy of patriotism. We see that Hass alludes to them both—a line that contains its own contradiction—but what Hass does not see is the line’s implication of a grander, kaleidoscopic impotence of his own anti-war sentiment. The modernists knew—and Hass is one—that sense from a single perspective is at best subjective. Perspective is power. So, the cubist, to fracture power, to challenge fascism, fractured perspective, but look long and hard at a cubist painting and consider its oxymoronic quality. In the end, we view it from a single perspective, right? Now consider this failure in a masterpiece like Guernica. Guernica leaves us with a conflicted message: war might be horrible but power (Picasso’s, the art’s, the viewer’s) is good. The failure of Guernica is also Hass’s failure because antiwar poetry (and art) is always a failure—to call it a beautiful failure or a necessary one does not mitigate that failure. Keats thought beauty was truth, but we know that truth is perspective. Instead it seems that beauty is power and power beauty. How do you disparage the advancement of power in a line rendered powerfully? Confused, we remain unconvinced. Is war bad? It feels good to kick ass, right? Are cigarettes bad? They make us feel good. Should we not drink quite so much? I might just beat that hangover if I just keep at it, and isn’t that something? We are just not reasonable. We have internalized a state of oxymoronic imbalance, one of contradiction and roiling blood and heart and a thousand inarticulate tongues we don’t speak. But our problem is not nature.

The thing I want to tell Hass is, we know we are that cruel Roman animal. We know. We know the irony of “dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.” We know Horace advanced war like a propagandist. We know Wilfred Owen borrowed the line to illumine the fallacy of patriotism. We see that Hass alludes to them both—a line that contains its own contradiction—but what Hass does not see is the line’s implication of a grander, kaleidoscopic impotence of his own anti-war sentiment. The modernists knew—and Hass is one—that sense from a single perspective is at best subjective. Perspective is power. So, the cubist, to fracture power, to challenge fascism, fractured perspective, but look long and hard at a cubist painting and consider its oxymoronic quality. In the end, we view it from a single perspective, right? Now consider this failure in a masterpiece like Guernica. Guernica leaves us with a conflicted message: war might be horrible but power (Picasso’s, the art’s, the viewer’s) is good. The failure of Guernica is also Hass’s failure because antiwar poetry (and art) is always a failure—to call it a beautiful failure or a necessary one does not mitigate that failure. Keats thought beauty was truth, but we know that truth is perspective. Instead it seems that beauty is power and power beauty. How do you disparage the advancement of power in a line rendered powerfully? Confused, we remain unconvinced. Is war bad? It feels good to kick ass, right? Are cigarettes bad? They make us feel good. Should we not drink quite so much? I might just beat that hangover if I just keep at it, and isn’t that something? We are just not reasonable. We have internalized a state of oxymoronic imbalance, one of contradiction and roiling blood and heart and a thousand inarticulate tongues we don’t speak. But our problem is not nature.

Deadly interspecies conflict is rare in the natural world, even among predators. Tigers don’t kill each other. Lions don’t. Bears don’t. Posture, yes. Butt heads and horns and rear up, but kill, no—male bears do kill their young. Maybe that is something to think about—the male bear killing its young. It wouldn’t be too far off the mark to say it is all about sex, and that human violence is about sex, and that this is predominantly a masculine issue. In this men are the same as other species of male animals. We posture, fluff our mane, drive our Hummers, spit on the sidewalk—we vie for power to secure sex. Sure, our feelings of social powerlessness flame our fantasies of aggression. Still, we politely wait on line at the bank. We do not often kill each other. Killing is an expression of grave natural imbalance. But we, like the good soldier, accept the unreasonableness we are inundated with. We learn over and over again how inadequate we are without x and that we can kill y without compunction. There is zero sense to it. Both are blatantly false constructs. But this is what we believe, because being human means living in a state of unreality, divorced from nature. This is our sole identifying trait, and is it any wonder that we act so ruthlessly to keep our delusions alive even as they act against our own self-interest, against our own species and ourselves? We must not behave like animals. If only we did.

I never understood anything of my father’s science. I know he co-wrote a paper on “Electron Microscopy of the negatively stained and unstained fibrinogen”—whatever that is. I know he died thinking science would solve all of the world’s problems. He’ll be disappointed, I think—at least as long as Yeats, as long as Owens and Hass, as long as all those who believe in poetry or science, in reason and clarity—as long as all of these good men with their best intentions. He believed in science even though he saw the physics of Hiroshima, the chemistry of napalm, saw his beloved computers guide missiles in Iraq, witnessed, toward the end, laser-targeting systems and killer drones, called Predators. He would sit at Finnegan’s with his “RudyMary,” watch the news, and tell his pals what he would do, if he were President, how the world could be a better place, reasonable and just. Science, he’d say, could take care of the details—not in some far distant time, but now, right now, if we wanted it to—disease, hunger, material suffering of all kinds. There’d be zero population growth, if not negative population grown, euthanasia, and people could work less, 3 days a week, he thought, have more time to pursue the arts and cultivate their spirituality, and everyone would leave each other alone. Wasn’t that what we were striving for, greater equality and justice for everyone? When I was there, he told me these things too. And I weighed: science and poetry, science and poetry. He thought our capacity to understand a world outside of ourselves, to pursue a right path, this was what made us human. I thought, if only we truly felt each other as ourselves. My father died in time of war.

History has always moved in two contradictory trajectories: one advancing exploitative self-interest and the other egalitarianism. Our genetic impulse, according to the “selfish gene,” is one of genetic persistence and our complex social organization is a mating hierarchy. Our world is not unlike other complex social organisms—bees, ants (think of the worker and queen) herd animals or predatory dogs—the individual in large part subsumed by the advancement of the whole, a dispensable part sacrificed without compunction in service of the larger collective organism, whose impulses and destiny are not comprehensible to the individual parts. We might rile against this, but so we are—accomplice to some destiny driven by our genes and beyond our comprehension. And in the big picture we know species surge and decline. We are part of a larger system. In general, for us, so far, so good. It’s been surge. Though we’d very much like to last, in the end, that won’t be possible.

For all our momentary and individual charms, for all our intellectual good sense, as a species we are a social organism directed by base instincts, exacerbated and amplified by a larger dynamic organism, all the more pernicious for not being organic. This larger system functions at the insistence of sun and rain, in the movement of the planets, in the dissipation of the universe. It is not rational. Nor is it irrational. Its impulse reflects the individual impulse even as it drives that impulse. Both the social organism and the individual organism want to survive, only the social organism lacks a consciousness and a conscience. Perhaps it is economy. Perhaps it is something else. We are its cells and digestive enzymes. Other than that, it is just like us. It wants. It has the urge to surge. Stupid and afraid, it is a rudimentary organism driven by the same impulses that will inevitably destroy it. Born out of instinct and evolving a conscious intellect, individually we can imagine our own death—we believe this makes us unique in the animal world, but this is not so—our brief moment of flux, the force of life towards death, is the same bloom of life in everything—animate and inanimate, an impulse thrust upon us in the wake of an expanding universe—in a mystery of physics.

And isn’t this also the originating impulse of poetry? Our own poetry—not so different than the bird’s song or the patterns of wood worms under bark, the textures of igneous rock, helping us negotiate our commingled desire for life and fear of death—developing in us and gaining force along with our use of language, our consciousness. It is overwhelming—the bittersweet irrationality of our temporariness. It simply shouldn’t be, but it is.

To think of life as precious is commonplace, but that is what I do believe—the time of it, the verb of being, each beat of it, second and millisecond, more valuable than cars or houses. There is no greater crime against another than taking that time away. I am sickened by it, sickened by the people who engage in death for their profit, to advance their self-interest—even though they might pursue their aims out of fear, because they love the color of grass in fall, like me, want to live, and fear death. I cannot abide them.

War and poetry negotiate the same path, but war is the antithesis of poetry. War cheapens life—boys or girls, women and men, in the factory, in a field, at a wedding, drawing, considering dreams, ambitious for possibility, filled with jealousy and sometimes despair—obliterating our precious time. War is logistically efficient and reductively statistical. War is fought on the allure of the “higher good.” In poetry, the act of attention is the compression of time, the most valuable thing we have. For poetry, the “higher good” is the enemy.

War and poetry negotiate the same path, but war is the antithesis of poetry. War cheapens life—boys or girls, women and men, in the factory, in a field, at a wedding, drawing, considering dreams, ambitious for possibility, filled with jealousy and sometimes despair—obliterating our precious time. War is logistically efficient and reductively statistical. War is fought on the allure of the “higher good.” In poetry, the act of attention is the compression of time, the most valuable thing we have. For poetry, the “higher good” is the enemy.

Just before the spring of the Bush War, I saw my father for the last time. I was on my way to Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris to live for a year and write. He’d already had a lung removed and suffered a stroke, which left his speech impaired. He shuffled along, trouble with his left side. A lifetime of smoking and drinking undid him. I think my father knew he would not see me again. He died in the first summer of that war.

That last time I saw him, we went down the elevator to have a cigarette together out on the patio of his building, overlooking York Avenue and the hospital where he would eventually die. He told me he was going to quit smoking and drinking too. I thought that was crazy. Keep smoking, I thought. It’s too late to change now. Let’s get a drink. I was going to Paris afterall. I was going to sit in cafes and drink strong coffee or sip Pernod and smoke my brains out. We finished our cigarettes and he lit another one, an Ultra-light, but I had to go. I told him so. I had a lot to do. Then he told me something he’d never said before. He told me he loved me.

It is hard to know what your liberal father means when he says he loves you out on the slate patio in front of the building he’s lived in for thirty-five years, my liberal father who wanted to abolish inheritance, wanted to give his money to the Native American College Fund and to the NAACP. Now, if I think about it, I think that liberal love is a dispersed and ethical love—for humanity, for equality, for social justice. It hopes for the future against its better judgment. It is reasonable. This was the love he was talking about, because how else could it have waited so long. I understand. Yes, I understand. Liberal love, because of its unstable, slightly volatile nature, drives us just so toward alcoholism, smoking, and other forms of hedonistic death. Liberal love, idealized and platonic, is not a ferocious thing that moves the blood. Measured and proportional, it verges on the misanthropic—because human beings, when we really look at them, are a bit more despicable than kind. Yes, liberal love is reasonable, intelligent, a tad self-conscious, it weighs and balances and makes sense. So, it is hard to know what to think, when, at the last minute, he says something like that.

My father’s love, even in the last moment we would ever see each other, was not the selfish passion of those ignorant, morally slothful fathers, Bush and Bush, of Cheneys who shoot their friends and friends who apologize for it, of those who know about loyalty, about a tribe that devours its young—other people’s young. My father’s love could never be like that. Profoundly ethical, he would never suggest anyone die for something he would not die for himself, let alone sacrifice a generation for a piece of pie. But his liberal love finally was no better for the world, because like the world, love is not reasonable.

Of course, now I think I should have turned back, hugged him, or come up with something to say. But I didn’t. I was confused—not the first time or the last time for that. I walked away. Not the last time for that either. And later when I thought about it, I didn’t think about love. Instead I thought about him trying to quit smoking. How ridiculous. Even at the end, he wanted to live. I thought, there’s no telling what we will think or do once we stare into the mystery.

I am afraid of death, but I’m also afraid to see the world a no better place—no “higher good” ever achieved. I am afraid like Hass and my father and all the liberal fathers before me, afraid of the inherent hopelessness of humankind. I am afraid. I feel the loss of myself everyday. In our modern age, modern “good” health, forbids this consideration, but I am sad that I am dying and can’t be happy about it, all that I’ll miss, and that may be the only true thing I have—this inexhaustible sadness for myself, and everyone, that I’ll miss the birds who also lose what is joyful only in its loss, that I’ll miss my family, that I’ll miss the woman outside her mosque, the man in the shade of a tree in the Zócalo with his little dog, a boy and his Coke. I wish I’d done more for my friends, and loved more—Zondie and our dog, and rabbits, and rocks, and worms, bears and tigers, and in Zondie, that second heartbeat, ours, inexplicable, that pounds 163 beats a minute.

**

* For more on these poetic cheat-sheets, see, Cole, Susan G., “Landscapes of Dionysos and Elysian Fields,” Greek Mysteries: The Archaeology and Ritual of Ancient Greek Secret Cults, edited by Michael B. Cosmopoulos. Routledge, London and New York: 2003 (193-217).

See Also: The Rumpus Interview With Malcolm Gladwell

Robert Hass illustration originally for the poetry foundation

9 responses

Hi. I am a long time reader. I wanted to say that I like your blog and the layout.

Peter Quinn

Actually, tigers do kill each other. A decades-long big-cat trainer friend of mine once told me that, in the wild, tigers form bonds with each other, and then kill each other. “They don’t only kill for food,†he said, “lots of times they kill for giggles.†Is Bush’s War a giggle? Or, more aptly, a smirk? My friend went on to say that this joy killing doesn’t make them bad it just means “we need to recognize it for what it is.†But to this day he has never told me what “it is.†Not a zoological or philosophical explanation. Nothing. So what is it? Is it “moral sloth†or “intellectual disgrace†as Haas writes in Bush’s War? Incidentally, do pro-war poems only reside in antiquity and antiwar poems in modernity? What of the others? Is Wordsworth a pro-peace poet? Is his “dance with the daffodils†in defiance of “the raw white of the exposed bones� Speaking (were we?) of denial, Beckerian ringtones chimed at several points in reading this post (by the way, Otis, thank you for this doubtless labor of love). Ernest Becker won the Pulitzer in 1974 for his basic premise in The Denial of Death that “human civilization is ultimately an elaborate, symbolic defense mechanism against the knowledge of our mortality, which in turn acts as the emotional and intellectual response to our basic survival mechanism.†Is war, then, a symbolic defense mechanism against thinking about our own death? Is Robert Gates actually the Secretary of Defense Mechanism? Will Barack Obama be able to tell the difference? If war is one manifestation of the denial of death hypothesis then is a lifetime of money accumulation an another? Are friends who spend all of their time accumulating money unconsciously filling sandbags with depreciated dollars not for reasons of flood control but for fear control? Would it have made any difference in your life (or his), Otis, if your scientist father had chosen to seek the sedative properties of the Bhagavad Gita instead of vodka? It sounds like your father had a lot more fun and genial companionship in his life than did Oppenheimer. Don’t be afraid of death, Otis. “One day we’ll all be rescued by death,†said Schopenhauer. Until your boat arrives, Otis, just keep tossing out that happy lifeline I see you extending to your beautiful daughter in the picture.

I’ll still contend that killing reflects a grave imbalance in human beings. For more on this, take a look at On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society, by Lt. Col. Grossman, one of the best books I’ve ever found on the subject. Written from a military standpoint and for the purpose of examining PTSD and troubling trends in our culture, the book is particularly valuable in debunking the myth of human bloodlust, particularly in war, and the reductive “fight or flight†model. The operable word in the title, of course, is “learning,†which suggest being taught. As for animal violence , everyone should read, “An Elephant Crack Up?†by Charles Siebert, with its profound implications on unnatural violence among animals. As for Tigers and “joy killing,†I’d really have to take a look at that. The “joy†part sounds like a human attribution, part of our myth of tigers, which reflects our myth of violence and ourselves. I highly doubt that tigers are sociopaths, and if they are, there is a reason. At the very least, we aren’t likely observing a large predator in the “wild†without the corrupting influence of human encroachment—sort of like, reality television isn’t really reality, or let’s hope though maybe now we’re talking about evolutionary psychology, in which case it doesn’t matter. It’s reality now. I don’t know. One thing I’m pretty sure of, though, is that one tiger doesn’t ask another to kill for him. Here we’re talking about the teleological suspension of the ethical. I don’t get it totally, still working on it, but worth taking a look at in Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling. But in all, I don’t know enough about tigers, true. I’d love to write a book about them—so someone give me that job. Thanks so much for your very thoughtful response to my work—many of you rhetorical questions illicit a silent yes from me. I was once fortunate enough to meet Jack Gilbert and he said he’d like to die “eaten by a tiger.†I think I understand that. We should aspire to cat food.

I haven’t read Grossman’s “On Killing†but went to Amazon and read the review blurb from Publishers Weekly which stated: “Grossman argues that the breakdown of American society, combined with the pervasive violence in the media and interactive video games, is conditioning our children to kill in a manner similar to the army’s conditioning of soldiers: ‘We are reaching that stage of desensitization at which the infliction of pain and suffering has become a source of entertainment: vicarious pleasure rather than revulsion. We are learning to kill, and we are learning to like it.’†The “vicarious pleasure†part jumped out at me because I just recently finished reading Freeman Dyson’s wonderful autobiography, “Disturbing the Universe,†in which he points out that “there must be a middle ground on which reasonable people can stand, a ground which allows killing in self-defense but forbids the purposeless massacre of innocents.†For those unfamiliar with Dyson, he is Professor Emeritus of Physics at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, and a theoretical physicist who worked with Oppenheimer, Richard Feynman and crunched numbers in the operations research section of the Royal Air Force Bomber Command (he created devastation scenarios in bombing proposals). Dyson says, “Bombers are bad. Fighter airplanes and anti-aircraft missiles are good. Tanks are bad. Anti-tank missiles are good. Submarines are bad. Anti-submarine technology is good. Nuclear weapons are bad. Radars and sonars are good. Inter-continental missiles are bad. Anti-ballistic missile systems are good.†From this, written thirty years ago, we can pretty much be certain a copy of Dyson’s book never found its way on the nightstands of Bush, Cheney, Wolfowitz or Perle. I ask, is the soldiers’ “desensitization of killing†still not the “giggle of the tiger?†Or is it something else?

Hello from an old friend, Otis. This is a wonderful, meaty, thought-provoking essay. The last few paragraphs are beautiful–in particular your definition of “liberal love.”

I’ll be seeing my old friend and professor Allen W. in a couple of months at a conference in Chattanooga. Weren’t you at UTK? Did you work with him there?

Thank you for your thoughtful essay. I am reading it and the subsequent comments while serving in Iraq. I have had an ongoing inner conversation about what brings people to kill one another, and your thoughts inspire me to think in different directions. I should point out that I am a surgeon, and thus my perspective of this war is not to witness the doing of violence but rather to witness the effects of violence. It is very different to see human suffering inflicted on purpose, as in war, than to see injuries that are the result of accident, even when negligence (ie drunk driving) is causative. One theme of Otis’s writing seems to be that despite reasonable despair at killing, we keep on killing each other. Thomas Molitor speaks of young people learning to like violence through media, but I would contend that vicarious glorifying of violence is not new. I have two young boys. In their upbringing, my wife and I continually struggle to temper their play acting of violence. If you do not allow them to have toy guns, they will make guns out of sticks or paper towel rolls; if you take these handmade guns away, they will shoot each other with their fingers. I would point out that boys since the beginning of time have play acted combat, and in times past, or in cultures other than our own, this play acting is encouraged, as preparation for their eventual ascention to become the agents of violence. We find this distasteful in our enlightened society. Certainly, daily life in mainstream America does not require inflicting violence on others for survival. We have a justice system to punish those who do violence, because it is disruptive to the pursuit of life, liberty, and property. We are loathe to admit it, but violence does seem to be part of human nature. Coping with the effects of witnessing violence and human suffering is really what we learn, I believe. Soldiers and doctors have a common reaction to horrible experiences–they laugh. We make jokes about things that are not funny. We compartmentalize, putting our experiences in a safe place in our mind. The science of psychology is filled with descriptions of defence mechanisms. They are considered adaptive and healthy, in that they allow us to go on and be productive human beings, and it is considered mental illness when we allow ourselves to be so affected by horrors we have experienced that we don’t function as we are expected to. I propose that there are some things we should not cope with, that we should not become accostomed to, that we should not be able to walk away from and continue living as if they did not happen. Perhaps we are doomed to continue being violent not because we are natural born killers, but because we are too good at defending our psyche against the terrible things people do to each other.

Hi my name is Virgil, Interestingly enough i see this as a very entertaining and beautiful essay. I am a 14 year old and was reflecting in the context of this essay and it had a very strong impact in my soul, and heart it depicted a very true and sad truth that we all have to share even though some may not accept it but we all live in a crappy age,corruption is everywhere we are practically destroying our mother(mother earth) and society still claims its rightfull govern over our lives. War is just one of the medias in which a truthfull dicussion is attained we can read our leaders by it. If they are capable or not even if they say the contrary they have to battle themselves before they battle the other. War will destroy us slowly rotting our hearts to the point where we wont even distinguish right from wrong and it saddens me that our hearts will die in the youth that is to come.

Proudly a Puertorican

Virgil J Davila

please if you understand otherwise please contact me at vj557@hotmail.com

id be happy to hear your thoughts and maybe even discuss about it.

A couple more good “reads” on this subject which helps us see things through the minds of those who find themselves administering final justice (I hate that phrase too) are, “Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101…” by Christopher Browning and “This Way To The Gas, Ladies And Gentlemen” by Tadeusz Borowski. In “Ordinary Men:” we see and understand how that could just as easily have been you and me in a foreign occupied country in WW2 standing behind crouched men, women and children and pulling the trigger sending a fatal bullet into the backs of their heads without really being coerced with threats or punishments. In “This Way To The Gas, Ladies And Gentlemen” well, just re-read that title again. It says it all doesn’t it? Through books like these and poems and writing from the likes of Wilfred Owen, Siegfied Sassoon and Vera Brittain we do get a picture of what war does to people but unfortunately it all too often falls on deaf ears. It seems there’ll always be a significant percentage of the population who can easily be convinced that a war is just and necessary. It’s a political thing. Pity.

On the value of anti-war poetry, novels and paintings and some thoughts on what we refer to as “The Common Good.” In the animal world every part of a group (of ants, termites etc.)engages in actions that pretty much always have a positive benefitial affect on the group as a whole. If they didn’t they’d have been long extinct or even more to the point, never would have evolved in the first place. We humans are different. Sometimes our leaders genuinely have the common good in mind (Franklin Delano Roosevelt or Ghandi for example) in their decision making processes and sometimes it’s just the opposite, they only want to fill their own pockets and the “Common Good” be damned. I don’t think I need to point out a recent example of a 2 term president for that one. History is full of anti war poetry, novels and paintings and some who embrace these are disheartened that it’s all a futile exercise but I disagree. The cumulative affect of these great works are slowly, slowly becoming a tad more mainstream. Goodbye to the glorification of war movies with the likes of John Wayne leading the gallant charge against the Japs or Huns or yes even against the savage Indians and hello to anti-war movies and more realistic documentaries like Pacific by Tom Hanks. Even those old black and white WW2 documentaries which were sanitized back when I first watched them have now been replaced with ones which are much more graphic showing us how horrific war really is. Society is slowly coming to realize that war is not this wonderful glorious thing. It’s taken a while but this all started with the poets like Owen and Sassoon and writers like Vera Brittain. One thinks they went to their graves in despair with thoughts that all their works fell on deaf ears which on the whole it did but it sowed the seeds of knowledge and understanding and we’re just recently reaping the fruits of their labor. We’re not there yet but we’re slowly, ever so slowly getting there. We just need the present poets, writers and painters (and yes, song writers too) to keep up their good work.

So, thank you Otis Haschemeyer for your marvelous essay. It’s a feast of thoughts and ideas that will take me (and hopefully many others) a while to digest.

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment.