“…The day that you don’t have any Republican friends, or you don’t have any Christian friends, or you don’t have any Muslim friends, that you only have, like, artists-from-New-York-City friends, then I think you have a problem.”

“…The day that you don’t have any Republican friends, or you don’t have any Christian friends, or you don’t have any Muslim friends, that you only have, like, artists-from-New-York-City friends, then I think you have a problem.”

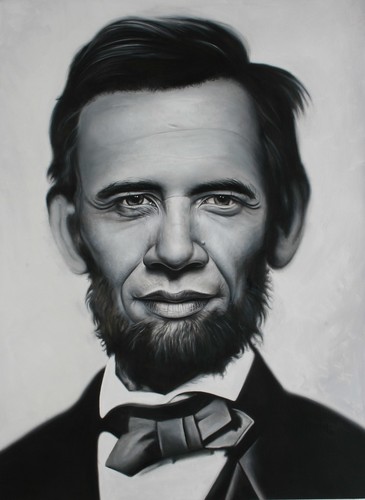

Ron English is the New Jersey artist who merged the mugs of Abraham Lincoln and Barack Obama into one of the most iconic images of the 2008 presidential campaign. He’s also known for “liberating” corporate billboards with his own provocative anti-smoking, corporate-bunking, and progressive political messages. Born in Texas in 1966, English is a radical supporter of free speech and social equality. As a world-renown artist, a musician, political activist and father of two, he’s both a controversial character and model citizen.

The Rumpus: How would you describe the difference between street art and vandalism?

The Rumpus: How would you describe the difference between street art and vandalism?

Ron English: Well, it’s illegal when it’s vandalism, right? Street art isn’t malicious. Vandalism would apply to some malicious intent, and I think that street art has quite the opposite intent.

The Rumpus: How about your point of view on the boundaries between privacy and piracy, and ownership?

Ron English: I’m not somebody who believes that a very few people can own everything. I know that’s a radical belief. I always thought, like, what if we all lived on a little island together and there were only twenty of us. But you owned the island and there was only one source of drinking water, and you owned the drinking water, you owned that pool that had the drinking water. And then you decided, “You know what? I’m gonna start urinating into my drinking water.” You see what I mean? It starts a lot of problems when very few people own everything.

The Rumpus: I think of your work as an act of civil disobedience. Would you agree with that?

Ron English: Oh, absolutely. But also I don’t really damage the billboards. They’re posters and I put up posters, so I’m cycling in a message that they don’t want on their billboards. At the same time it’s not damaging their billboard. They continue the same process they’ve already started. They go out and put up the next ad.

Ron English: Oh, absolutely. But also I don’t really damage the billboards. They’re posters and I put up posters, so I’m cycling in a message that they don’t want on their billboards. At the same time it’s not damaging their billboard. They continue the same process they’ve already started. They go out and put up the next ad.

The Rumpus: Has your art always been an act of civil disobedience? When did you first realize that your art could be a form of rebellion?

Ron English: When I moved into a house populated with members of Earth First in Austin, Texas. They were an environmentalist group in the 80s who later were accused of terrorism. They [the accusers] actually kind of slaughtered their group. I think the opposition had some really good tactics to use against them. They weren’t terrorists. They were just more radical than the Sierra Club.

The Rumpus: How did that motivate your work?

Ron English: I think they pointed out the possibility that art could do something besides being a diversion.

The Rumpus: You’ve gone to prison many times and you’ve been sued like crazy. But your art really reflects a strong sense of social responsibility.

Ron English: Right, but I’ve never lost a lawsuit. They do harassment lawsuits. The way they look at the landscape is you’re doing something they don’t like but it’s not illegal.

The Rumpus: Do they sue for damages?

Ron English: Oh, no, I haven’t been sued by the billboard companies. I’ve been sued by King Features for making parodies of Charlie Brown, or Disney for making parodies of Mickey Mouse. But it’s completely legal. The law is completely on my side. The way they’ve looked at it in the past is, if they sue me it will cost me two hundred thousand dollars to lawyer-up and fight them. No artist has two hundred thousand dollars. They would cripple me to the point that I wouldn’t ever do it again. I wouldn’t follow suit with a lawsuit because I couldn’t afford it. But the thing is when you live in New York you can use the Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts. So, once they look across the table and see you have the top lawyers in New York, they realize you’re not having to shell out a single penny, usually they drop the lawsuit. All that has changed since the lawsuit that—god I’m forgetting the guy’s name [Tom Forsythe]. He did “Barbie in a Blender.” His work used Barbie as a cultural icon. And the only people that actually ever bought it were Mattel. And the only reason they bought it was because they wanted to file suit against him. But they lost the suit, and they had to pay a million and a quarter dollars to not the artist but his lawyer because he used Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts. I think that nobody wants that outcome. And I’m probably the worst case to go against because I have such a huge reputation as a being a political activist and my art is obviously parody.

The Rumpus: Do you still think of yourself as an “outlaw” artist?

Ron English: I would like not to think of myself as an outlaw artist, but I still seem to be one. At some point you have to join the establishment, right?

The Rumpus: I suppose. Or work with it. Maybe not join it.

Ron English: I try very, very hard. Like, we did this stuff for Obama. And we went across the country for those Abraham Obamas. I never put one up anywhere except on walls not on billboards, and I got permission for every wall. And it was a lot of extra work that I’m not used to doing. It took two weeks to get somebody to let me put one on a construction wall, and they took it down about twenty minutes later. You know, because somebody else in the organization came out, from meetings after meetings, ‘What are you gonna put up there? Bluh bluh bluh.’ I went through that just not to bring any taint onto his campaign, so the Republicans couldn’t say, ‘Well you know he has this outlaw artist working for him now.’

Ron English: I try very, very hard. Like, we did this stuff for Obama. And we went across the country for those Abraham Obamas. I never put one up anywhere except on walls not on billboards, and I got permission for every wall. And it was a lot of extra work that I’m not used to doing. It took two weeks to get somebody to let me put one on a construction wall, and they took it down about twenty minutes later. You know, because somebody else in the organization came out, from meetings after meetings, ‘What are you gonna put up there? Bluh bluh bluh.’ I went through that just not to bring any taint onto his campaign, so the Republicans couldn’t say, ‘Well you know he has this outlaw artist working for him now.’

The Rumpus: Let’s talk about your childhood and how your childhood influences your work. You grew up in a trailer in Illinois, is that right?

Ron English: I was very young when I was in a trailer. Then we moved to a house.

The Rumpus: And I read that your mother was a reluctant painter. Is there anything about your childhood that influences your art?

Ron English: I think my dad didn’t really want my mom to be an artist or to be doing that sort of stuff. I don’t know if he understood what that was. So I think that she encouraged me to be an artist and she helped me a lot with my art.

The Rumpus: How did she encourage you?

Ron English: When I made 8mm movies she made the costumes for the movies. Some really elaborate costumes. She taught me how to use tools and make puzzles. I think she just really encouraged the art thing. Until I was in high school [laughs] and started getting into a lot of trouble for it. I made an underground comic book that created a lot of controversy.

The Rumpus: What was controversial about it?

Ron English: You know, I never meant in my life to be controversial. I think it’s just this kind of impish nature that I have. My dad had that kind of a weird sense of humor that a lot of people didn’t get.

The Rumpus: Well, I get the controversy, and I get that there’s this outlaw feeling, but I also feel like your work has more integrity and stronger values than a lot of people do. So this whole idea of being an outlaw, it’s sort of a Robin Hood style outlaw. It’s not a negative thing. I think it seems negative because people see the laws as ‘that’s what you should be doing by someone else’s standards.’ But I think you’re subverting that in a positive way, not a negative way.

Ron English: Right, like, when you try to explain it to your kids. I mean, they understand now, but when they were younger they were just like ‘You go to jail a lot. The only people who go to jail are criminals. You’re a criminal.’ And I said, ‘Well who did you learn about in school today?’ And they’re like, ‘Well, we learned about Martin Luther King.’ And I’m like, ‘You know, he went to jail a lot.’ And you know I’m not trying to compare myself to Martin Luther King! He literally put his life on the line and ended up losing it. But, you know, we like to go home and have dinner after the protests. But I’m just saying that a lot of people that make social change meet with resistance, and the resistance is usually in the form of getting tossed in the can. Not everybody in jail is a criminal.

Ron English: Right, like, when you try to explain it to your kids. I mean, they understand now, but when they were younger they were just like ‘You go to jail a lot. The only people who go to jail are criminals. You’re a criminal.’ And I said, ‘Well who did you learn about in school today?’ And they’re like, ‘Well, we learned about Martin Luther King.’ And I’m like, ‘You know, he went to jail a lot.’ And you know I’m not trying to compare myself to Martin Luther King! He literally put his life on the line and ended up losing it. But, you know, we like to go home and have dinner after the protests. But I’m just saying that a lot of people that make social change meet with resistance, and the resistance is usually in the form of getting tossed in the can. Not everybody in jail is a criminal.

The Rumpus: I read a great interview that you did with your kids. One thing that struck me particularly was that Mars told you that he was going to grow up to be a ‘naked dumpster diver.’

Ron English: [Laughs] Yeah.

The Rumpus: Is there any career that you can imagine him choosing that you might not be cool with?

Ron English: I’m ninety percent sure Zephyr is going to be a writer. She’s a really good writer. Mars is really technical. He programs our VCR and our telephones and he’s always done that kind of stuff. I mean, he got us cable and we still to this day can’t figure out how he got us cable. He’s a little six-year-old boy, and he wants Cartoon Network. He hooked it up and we don’t know what he did. [Laughs] So I’m sure he’s not going to be a naked dumpster diver! They were trying to be funny. They actually got mad when the interview came out because they said, ‘We didn’t know you were interviewing us.’ But I said, ‘I told you that.’

The Rumpus: You have a whole separate creative life as a musician. Your band is The Electric Illuminati, but that’s just one of your many projects. Can you tell me a little bit about the musical side of your creativity? What are you accomplishing with music that you aren’t doing with your art?

Ron English: Well art’s ultimately intellectual, it seems like. Art’s only emotional to a degree. I think people get a lot more emotional over music than they do over visual arts. So some things, I think, are better expressed through music. Like when I did the Revelations thing, I did it twice. I did it as an art show. And then we did it as kind of like a musical odyssey. And I think the music worked a lot better because religion’s really an emotional response to the world and not an intellectual response.

The Rumpus: There’s this little logo of yours, the ying and yang character. It seems like this theme of dichotomy—it’s almost even unholy couplings—runs through your work, like Marilyn with Micky Mouse breasts, Mickey and Bart Simpson at the Last Supper, McStarry Night, and even Abraham Obama fused across centuries. What’s intriguing to you about the fusion of things that seem to be opposite?

Ron English: I think I’ve always been able to hold opposite beliefs in my head without having a conflict over it. When there’s a big controversy it always seems like I understand both sides. Obviously, you pick a side. You think one side is more right than the other. I’m not completely dismissive of the other side. Sometimes I think when you’re a political activist or something, it’s hard to fathom that the other side actually does believe what they’re saying.

Ron English: I think I’ve always been able to hold opposite beliefs in my head without having a conflict over it. When there’s a big controversy it always seems like I understand both sides. Obviously, you pick a side. You think one side is more right than the other. I’m not completely dismissive of the other side. Sometimes I think when you’re a political activist or something, it’s hard to fathom that the other side actually does believe what they’re saying.

The Rumpus: And what can come out of that, do you think? What’s the potential?

Ron English: I don’t know. I think when you’re trying to change people’s minds, people listen to their friends. They don’t listen to their enemies. You get more change by the people you’re closer to, because you can be very dismissive of people that you don’t really have anything to do with. And the people you disagree with you can just ignore them or don’t have anything to do with them. You’re not really going to change them, and they’re not going to change you.

The Rumpus: Do you think it’s something you push yourself toward, to really draw more out of these conflicting or apparently conflicting ideas?

Ron English: Well, I live a weird life because I do live in a bubble even though I go all over the world. Everywhere I go, I’m still in a bubble. I think a lot of politicians, that happens to them. That happened to George Bush. Everywhere he went they put him in a stadium full of people cheering him on, when that only constituted a very small percentage of the world’s population in what they thought. But it would be easy for him to think, ‘Everybody agrees with me.’ Years ago I didn’t know anybody that didn’t vote for Ralph Nader. Obviously very few people had voted for Ralph Nader. And I think you want to make a conscious effort to make sure that, you know, the day that you don’t have any Republican friends, or you don’t have any Christian friends, or you don’t have any Muslim friends, that you only have, like, artists-from-New-York-City friends, then I think you have a problem.

The Rumpus: I think that’s true. I’m curious if there’s ever been a project that you wanted to do but thought, no, not that, that one might be too offensive?

Ron English: Well, usually my wife does that for me. But she’s gotten me into a lot of trouble, too. She’s impish too and gets me to do things that I probably wouldn’t do.

The Rumpus: It’s good to have that close at hand.

Ron English: I think it’s really good to have a mate who is probably more conscious than I am. So that if I want to make a decision like, well, Camel cigarettes said, ‘We’ll give you two hundred thousand dollars.’ And we were pretty broke. So to turn them down, you really want to have your wife on your side, and say ‘You know, we’re going to keep suffering for a few more years.’ And this would have alleviated all of our suffering very quickly. When you make those kind of decisions I think it’s really nice to have somebody that agrees, who wants to go the distance.

The Rumpus: Especially if they’re going to be suffering with you.

Ron English: Yeah.

The Rumpus: You used to have a cable access TV show. What was that like?

Ron English: I think a lot of people had them back then. It was kind of an odd thing because if you lived in Manhattan, and it’s still true, you could have a TV show and a lot of people see it. And it doesn’t cost you anything. You just get a time slot and I think every year they renew it you can try for a better time slot. All you have to do is turn in a tape and you can produce whatever you want.

The Rumpus: What did you do on your shows?

Ron English: It wasn’t that serious. We used to throw a party and then interview different people who came to the party. And we had odd things. Like one of the funniest things I did is, I had a producer and an editor that helped me. So I told the editor—they had just opened a porno shop across the street from my loft—I said go to the porno shop and get like thirty porno tapes, and then take them back and edit out every time like a nipple shows or anything. Cut all that out and just leave the dialogue. It was actually one of the funniest pieces we did because the dialogue—I mean people would get a sentence and a half out before it would turn into sex. People were getting frustrated because it keeps leading up to stuff that doesn’t happen. But about halfway through the show people were rolling on the floor.

The Rumpus: That’s hysterical. If you still have that I think we’d like to run it on The Rumpus.

Ron English: We have some of our old shows. I don’t know if we have all of them. They’re pretty degraded because they were on VHS.

The Rumpus: You’ve done projects on the Separation Wall in Gaza and on the Berlin Wall and around the world. Of all your projects, which one has been the most meaningful to you?

Ron English: The Berlin wall was interesting because there was this group of East Germans that were sitting, protesting. The wall is on the side of East Germany—or it was. So they can actually capture you if you’re within like 10 or 15 feet of the wall. They measured it out and they were, you know, camped there. They were there doing an ongoing protest. I painted for about a week on the wall. And they would sit and watch, because the East German authorities were trying to catch me. So I would be so absorbed in my painting. What they would do is come around the wall and quietly tried to walk up and, you know, stay in their little zone, and then grab you. And those guys would always give me a shout out whenever they were right behind me. So I thought that was kind of interesting. The Separation Wall was interesting too. Sometimes it’s interesting just to see what’s really going on. Because, god, the press lies so much, you know? I think it depends on who owns the publication. They’re going to want to tell a certain story. Sometimes it’s just nice to see things for yourself. I had a book come out a few weeks after 9/11. And, of course, nobody came to my book release party. Except for, suddenly, the whole place filled up. And I’m like, ‘Who are you people? I’ve never seen any of you before.’ And they’re like, ‘We’re from OSHA.’ And I’m like, ‘Well, why aren’t you down at the World Trade Center?’ And he says, ‘Giuliani locked us out.’ And he locked them out because the air was unsafe. The air was unsafe on Wall Street. And so they didn’t want any kind of reports coming out that the air was unsafe, because they wanted people down there, without masks, so they could keep Wall Street open. Which is horrifying to me because now those people have lung cancer and everything else. Any company in America would have given them free masks. They would have fallen all over themselves to do it. Just to have that image of people walking around downtown on Wall Street just three blocks away, and then trying to tell them it’s safe there. I’d rather have an image of people walking around with masks on Wall Street and being safe then all those people you know really damaging themselves just to keep the image up. But I mean isn’t there something inherently wrong with a country that can’t shut down for two weeks you know to preserve the life of the people that work in that area?

Ron English: The Berlin wall was interesting because there was this group of East Germans that were sitting, protesting. The wall is on the side of East Germany—or it was. So they can actually capture you if you’re within like 10 or 15 feet of the wall. They measured it out and they were, you know, camped there. They were there doing an ongoing protest. I painted for about a week on the wall. And they would sit and watch, because the East German authorities were trying to catch me. So I would be so absorbed in my painting. What they would do is come around the wall and quietly tried to walk up and, you know, stay in their little zone, and then grab you. And those guys would always give me a shout out whenever they were right behind me. So I thought that was kind of interesting. The Separation Wall was interesting too. Sometimes it’s interesting just to see what’s really going on. Because, god, the press lies so much, you know? I think it depends on who owns the publication. They’re going to want to tell a certain story. Sometimes it’s just nice to see things for yourself. I had a book come out a few weeks after 9/11. And, of course, nobody came to my book release party. Except for, suddenly, the whole place filled up. And I’m like, ‘Who are you people? I’ve never seen any of you before.’ And they’re like, ‘We’re from OSHA.’ And I’m like, ‘Well, why aren’t you down at the World Trade Center?’ And he says, ‘Giuliani locked us out.’ And he locked them out because the air was unsafe. The air was unsafe on Wall Street. And so they didn’t want any kind of reports coming out that the air was unsafe, because they wanted people down there, without masks, so they could keep Wall Street open. Which is horrifying to me because now those people have lung cancer and everything else. Any company in America would have given them free masks. They would have fallen all over themselves to do it. Just to have that image of people walking around downtown on Wall Street just three blocks away, and then trying to tell them it’s safe there. I’d rather have an image of people walking around with masks on Wall Street and being safe then all those people you know really damaging themselves just to keep the image up. But I mean isn’t there something inherently wrong with a country that can’t shut down for two weeks you know to preserve the life of the people that work in that area?

The Rumpus: Yeah, and it’s even stranger that they can be outraged that someone would do such harm to us, and then not actively try to prevent further harm. It’s strange and senseless.

Ron English: Right, right.

The Rumpus: I’d really love to hear if there’s a project that you’ve done, that I haven’t mentioned, that really meant a lot to you and really seemed like something you’re uniquely proud of.

Ron English: I guess there’s a lot of things. I remember one time I did a thing with the Guggenheim Children’s Fund. They sent me up to the South Bronx. So I hooked up with a bunch of pretty much disenfranchised kids. And we did this big billboard together. And I think that was really interesting because it’s not like your just giving them some money or something. You’re giving them this kind of power. I mean, the billboard is on their fucking building, you know, and there’s nothing they can do about it because they don’t own the building. The guy lives in Florida who owns the building. It shows them that you can actually do something. I think that meant a lot to those kids.

Ron English: I guess there’s a lot of things. I remember one time I did a thing with the Guggenheim Children’s Fund. They sent me up to the South Bronx. So I hooked up with a bunch of pretty much disenfranchised kids. And we did this big billboard together. And I think that was really interesting because it’s not like your just giving them some money or something. You’re giving them this kind of power. I mean, the billboard is on their fucking building, you know, and there’s nothing they can do about it because they don’t own the building. The guy lives in Florida who owns the building. It shows them that you can actually do something. I think that meant a lot to those kids.

The Rumpus: I’m so grateful that you took the time to speak with us.

Ron English: Thank you very much. That was great.

One response

I’ve always loved Ron’s impish reasoning. It feels like I’m talking to myself or someone very close to me — almost like a thought that races across my mind as I pass some absurd sign or whatever. Ron’s work makes me happy. For more on Ron, see the short film by Pedro Carvajal, which won the Media Literacy Award at the Media That Matters Film Festival. (Full disclosure, I work for Arts Engine, the producers of Media That Matters.)

POPAGANDA: THE ART & SUBVERSION OF RON ENGLISH

http://www.mediathatmattersfest.org/4/index.php?id=16

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment, or log in if you’re already a paid subscriber.