In this Rumpus original, Steven Soderbergh talks to Stephen Elliott and Scott Hutchins about his shaken faith in the power of film, what he has in common with Fidel Castro, and how nothing will ever be solved in the Middle East as long as monotheists are involved.

Steven Soderbergh is in San Francisco, promoting the general release of his new four-hour epic, “Che,” starring Benicio Del Toro. When asked how the promotional tour was going, Soderbergh complained that he’d already done about 150 interviews, but he’s glad he’s getting to talk about Che Guevara.

Steven Soderbergh is in San Francisco, promoting the general release of his new four-hour epic, “Che,” starring Benicio Del Toro. When asked how the promotional tour was going, Soderbergh complained that he’d already done about 150 interviews, but he’s glad he’s getting to talk about Che Guevara.

“It helps anytime you can get into politics,” he says. “Anytime you’ve got something that can take you into the political realm then you’ve opened up the conversation a lot. You don’t get as many of the, you know, ‘What’s Brad like?’”

There are two of us interviewing Soderbergh, but we have condensed ourselves into a single non-fiction character, The Rumpus. In this interview Stephen Elliott and Scott Hutchins become one person, the collective “I”.

The Rumpus: I love so many of your movies, but they seem very different. I can’t connect “Sex, Lies, and Videotape” to “Out of Sight” to “Traffic.” And I can’t connect “Traffic” to “Che” at all. Am I missing something there?

Soderbergh: The good news is that I don’t have to know if there’s a link. Wells had a great quote once where some critic asked him a similar question. He said, “I’m the bird, and you’re the ornithologist.” I don’t really sit down and think on a macro level how or if these things are connected. They obviously are in the sense that I wanted to make them. And so there must be something in them that I’m drawn to.

There’s probably a commonality in protagonists who feel through sheer will they can make things turn out the way they want them to turn out, and Che’s the most extreme example of that. But in that regard he’s not that much different than Jack Foley in “Out of Sight.” Or Graham Dalton in “Sex, Lies.”

Rumpus: When people talk about your movies they often talk about the two different Soderberghs. There’s the Soderbergh who does the big projects, and there’s the Soderbergh who does the smaller movies. Do you see your films in that way?

Soderbergh: That’s a delineation that only somebody who doesn’t make movies would make. They’re all for me. I’m not going to spend two years of my life on something that I’m not excited about. And they both have their pleasures. But the process is remarkably similar when it comes down to it. When you’re trying to shoot a scene, the problems are almost identical. It’s just you have more people standing around.

Some filmmakers, you know, have their style and then they kind of go looking for the movie. I’m not like that. I don’t have one style that I want to take from movie to movie. I think that may be a result of an eclectic upbringing. My father, who was the one who really got me hooked on movies, liked all kinds of films, and I saw all kinds of films at a very young age. So especially when you’re starting to make films, and you’re  seeing everything from studio movies to “Last Year at Marienbad,” at a time when things really imprint in a way that’s unique – I’m talking about from around 13 to 17 – [it has an effect]. I was lucky that I was getting exposed to a lot of different kinds of films during that period, and I was liking them all. So it seemed logical to me that you could – as in the style of the studio directors of the 30s and 40s – jump from one genre to the next, with the same satisfaction.

seeing everything from studio movies to “Last Year at Marienbad,” at a time when things really imprint in a way that’s unique – I’m talking about from around 13 to 17 – [it has an effect]. I was lucky that I was getting exposed to a lot of different kinds of films during that period, and I was liking them all. So it seemed logical to me that you could – as in the style of the studio directors of the 30s and 40s – jump from one genre to the next, with the same satisfaction.

Rumpus: Though I do see a common thread in your projects, which is a real interest in story. Even your smaller projects have a strong story to them.

Soderbergh: I’m probably more character-driven than plot-driven. It’s rare for me to attach myself to an idea for a story. “A meteor hits planet Earth” – that’s a story idea but that doesn’t give me any indication of what the character is. Whereas “Out of Sight,” is about a guy who puts himself at risk because he becomes obsessed with the woman who’s trying to put him in jail. That’s an idea that’s about his character, as opposed to the larger issue of how bank robbers operate.

Soderbergh: I’m probably more character-driven than plot-driven. It’s rare for me to attach myself to an idea for a story. “A meteor hits planet Earth” – that’s a story idea but that doesn’t give me any indication of what the character is. Whereas “Out of Sight,” is about a guy who puts himself at risk because he becomes obsessed with the woman who’s trying to put him in jail. That’s an idea that’s about his character, as opposed to the larger issue of how bank robbers operate.

I tend to be drawn more to people than pure story ideas. So you find the character and then you have to deal with another issue, which are the forms you have available. Everything had been done long before I started making movies. I mean, there’s nothing that Godard hasn’t already done. You can’t do a single thing that Godard hasn’t already thought of. And so you struggle to do something that is not predictable.

Rumpus: What were your thoughts on the character of Che?

Soderbergh: I was interested in his will, just the strength that he displayed. It’s kind of unusual. Here’s someone who’s been exposed to things that really outraged him. His ability to turn that outrage into action and never waver is really unusual. I mean, we all get outraged by things and there are things that make us angry and maybe for a while we get angry enough to actually go do something about it. But we’re talking about a guy who for ten years, every day, got up and did something really difficult. And chose the hard way to do it. That’s not normal, especially in someone who’s an atheist. You see this kind of fervor all the time in people who pay tribute to a higher power, who say, “I’m inspired by a higher power,” “I’ve been called by a higher power,” and that’s where they draw their sustenance. He’s the opposite. He believed that everything that’s going on is happening here. And what fascinated me was that he kept his dedication without ever calling on something bigger than him for strength. The reason I was drawn to the jungle part of his life is because it’s the purest expression of that strength.

Soderbergh: I was interested in his will, just the strength that he displayed. It’s kind of unusual. Here’s someone who’s been exposed to things that really outraged him. His ability to turn that outrage into action and never waver is really unusual. I mean, we all get outraged by things and there are things that make us angry and maybe for a while we get angry enough to actually go do something about it. But we’re talking about a guy who for ten years, every day, got up and did something really difficult. And chose the hard way to do it. That’s not normal, especially in someone who’s an atheist. You see this kind of fervor all the time in people who pay tribute to a higher power, who say, “I’m inspired by a higher power,” “I’ve been called by a higher power,” and that’s where they draw their sustenance. He’s the opposite. He believed that everything that’s going on is happening here. And what fascinated me was that he kept his dedication without ever calling on something bigger than him for strength. The reason I was drawn to the jungle part of his life is because it’s the purest expression of that strength.

Rumpus: The Bolivian part.

Soderbergh: Cuba and Bolivia. Just being out there in the middle of nowhere with the gun. In looking at his lifeline, I couldn’t help but notice that he kept going back to the jungle. I thought, then obviously there’s something there that compels him. When we got out to shoot the thing, I got a better sense of what it was. There’s a real simplicity and a purity to being out there doing one thing, where you have one goal. I can see why he felt he was the best version of himself in the wild.

Rumpus: What was the original thing that brought you to Che? Of course, you’d heard of him, but was there a moment when you thought, “I’ve got to do a movie about this guy?”

Soderbergh: No. Laura and Benicio [Laura Bickford and Benicio Del Toro, the film’s producers] brought the project to me.

Rumpus: So you never owned a Che shirt?

Soderbergh: (laughs) No. I couldn’t have been less knowledgeable when they brought this up.

Rumpus: But he’s such a political symbol. What were your motivations? What were you thinking about when you decided to make this movie?

Soderbergh: I was just thinking about what I always think about: what do I want to see? What would  I want to see if I went to see a movie called “Che”? In this case, a lot of people have a very personal idea towards him, and the film isn’t very concerned with that. (laughs) It’s not a movie about feelings. And a lot of people go to the movies wanting the movie to be about feelings, and it’s really not about that. Or rather it’s about feelings in the abstract. It’s about his feelings regarding building a better society. And it’s about his feelings regarding the removal of exploitation as a profit-making method. But on a one-on-one level, he’s not a very emotive person. That’s what I got from all the research we did. And my refusal to sort of manufacture an emotion or a sense of drama that wasn’t there is annoying to some people.

I want to see if I went to see a movie called “Che”? In this case, a lot of people have a very personal idea towards him, and the film isn’t very concerned with that. (laughs) It’s not a movie about feelings. And a lot of people go to the movies wanting the movie to be about feelings, and it’s really not about that. Or rather it’s about feelings in the abstract. It’s about his feelings regarding building a better society. And it’s about his feelings regarding the removal of exploitation as a profit-making method. But on a one-on-one level, he’s not a very emotive person. That’s what I got from all the research we did. And my refusal to sort of manufacture an emotion or a sense of drama that wasn’t there is annoying to some people.

Rumpus: Is there political pushback? Are you getting grief?

Soderbergh: Oh, sure, sure. The Q&A in New York when the movie opened was pretty interesting. A lot of people screaming and yelling.

Rumpus: What are they screaming?

Soderbergh: They screamed what they scream in the movie. “Murderer.” “Assassin.”

Rumpus: They were anti-Che?

Soderbergh: Oh yeah. The people that like Che tend to come away saying, “Oh, I didn’t know that.” The people that are anti-Che just see it as a commercial for him. Some of them can’t really get beyond the idea of a Che movie. For them, by definition if you make a movie of him you’re supporting him. It’s impossible for them to understand that’s not how art works. That that’s not how an artist works. I can make a movie about Lee Harvey Oswald and make you feel what he feels and make you understand why he believes what he believes. That doesn’t mean I think you should go out and shoot JFK. They [the anti-Che critics] see the movie, and there’s no amount of accumulated barbarity that will satisfy them. For them, he is defined by the events at La Cabaña right after the revolution. That is him, for them. My whole thing is, yeah, that’s part of him. But I don’t define him by that. That seems to me to be consistent, actually, with the rest of him. If you saw the film and then you went and, say, researched him on the Internet, would you be shocked by La Cabaña? Would you say, “Wow, that doesn’t seem like the same guy?” I don’t think so. This is a guy that felt, “Yeah, you gotta kill people. This is a revolution. That’s what happens. I could get killed.”

Rumpus: And he does, at the end of the second movie.

Soderbergh: That’s my other response when they get really upset. I say, “Well, didn’t you like the last thirty minutes of Part Two? That should be like snuff porn to you.” At least this is a guy who really walked the walk. He didn’t have to go to Bolivia.

Rumpus: It didn’t seem he was even wanted there.

Soderbergh: No, he wasn’t. And the story of the Congo, which we couldn’t get into, was similar. Kind of a dry run for Bolivia. But, again, people didn’t want him there. He didn’t get on with the local revolutionaries. The indigenous African rebels didn’t get on with the Cubans. It’s a fascinating story and I would have liked to do it, but we just didn’t have time.

Soderbergh: No, he wasn’t. And the story of the Congo, which we couldn’t get into, was similar. Kind of a dry run for Bolivia. But, again, people didn’t want him there. He didn’t get on with the local revolutionaries. The indigenous African rebels didn’t get on with the Cubans. It’s a fascinating story and I would have liked to do it, but we just didn’t have time.

Rumpus: Getting off topic a bit…you talked about your teenage years, and about being imprinted by them. You spent your teenage years in Baton Rouge, where your dad worked at LSU. I was wondering if you saw yourself in any way as a Southerner?

Soderbergh: Well, I grew up mostly in the South, and there’s definitely something about the South that’s different from the North. When people ask me where I’m from, I say Louisiana. I spent more years there than anywhere else. I have a friend whose theory is that you’re from wherever you went to high school. I think that’s mostly true. There’s definitely a way of thinking and a way of being in the South that has its advantages and disadvantages.

Rumpus: I was definitely struck in “Schizopolis” with the Southerness of the main character’s romantic interests. [In “Schizopolis,” Soderbergh plays both the main character and his doppelganger.] There’s a kind of free-floating Southerness in the accents.

