Grace Talusan reviews Masha Gessen’s fascinating but hard look at the decision to get a preventive mastectomy, in the context of Talusan’s own decision to get a preventive mastectomy.

A couple of years ago, as I decided whether or not to have a preventive mastectomy, a friend pointed me to a series of 2004 articles in Slate magazine by Masha Gessen. The author documents her decision-making process after learning she’d inherited the same genetic mutation that had caused her mother’s death at 49. Like me, Gessen carried the genetic mutation, BRCA1, one of two “breast cancer susceptibility” genes which confers a high risk of breast and ovarian cancers.

Gessen writes, “I did, I was told, have the option of getting out, or at least of sticking one foot permanently out the door, by getting all the potentially offending parts cut off before they went bad.”

This was before actress Christina Applegate made news by having a double mastectomy with reconstruction, after a breast cancer diagnosis and positive result for the BRCA1 gene mutation (“I’m going to have cute boobs till I’m 90,” Applegate told ABC News), and before Gossip Girl writer Jessica Queller published Pretty Is What Changes: Impossible Choices, the Breast Cancer Gene, and How I Defied My Destiny, a memoir she wrote after her mother’s death from hereditary ovarian cancer. Two years ago, PBS had not yet aired Joanna Rudnick’s documentary, In the Family, about families living with the burden of the BRCA genetic mutations.

In other words, besides the online community FORCE (Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered), founded by Sue Friedman, there weren’t many resources for someone like me.

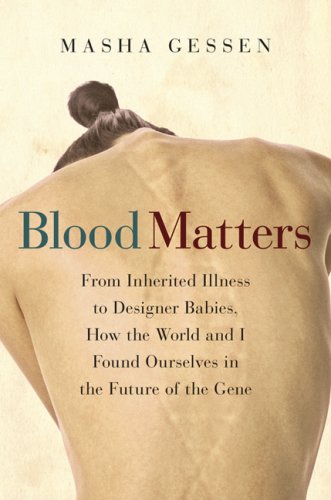

In Blood Matters: From Inherited Illness to Designer Babies, How the World and I Found Ourselves in the Future of the Gene, the book developed from the Slate articles, Gessen repeats a sentiment I appreciated when I first read it two years ago: “I politely suggested I could just shoot myself tomorrow: That would prevent my death from cancer with a 100 percent probability.”

When I mentioned the possibility of preventive surgery to some friends, they suggested I was overreacting. But when I referenced Gessen’s investigations, I didn’t feel so crazy.

When I mentioned the possibility of preventive surgery to some friends, they suggested I was overreacting. But when I referenced Gessen’s investigations, I didn’t feel so crazy.

With access to the world’s best experts, including a 2002 Nobel laureate in economics who quantifies the value of life with the preventive surgeries versus life with cancer, and a psychologist who researches the relationship of beauty to happiness, Gessen details the absurdity of making health decisions as a “genetic mutant.” She interviews a dazzling array of sources and weaves a stunning amount of information into an engaging narrative.

After learning the results of her genetic test, Gessen recounts a tense conversation with genetic counselors, whose nondirective approach only thinly veiled their belief about how best to prevent cancer. Gessen punctures this ostensible neutrality, finding it “as elusive and misguided as the ideal of objectivity in journalism.”

Gessen articulates the lonely and troubling circumstance of knowing one’s genetic destiny. Skeptical of surgery as the only solution, she consults with expert after expert and reviews all the latest medical literature. But eventually she circles back to surgery.

“It came to make sense to me that the frontier of genetic medicine was, in fact, surgical. The simple and decisive nature of surgery is seductive. It is a one-shot deal. Being able to mentally reduce one’s own body to a collection of parts creates a powerful sense of control. Cancer, particularly hereditary cancer, makes this feeling of control especially desirable. Cancer is one’s own cells gone awry. Cutting out the potentially offending organ before it has a chance to betray you shows the body who is boss.”

Blood Matters includes an astounding amount of material about hereditary diseases, behavioral genetics, pre-implantation genetic diagnosis, personalized medicine, and more. Gessen explains medical studies and complex processes with the authority of a scientist, and delivers her stories in lucide, riveting prose. She makes forays into controversial topics such as attempts to link intelligence traits and Ashkenazi Jews, and the search for genetic markers prevalent among particular ethnic groups. Discussing the African American Heart Failure Trial, Gessen addresses the biological imprecision of racial categories: “The only terms less specific [than ‘African American’] might be ‘human.’” She also details the Dor Yeshorim program, a service for young people in Orthodox and Hasidic Jewish communities which aims to prevent severely debilitating genetic diseases such as Tay-Sachs and cystic fibrosis by screening potential mates discretely.

I read Blood Matters on the one year anniversary of my preventive mastectomy. It was difficult to read it without thinking, “This time last year, I couldn’t get out of bed without assistance. This time last year, I was milking drains; I was held together with glue and tape; I was miserable…”

A year later, I’m used to my new body. Even better, I’m not preoccupied with worry. And reading about people in Blood Matters who were faced with Huntington’s disease, a devastating degenerative disease, or people who have had their stomachs removed to prevent stomach cancer, I almost feel fortunate to have only removed my breasts, which after all could be approximated through reconstruction.

Gessen exemplifies the best of what narrative nonfiction can encompass: candid and compassionate stories about her mother, partner, and son; profiles of researchers and their research; and interviews with families affected by genetic disorders. She tours a silver-fox farm where Siberian researchers breed generations of friendly and mean rats and describes the complex terrain of behavioral genetics. I was so excited about what I was learning in the book that I’d find a way to steer everyday conversations to maple syrup disease in Old Order Mennonite children and the four mothers of the Ashkenazim.

At times, reading Blood Matters can feel a bit too much like reading a book of essays on genetics, albeit fascinating, incredibly well-researched ones. The book’s structure, in three parts – “The Past,” “The Present,” and “The Future” – offers only a loose organization; on subsequent readings, I read the chapters out of order, as if I were skipping to favorite songs on an album. But throughout, Gessen makes the material come alive in the way only a great storyteller and journalist of the highest caliber can. Anyone taking a genetics class or interested at all in heredity or the future of personalized medicine should read this book. Genetic medicine is not the future, it’s now, and Gessen’s Blood Matters is an illuminating primer.

One response

Terrific review, Grace. Looking forward to checking out the book.

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment.