A Review of Dan Albergotti’s The Boatloads

A Review of Dan Albergotti’s The Boatloads

I have a special place in my heart for literature that juxtaposes the sacred and profane, that challenges perhaps the most successful meme ever to spring from the human brain: the belief that God is unwaveringly good.

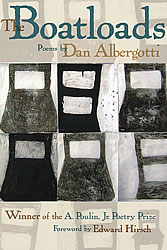

That’s the matter at the heart of Dan Albergotti’s first collection of poems, The Boatloads, winner of the 2007 A. Poulin Jr. Poetry Prize. The one constant in The Boatloads is doubt—doubt about God’s benevolence, about His existence, about the speaker’s worthiness of the blessings he has received—and in a world where certainty is fleeting, doubt plays an increasingly pivotal role.

Which is not to say that Albergotti isn’t searching for the transcendent in the universe. It’s in the clash between the sacred and the profane where he most often finds it. For instance, the opening poem, “Vestibule,” reflects on the speaker’s experience of sex in a university chapel. He wants to thank his partner, not so much for giving him a winning story, but “for the truth of it. / For knowing that the heart is holy even when / our own hearts were so frail and callow.” His speaker is a pilgrim much as Dante was, looking for guidance through a darkened wood. Even the direct statement, “What I know is what is sacred,” is undercut by the line that follows, the plea to the “Lord of this other world, let me recall that night,” as though the speaker really isn’t sure of what is sacred on his own, as though he needs permission from another to recognize the superlative.

“Song 246” takes us in a completely different direction. There’s no transcendence here, unless it’s transcendent pain. The poem takes on the notion of a loving, omnipotent God who allows atrocity:

What song could there be in the filthy basement

where the small boy is chained to a beam,his mouth gagged with an athletic sock?

What song there on this third morningWhile his parents keep putting posters of his face

on light poles through the city?

There’s no subtlety here, but when it comes to these sort of questions, subtlety would be inappropriate. There are evil people in the world, and sometimes they do horrible things to innocents, and to elide that with wordplay would be dishonest. Albergotti’s choice to have the kidnapper hum the Kool and the Gang party anthem, “Celebration,” while sharpening the kitchen knife just adds to the terror. There’s no salvation for the child, and no escape for the reader.

In the second section of The Boatloads, Albergotti occasionally assumes voices of characters from the Old Testament. Cain justifies his actions in “Testimony,” unicorns commit suicide on Noah’s Ark in “When the World Was Only Ocean,” and in “Book of the Father,” the OT narrator revives and updates the story of Abraham, patriarch of three of the world’s major religions. These poems undercut our received views of the characters involved: Cain uses God’s approval of Abel’s blood sacrifice to claim he was only acting the way God created him to act; it’s the serpents on the Ark who drive the unicorns to suicide; and Abraham is “In the tank with Ariel Sharon, in the studio with Jerry Falwell, in the cockpit with Mohammed Atta.”

In the second section of The Boatloads, Albergotti occasionally assumes voices of characters from the Old Testament. Cain justifies his actions in “Testimony,” unicorns commit suicide on Noah’s Ark in “When the World Was Only Ocean,” and in “Book of the Father,” the OT narrator revives and updates the story of Abraham, patriarch of three of the world’s major religions. These poems undercut our received views of the characters involved: Cain uses God’s approval of Abel’s blood sacrifice to claim he was only acting the way God created him to act; it’s the serpents on the Ark who drive the unicorns to suicide; and Abraham is “In the tank with Ariel Sharon, in the studio with Jerry Falwell, in the cockpit with Mohammed Atta.”

In “The Safe World,” near the end of the section, Albergotti captures the coincidences that some believers interpret as miracles, guardian angel moments:

…And later,

you carelessly dropped your right shoe

before you could get your foot into it,

and the impact from the hardwood floor

ejected the black widow from the interior.

And then you spent ten minutes considering

the perfect symmetry of the red hourglass

on the spider’s belly. So you arrived

at the intersection ten minutes later

than you otherwise would have, when a bus

plowed through a red light (and two cars)

its driver dead of a massive heart attack

at fifty two.

We generally hear claims of God-as-lifesaver in the aftermath of tragedies—plane crashes, earthquakes, hurricanes—but it’s not unusual for believers to find divine intervention in everyday luck. It’s not even all that odd for cynics to try to find logic in coincidence—I think that’s what Albergotti is getting at when he tells the reader, “You’ll take the time to think / about your grandfather and the German gas / your father’s stumble with the cannon shell.” Looking for logic in luck is, if not wholly reasonable, at least understandable; but the poem refuses to provide agency in these examples—there is no guardian angel knocking the shoe out of your hand, no divine presence steadying your father just before he falls on a cannon shell. It just happens that way today, and on another day, it might not.

A companion piece to “The Safe World” might be “Poem in which God Does Not Appear.” Instead of focusing on what might happen, Albergotti gives only the barest details of what did happen: “The sky becoming / everything beneath it, blood black against a dark shirt, / the mother’s heart, the mother’s beating heart,” and the father in the poem, his final words Oh my lord, my absent God. It’s the inclusion of the word “absent” that carries so much punch here, the open acknowledgement that, if God is responsible for saving people, He’s also responsible for letting them die, that the one who can see all things can also choose to ignore all things.

Perhaps the most agnostic poem in The Boatloads is “The Last Song of the One True God.” The idea of the poem is that this is a song that no one can truly hear, that we can only see “Ideas of notes… / like shadows on a flat screen,” perhaps on the wall of Plato’s cave. But the final comparison is the most telling, I think: “It’s like the tiny white flowers that bloom / on the head of the Korean Buddha,” Albergotti writes, and it’s telling that after evoking the religions that come out of the Middle East—“It’s like / the mumbled prayers of the prophet / in the wilderness,”—and Hinduism, Albergotti finishes with this comparison to the Korean Buddha, because while there is no question that Buddhism is a powerful religious force, it also lacks a God or gods to whom worship is rendered. It has scripture, but a completely different sense of the divine from that found in most other major religions—divinity is a state of enlightenment that practitioners hope to achieve. It’s a signal that while there may be something out there to worship, there are no guarantees as to what form it will take, or if it’s even listening when we call.