Rumpus: I was definitely struck in “Schizopolis” with the Southerness of the main character’s romantic interests. [In “Schizopolis,” Soderbergh plays both the main character and his doppelganger.] There’s a kind of free-floating Southerness in the accents.

Soderbergh: Absolutely. My first wife was from the South. She talks that way. If you get a couple of drinks in me, you can hear that I spent a lot of time in the South. And there’s a great story telling tradition in the South. A great oral story-telling tradition that I think is interesting.

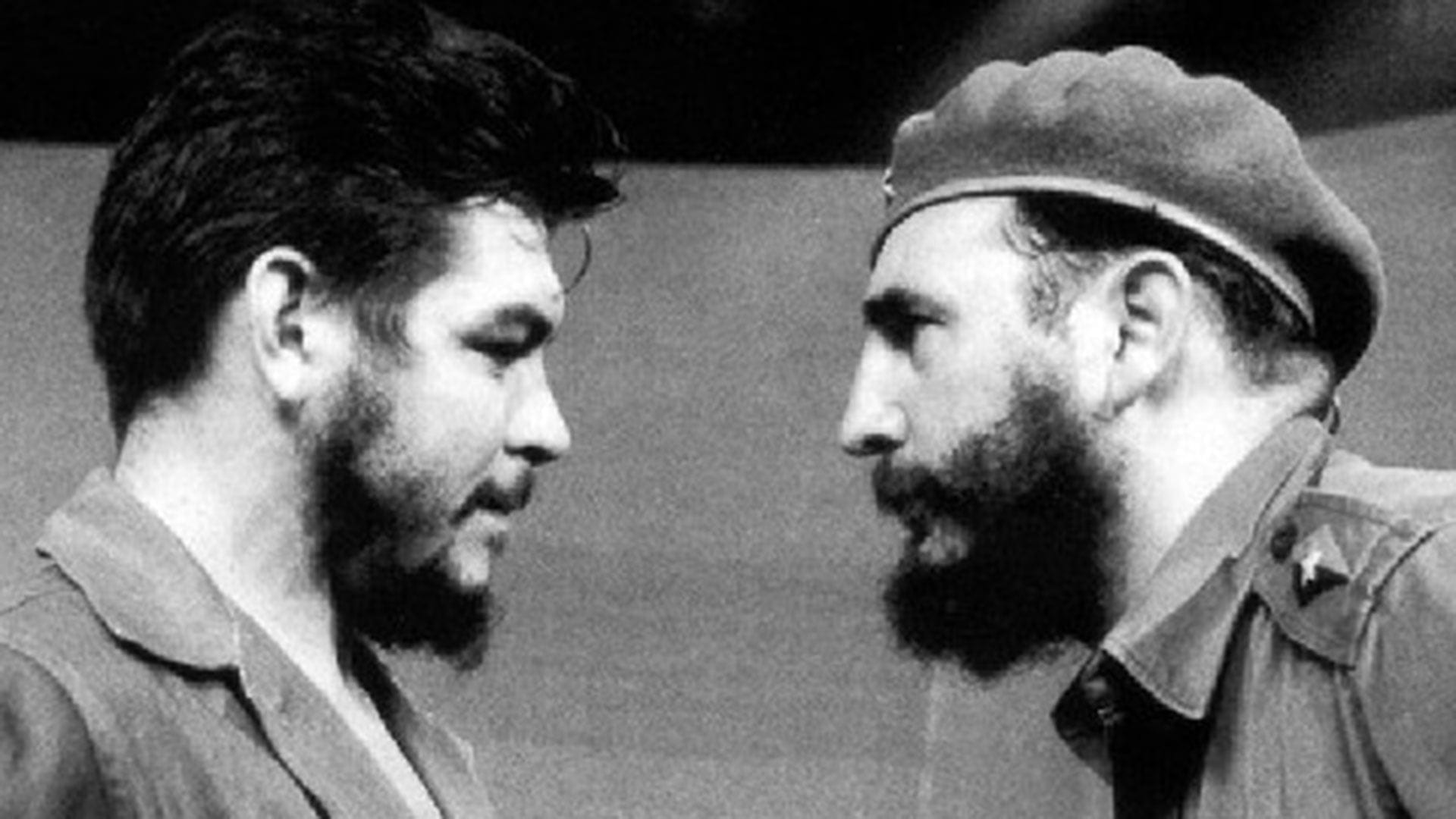

Rumpus: Back to “Che.” One of the things I wondered about was how charismatic Castro is in the movie. And I wondered, is Che really just a good second in command? Is he just Trotsky to Castro’s Lenin?

Soderbergh: Oh, absolutely. I mean, that’s what Bolivia [Part Two of the movie] is about. I mean, we don’t know what Che believed, but there are two possibilities. Either Che didn’t understand that [dynamic], or he thought that he was that.

Rumpus: The Castro figure.

Soderbergh: Yes. And neither necessarily paints him in a positive light. If you’re not smart enough to know what Fidel meant during the Cuban revolution, that – when they were on the Granma [the leaky boat they took to Cuba, a famous moment of the Cuban Revolution and a key scene in the movie] – Fidel was already a rock star in Cuba, and how important that was to the indigenous population, then you’re not paying attention. And if you think that because you’re Che, when you go into Bolivia, when people find out it’s you, that they’re going to have the same kind of reaction that the Cubans had to Castro, then you’re high.

It really is an aspect of his belief system that you have to wonder about. How could you not understand that without a Fidel you’re going to have a problem here?

Rumpus: Castro, for me, more than any other character in the movie, was really bright and shiny and alive.

Soderbergh: Castro, without question, is one of the smartest politicians that’s ever walked. This guy is really, really, really smart. It has nothing to do with whether you agree with him. I’m just saying that this guy is really smart.

Soderbergh: Castro, without question, is one of the smartest politicians that’s ever walked. This guy is really, really, really smart. It has nothing to do with whether you agree with him. I’m just saying that this guy is really smart.

You can see all the seeds of it in Part One. Like how he sees the macro of all of it. And how everyone he encounters is kind of being weighed by him. That just how he thinks. He’s the best at sort of pinpointing who will be a great resource.

I mean that’s what you do as a director.

Rumpus: Wait – are you saying you see yourself in Castro? Is Castro the Soderbergh in the film?

Soderbergh: I’m just saying I didn’t judge that way of thinking, because I felt like that’s exactly what I do. I meet someone and I think, “Now, how can I use this person?” Then I suck them dry and throw them away.

Rumpus: You also bring out the best in them…

Soderbergh: Fidel would say the same.

Rumpus: … I think of Jennifer Lopez and Julia Roberts as two examples. My favorite performances by those two actors come in your films. And George Clooney is a different actor before he meets you and after, I think.

Soderbergh: Your job is to create a situation in which the best that they have is allowed to come out. I’m not getting anything out of them that isn’t there. I’m not one of these I’m going to reach down their throats and pull the performance out. I hate that shit.

Rumpus: When you cast a star do you think that’s the best person for the role, or is it because you want to have a star in your movie?

Soderbergh: I’m not a snob. If I feel like there’s a star that’s the best person for that role, then that’s who I get. And sometimes I might feel like [a movie] is kind of a weird idea and if I’m going to get enough money to execute it properly I’ve got to get somebody in it that is going to justify the expense. But I think there are only two times that I’ve ever ended up paying somebody their quote. Like what they actually were worth in the marketplace. In all the other movies I’ve made – including all the Ocean’s films – everybody worked for way under what they normally get, in order to make the film. If they all got paid normally, you couldn’t make the movie.

Rumpus: It’d cost a billion dollars.

Soderbergh: Yeah. And I’m a big believer that if there’s something you really want to do, don’t walk away because of the deal. I see it happen a lot. I see people walk away from things because they didn’t get the deal they wanted.

Rumpus: What does that mean exactly?

Soderbergh: If I’m a director and I read a script and I say yeah I really want to do this, I would never walk away because the deal wasn’t very good – that I wasn’t getting paid very much or that the chances that I would see anything on the back end were remote because of the financial waterfall and the way it’s structured. I would never use that as a reason not to do something. A lot of people do. I think that’s always a mistake.

I mean, the Che deal is the worst deal a director had ever made in the history of motion pictures. I guarantee it. It’s awful. I mean, I’ve got so much of my own money in the project, and the way I’m being paid…it’s hard to explain how far I am from any money that’s coming in. But what, am I not going to make the movie? Who cares? And, you know, if I direct a movie for scale, like on “The Girlfriend Experience” – the movie I just finished shooting – that’s more than my dad ever made in a year. Ever.

Rumpus: Can you tell Sasha Grey (the star of The Girlfriend Experience) to do an interview with us? Because we’ve really been trying to get her to do an interview.

Rumpus: Can you tell Sasha Grey (the star of The Girlfriend Experience) to do an interview with us? Because we’ve really been trying to get her to do an interview.

Soderbergh: Don’t worry. When the movie comes out you have an interview. [The Rumpus says: You heard it here, Sasha.] She’ll be talking to you. She’s great in the movie. She’s going to surprise people. We just screened a version of it for some friends. I had like 30 people come, and they were really surprised by her.

Rumpus: To wrap up…when you won the Oscar you dedicated your speech to artists, to all the people who create, which I found really inspiring at the time. But I read in a recent interview where you said that if a movie can’t stop the stoning of that thirteen-year-old rape victim in Somalia, what good is it? Are you not feeling positive about the power of movies?

Soderbergh: No.

Rumpus: Has your faith in art been shaken? What about your movies, your life as a filmmaker?

Soderbergh: Well, I feel I’m closer to the end of it than I am to the beginning of it, in terms of my career. But yeah I still have that question. Or rather I feel I need to really think about whether there’s a way to use what skill I have to address things that outrage me, like the 13 year old girl getting stoned to death. Because I don’t think making a movie is going to help that, or change that.

Rumpus: We just saw “Waltz with Bashir” last week, which is a movie that I think – it’s not necessarily going to change the world – but a lot of people are learning a lot of new stuff because he found a new way to get them the information. I mean, don’t you feel that way?

Soderbergh: No. Because it doesn’t go deep enough.

Rumpus: That particular movie, or movies in general?

Soderbergh: Any discussion about the Middle East that doesn’t start with whether monotheism is a good thing or a bad thing is an irrelevant discussion. This is all based on the fact that some people think that a certain piece of land that was host to some events two thousand years ago has magic meaning. I don’t believe that. I think dirt is dirt. Why people are still fixated on this idea of having this particular piece of dirt – I don’t understand it. That dirt isn’t worth one life to me. So you can sit and talk about who had what when and that, but it goes back to a deeper question of our need to create a narrative with this force that is acting upon us. Until we address whether that’s smart or dumb nothing’s going to get solved.

Rumpus: You’re talking about both sides of the conflict.

Soderbergh: Yeah.

Rumpus: But you don’t feel you can do that with your films? You don’t feel you can address those feelings?

Soderbergh: I think we’re hardwired, unfortunately, to keep making the same mistakes over and over. More and more elaborate versions of the same mistakes.

Rumpus: But does that make your films irrelevant?

Soderbergh: Yeah.

Rumpus: You don’t think you could make a relevant film within that context?

Soderbergh: I don’t think so. (Thinks.) It would be a miracle.

**

See Also: The Rumpus Long Interview with Tamim Ansary

See Also: Fade To Orange, Michelle Orange’s Film Link Happening

See Also: Ryan Boudinot’s The Eyeball

One response

Sir:

Would you please e mail me Steven Soderbergh’s e mail address. I would like to submit my murder mystery book to him for consideration. I have been unsuccessful in finding his address on my own.

Thank you for your time,

Bev Garant

1267 Tilston Drive

Windsor, Ontario

N9B 3C6

519-252-1691

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment.