Abject admiration is the worst way to start a review. Isn’t it the blurbist’s job to kiss a writer’s behind, the critic’s to skewer it on the formidable barb of his or her literary intellect?

Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum has proven herself inimitable, capable of scavenging a universe of love and disappointment from the smallest crumbs of human experience. In Ms. Hempel Chronicles, a card trick, the slamming of a car door, can redeem twenty-odd years of unexamined existence. A kiss bears within it a quiet lesson, apprehended only by a shifting of muscle and skin, a change in physical and atmospheric pressure: “So that was what it felt like, someone making a decision.”

This is modest, patient, unrivaled work, which is terrific for Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum and terrible for book reviewers. Abject admiration is the worst way to start a review—surely one must have cavils, objections, clever observations. Isn’t it the blurbist’s job to kiss a writer’s behind, the critic’s to skewer it on the formidable barb of his or her literary intellect?

But what if the book is just that good? What if it doesn’t allow for complaints or cleverness? What if it leaves one with a sense of wonder, of loneliness, of renewed faith in contemporary fiction?

Ms. Beatrice Hempel teaches seventh grade. A late-twenty-something, she finds herself struggling with a career that had once “seemed to offer both tremendous opportunities for leisure and the satisfaction of doing something both generous and worthwhile.” While she’s been spending her evenings in front of the television grading papers, her friends, lovers, students, family members, even other teachers have begun to pass her by—they’re on their way to their own lives, of course. Bynum explores Ms. Hempel’s relationships with these other characters as they disappear into the distance, her sense of diminishment and loss, her fierce jealousy and even fiercer empathy.

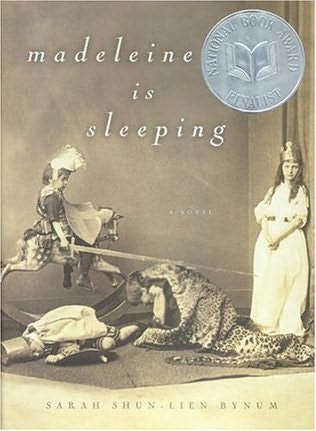

Admittedly, this doesn’t seem like the sort of book that will revolutionize contemporary American literature. A book about a nice teacher—well, that sounds nice. And it’s true that Bynum’s material here is not as imaginative or experimental as it was in her first book, the National Book Award finalist Madeleine Is Sleeping, a sinuous traumwerk narrative that followed the erotic fantasies of a sleeping young girl into and out of what you or I might think of as reality.

The truth is that most of the things that happen to Ms. Beatrice Hempel don’t happen to her. Her engagement to a long lost high-school friend brings a sharp new joy to what she perceives to be a faded life—but that promise is mysteriously erased by the last third of the book. Whatever happened to handsome Amit, who sang and danced and ran miles every day in a pair of spectularly thigh-baring shorts? Readers are given only a series of half-uttered regrets, conversational slips, another woman’s name spoken only once. This curious plot structure, threaded through eight episodic chapters, prevents the kind of angry emotional confrontation common to little books by young authors.

The truth is that most of the things that happen to Ms. Beatrice Hempel don’t happen to her. Her engagement to a long lost high-school friend brings a sharp new joy to what she perceives to be a faded life—but that promise is mysteriously erased by the last third of the book. Whatever happened to handsome Amit, who sang and danced and ran miles every day in a pair of spectularly thigh-baring shorts? Readers are given only a series of half-uttered regrets, conversational slips, another woman’s name spoken only once. This curious plot structure, threaded through eight episodic chapters, prevents the kind of angry emotional confrontation common to little books by young authors.

Ms. Hempel Chronicles doesn’t sacrifice accessibility or sense of humor for affect or style—it entertains. It is a friendly book, possessed, like its protagonist, of only the quietest rebellion. Ms. Hempel’s mother is Chinese; when another teacher suggests she call herself Ms. Ho-Hempel to emphasize her ethnicity she replies, “Won’t there be a lot of jokes?… You know, ho? As in ‘pimps and.’ As in, ‘you blankety-blank—’” She trails off. She is, as always, flustered and innocent and possessed of a forthrightness that is its own grace. This baffled candor—which is not simplicity, nor childishness—isn’t something one is used to reading these days. It isn’t exactly fiction: It is embarrassingly true.

Bynum’s descriptions of the young folk who make up Ms. Hempel’s universe are enough to make the book worth reading (twice). There’s Jonathan Hamish, a difficult student who murmurs, “Mercutio’s the man,” during a lesson on Romeo and Juliet; and “Harriet Reznik, precious artifact of another age! Her thick swingy helmet of hair, the bangs that looked as if they had been cut with the help of a ruler.” Anyone who has been a student, and loved a teacher or a mentor—and suspected they were loved in return—will recognize these portraits and delight in Bynum’s apt handling of the delicate relationships between such dynamic characters.

The young Beatrice has her own memories of teachers, such as the history teacher who “looked to her hopefully during a discussion of immigration. She scowled. Typical, she thought. She wrote a poem about it.”

Typical, she thought. She wrote a poem about it. Understanding why this is so funny, goes a long way toward explaining why Ms. Hempel Chronicles is such a wonderful book. Here we have an adolescent person doing something absolutely typical—feeling misunderstood or exploited, then writing a poem about it—because a grown-up person has done something absolutely typical—cast about him for the nearest human mooring in a discomfiting situation. That Beatrice Hempel, age fourteen or so, uses the word “typical” is, in itself, typical. Could one more adroitly depict the idiocy of the situation, while simultaneously—mercifully—humanizing both the insensitive adolescent and the insensitive adult?

Ms. Hempel teaches English, one should specify. Or, she teaches “reading and writing and critical thinking.” She assigns her students Tobias Wolff’s memoir This Boy’s Life, and asks them to discuss what it means to write from life. Later, she has to defend her choice at a parents’ meeting, since the book contains, among many thousands of others, the words “shit” and “fuck.”

Now, a book about books runs the risk of being obnoxious, and it’s easy to say, as Ms. Hempel does to the parents, that there’s something wonderful about Tobias Wolff—the “authenticity of the voice,” for example, or a certain omnipresent “shock of recognition.” But Bynum goes farther, demonstrating that a book isn’t good just because it contains a story: It must induce other people to tell their own. Ms. Hempel’s class insists that she tell them about her childhood, and what emerges is a half-told tale of lost promise, the book’s very heart.

Equally characteristic to her writing is a vividness of description and detail, a self-effacing verve to match Ms. Hempel’s lucid, if baffled, self-perception. One of her students is a “sad sack, hanger-on, misplacer of entire backpacks.” Her younger brother has “the personality of a dandelion or a patch of crabgrass.” And Bynum makes perhaps the best use of an exclamation point in the last several years of contemporary fiction; you’ll know it when you see it and it will move you more than you thought punctuation ever could.

Ms. Hempel has a style, too. She is called an “affable” teacher by one girl, but knows, unfortunately, that this is “not synonymous with good.” In Ms. Hempel Chronicles, learning to describe the world—and one’s place in it—furnishes a series of bittersweet revelations. During her childhood, Beatrice’s father often leaves the family for mysterious weekend camping trips. This enrages his wife and confuses his children, though they try to go about their routines—chopping vegetables, working on their science homework. But “Beatrice, confronted with the mystery of her father, the mystery of her mother, could only write repeatedly, in ever tinier cursive, Canoeing is a perilous outdoor sport.”

The perils of canoeing here are literal, and also figurative. The more Beatrice carves that tiny phrase into her notebook the more its obscurity becomes a sanctuary from her family, the screaming fights, the Saturday-Sunday silences. But her writing, to put it frumpily, also indicates a nascent understanding of the redemptive power of language. Beatrice intuits the power of that sentence, centered on the many—mostly grim—senses of the word perilous, and tinged with melancholy humor by the phrase outdoor sport. She writes in “ever tinier cursive,” delicately, self-effacingly, but with genuine, irrepressible anger and fear.

Which makes it seem, strikingly enough, that Beatrice would have made a good writer. She might have turned out something like Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum—one of the very best. For it is Bynum who shows us that there’s nothing better than a writer who teaches and a teacher who writes.