Reading and Teaching Proust Was a Neuroscientist

I have always wanted to teach a semester of freshman English using a single text, moving students via rich allusions out beyond it for further reading according to their individual interests. Proust Was a Neuroscientist by Jonah Lehrer is a collection of essays linking contemporary findings in neuroscience with visionary knowledge dreamed up by writers and artists a hundred years ago. Concepts like Walt Whitman’s poetic “body electric” and Virginia Woolf’s psychological “stream of consciousness” are proven to have physical origins in our brains and bodies.

Last fall, I created a whole course around the book at California College of the Arts and it worked great! Students found the essays difficult in just the way you would hope: They grumbled, but in final evaluations had to admit they had learned a lot. As one student put it, “I’m kind of a big fan of this class… I’d be tempted to kill myself if I were handed yet another book of fiction and told to write about it.”

Proust Was a Neuroscientist is brilliant in the way it makes connections across the formerly rigid boundary between art and science. CCA is a school of art, architecture, design, and writing, so Lehrer’s essay on Cezanne called “The Process of Sight” was directly pertinent. Another student felt that the book “introduced interesting concepts of science that were unexpected yet relevant to the art context.” Lehrer is amazingly able to instruct the reader in the anatomy of the brain while offering insight into how we are able to read and interpret literature, art, photography, and music.

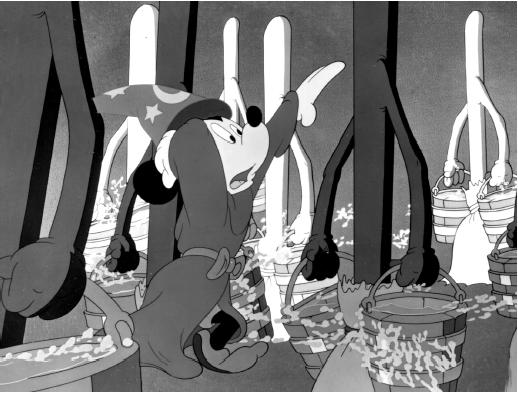

“The Source of Music” talks about T. S. Eliot and Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring” and led to discussions of what Lehrer calls “the birth of dissonance.” We read excerpts from Eliot’s The Waste Land, watched the section of the Disney classic Fantasia that uses “Rite of Spring” as the soundtrack. Students then produced audio essays set to “apocalyptic” contemporary music.

This all took place in the midst of our national election, before the results were in, when there was a feeling we might be headed for the end of the world. Listening to musical renditions of our collective fear felt cathartic; writing narrations that placed the music in context of Lehrer’s dissonance theories provided liberating historical perspective. “Nothing is sacred. Nature is noise. Music is nothing but a sliver of sound that we have learned how to hear.”

But who’s in charge? Lehrer asks, “Is life just a fancy machine? Are we nothing but chemicals and instincts adrift in an indifferent universe?” Free will versus fate is a favorite debate for the college classroom and readily feeds late-night dorm room philosophy. Lehrer analyzes natural selection versus intelligent design and dissects the biology of freedom via George Eliot and Middlemarch, along the way providing a useful introduction to the work of Kant and Darwin. The book is ingenious in the way it references so many thinkers from the realms of philosophy, art, literature, psychology, and sociology, including neuroscientist Fernando Nottebohm who blessedly posits that the mind can remake itself anew even as we age. (This notion has been popularized recently in the PBS series hosted by Peter Coyote on the brain and “plasticity.”)

But who’s in charge? Lehrer asks, “Is life just a fancy machine? Are we nothing but chemicals and instincts adrift in an indifferent universe?” Free will versus fate is a favorite debate for the college classroom and readily feeds late-night dorm room philosophy. Lehrer analyzes natural selection versus intelligent design and dissects the biology of freedom via George Eliot and Middlemarch, along the way providing a useful introduction to the work of Kant and Darwin. The book is ingenious in the way it references so many thinkers from the realms of philosophy, art, literature, psychology, and sociology, including neuroscientist Fernando Nottebohm who blessedly posits that the mind can remake itself anew even as we age. (This notion has been popularized recently in the PBS series hosted by Peter Coyote on the brain and “plasticity.”)

Art students tend to be active, sensual, tactile people, so they appreciated unusual assignments like the audio essay and a visual essay that included thorough-yet-concise captions on “the cliché of representation” and “art’s pseudo-scientific fidelity to reality,” inspired by Lehrer’s Cezanne piece. We contemplated the limits of light, read Baudelaire’s 1859 critique “On Photography,” and bent our minds around Gestalt theory and optical illusions. Thus, the engaged student reports, “What I have learned in your course has bled into my other courses (and personal life).”

The title piece on Proust lent itself nicely to creative writing and personal essays, with the trick being to access forgotten memories. Proust’s famous madeleine caused an involuntary memory, triggered by the sense of taste and smell, “the most nostalgic sense.” Yes, we ate madeleines in class, and read excerpts from Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (a.k.a. Remembrance of Things Past – Lehrer explains the reasons for the various translations of the title). Apparently, we do not only reach wisdom via the intellect. It is a labour in vain to attempt to recapture it: all the efforts of our intellect must prove futile, Proust wrote. The past is hidden somewhere outside the realm, beyond the reach of intellect, in some material object (in the sensation which that material object will give us) which we do not suspect.

Given that CCA students are in the business of creating material objects designed to elicit sensations beyond intellect (i.e. art), Proust’s ideas here have clear relevance. Students are taught all their young lives to be reasoned and logical people; they arrive at art school and have to be retrained as emotional and imaginative creators, a task sometimes best achieved by unreasonable, illogical methods.

Are we crazy? “Science is not the only path to knowledge,” according to the blurb of Proust Was a Neuroscientist. “When it comes to understanding the brain, art got there first.” Lehrer asks us to read Virginia Woolf and Gertrude Stein. According to Lehrer, Stein’s major literary discovery was that, no matter how hard she tried to strip language of meaning, the brain’s “desperate neuronal search for patterns” trumped her. We studied Tender Buttons, initially incomprehensible like so much of Stein’s writing. First, just let it wash over you and see how that feels. Then apply your brain and analyze meanings of individual words plus words in relation with one another; in the midst of nonsense, meaning arises. Students were assigned to write “nonsense essays,” something they laughed at, thinking it would be easy, only to learn how difficult it is to turn off the brain’s basic impulse to make meaning.

About Oakland, CA, where our campus is located, Stein famously said, “There is no there there.” Lehrer shows that neuroscience agrees: “The head holds a raucous parliament of cells that endlessly debate what sensations and feelings should become conscious. These neurons are distributed all across the brain, and their firing unfolds over time. This means that the mind is not a place, it is a process.”

Lehrer sees Virginia Woolf as having offered an alternative to the hardnosed scientific materialism of her time. “Woolf’s art searched for whatever held us together. What she found was the self, the ‘essential thing,’” Lehrer writes. She “wanted to expose our ineffability, to show us that we are ‘like a butterfly’s wing… clamped together with bolts of iron.’” And who hasn’t felt that way, as finals loom, and family calls, and we face our future not knowing what it will hold? “Woolf realized that the self emerges via the act of attention. We bind together our sensory parts by experiencing them from a particular point of view.”

Lehrer sees Virginia Woolf as having offered an alternative to the hardnosed scientific materialism of her time. “Woolf’s art searched for whatever held us together. What she found was the self, the ‘essential thing,’” Lehrer writes. She “wanted to expose our ineffability, to show us that we are ‘like a butterfly’s wing… clamped together with bolts of iron.’” And who hasn’t felt that way, as finals loom, and family calls, and we face our future not knowing what it will hold? “Woolf realized that the self emerges via the act of attention. We bind together our sensory parts by experiencing them from a particular point of view.”

With what magnificent vitality the atoms of my attention disperse, Woolf wrote, and create a richer, a stronger, a more complicated world in which I am called upon to act my part.

We are all called upon to act our parts. I am an English professor. With the help of Jonah Lehrer’s clearly written and comprehensive book, I did what I am compelled to do: teach students how to read, write, and think for themselves, whoever they may be.

**

See Also: Anti-War Poetry and the Oxymoron of Liberal Fathers

2 responses

wish I had a class like Marianne’s when I was studying for my business degree as an adult student – I missed out! I have attended Marianne’s writing workshops to attend to grief, growth and other “G” things. Recommend her! Check Book Passages newsletters from to time and sign up when one is scheduled.

Thanks Marianne for making my brain cells hum – yet again.

I want to read the book, take the course, and complete the projects, all for the thrill of trajectory into a new dimension of meaningful metaphor. Marianne, thank you for introducing Lehrer’s book and for continuing to empower us to read, write and explore our temporal and literary worlds.

Diane, a student, fan, and lifelong friend.

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment.