There is a peculiar quality to “A Journey Through Darkness,” Daphne Merkin’s memoir of chronic depression published this week in the Times Magazine. Her intimate account of lifelong struggle with the disease, centered on her latest stint in a Manhattan psychiatric facility in 2008, evokes the perspective of a highly intelligent, sensitive, deeply troubled soul. Even if the trappings are familiar from numerous other written explorations of the subject, her story seems to shed light on the dark terrain of mental illness by way of an intense personal account.

But an intriguing question sits at the margins: Who, exactly, is telling this story?

Merkin is a skilled writer with a clear command of technique. Memory has been and always will be a writer’s imperfect tool. But something about her in-depth reflection feels a little too… artful. It begins and ends with the bright imagery of ocean beaches, neatly bookending the tale of her latest debilitating episode. There is elevated language and metaphor all over the place. “Soggy as my brain is from being wrenched off a slew of antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications in the last 10 days, I reach for a Coleridgian suspension of disbelief, ignoring the roar of traffic and summoning up the sound of breaking waves,” she writes of an attempt at mental escape from the hospital grounds.

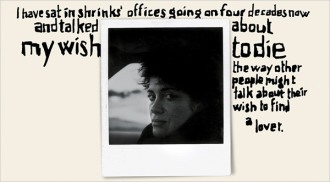

And: “Depression — the thick black paste of it, the muck of bleakness — was nothing new to me.”

And: “When I was awake (the few hours that I was), I felt a kind of lethal fatigue, as if I were swimming through tar.”

And: “I felt as if I were being wished bon voyage over and over again, perennially about to leave on a trip that never happened.”

And: “In truth there was more uncharted time than not, especially for the depressives — great swaths of white space that wrapped themselves around the day, creating an undertow of lassitude.”

As with that last flourish, there are other assertions of truth telling. Which is not to say her story is untruthful.

Merkin has in the past written publicly about her experience with depression, and to her credit here she points at a vexing problem of distinction — it’s almost as if she’s questioning her own reliability as narrator:

Whatever fantasies I once harbored about the haven-like possibilities of a psychiatric facility or the promise of a definitive, once-and-for-all cure were shattered by my last stay 15 years earlier. I had written about the experience, musing on the gap between the alternately idealized and diabolical image of mental hospitals versus the more banal bureaucratic reality. I discussed the continued stigma attached to going public with the experience of depression, but all this had been expressed by the writer in me rather than the patient, and it seemed to me that part of the appeal of the article was the impression it gave that my hospital days were behind me. It would be a betrayal of my literary persona, if nothing else, to go back into a psychiatric unit.

Certainly a writer aims to convey an experience as vividly as possible. Merkin’s work gives the sense she is deeply invested in sorting out her experience, both for herself and for her audience. (Having that audience, as she seems to know, could be a particularly complicating factor.) Yet as carefully constructed as it is, something about her story feels distinctly blurred.

Maybe it’s of a piece with a vexing question about the treatment of mental illness, one I’ve often puzzled over when concerned for people I know who are afflicted: Where, exactly, is the line between the physical and the psychological?

In that respect Merkin’s deliberate prose does little to help us out of the dark.

One response

One of the more honest portrayals of depression, or at least of the self-loathing that characterizes certain forms, is DFW’s short story “The Depressed Person.†I regret that I only discovered it after DFW’s death.

Be warned, it’s a brutal account:

http://www.harpers.org/archive/1998/01/0059425

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment.