“…Beauty is often considered suspect based on the lingering premise that it is radically conservative and reactionary, and that the strategies of visual appeal used by the mass media can be seen as one of the ways that authentic experience is transformed into mediated experience and false consciousness.”

Zak Smith: Your paintings are beautiful. What’s up with that? Don’t you know this is 2009 and you’re supposed to make paintings that are ugly or, at the very least, boring, in order to highlight that the only thing that matters is the choice of subject? These paintings aren’t beautiful for like three seconds, either, I could look at them for a very long time, they’re beautiful for several hours at a time. Didn’t you get the memo? Contemporary art in 2009 is only allowed to look good in the interior-design sense. Deep looking is discouraged; why have you taken the left-hand path and attempted to radically absorb the viewer into your little universes?

Gordon Terry: I think I’ll answer these two questions at once: There’s a careerist voice in my head that always nags me about this. But my belief that humans approach ideas through materials, through the physical, always wins out in the end. Ultimately, there are a lot of theoretical arguments I could make to prop up my fixation on the aesthetic experience, form, and the sensuality of materials, but honestly it comes down to the fact that it’s my first impulse.

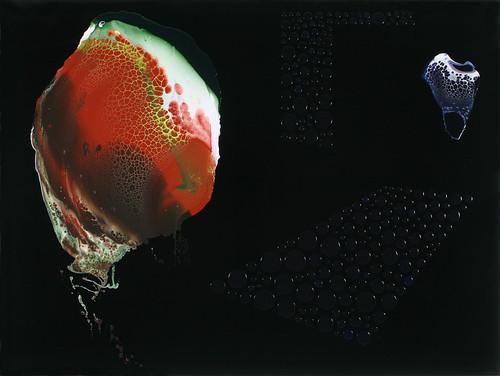

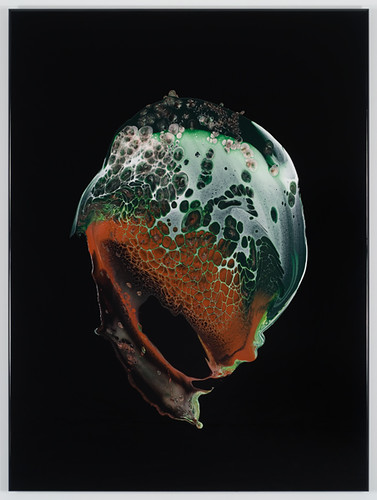

One of the ideas about physical form that has become very important to me is the notion of immanence, or the subtle difference between immanence and transcendence. I’m fascinated by the potential for objects to be infused with a sense of the numinous, of the “wholly other.” This is essentially the metaphysics of immanence–the otherworldly, or the sacred existing and acting within the physical world–as opposed to transcendence, where an unseen reality exists in a realm above and unconnected to the physical world. I also like to think about this dichotomy in terms of pagan and shamanic world views as opposed to gnostic, technophilic, and Judeo-Christian approaches to otherworldy content.

I’m glad you mention “radical absorption.” I totally think it’s one of the ideal responses to my work. The meaning of aesthetic experience can be, I think, characterized by Theodor Lipps‘ theory of empathy. In Lipps’ theory, aesthetic enjoyment requires the apperception of a sensuous object separate from the viewer, who empathizes life into an object. Forms hold their beauty and life only through the vital feeling that we in some mysterious manner project into them.

This is a very humanist perspective which I think touches in some way on my fixation with beauty…

I think a lot about how and why the idea of beauty has largely been removed from critical discourse, particularly as it relates to visual culture. To be completely reductive, I think beauty is often considered suspect based on the lingering premise that it is radically conservative and reactionary, and that the strategies of visual appeal used by the mass media can be seen as one of the ways that authentic experience is transformed into mediated experience and false consciousness.

This is complicated to me because the idea of “authentic experience” as a premium is very humanist and leaves a lot of room for meaningful aesthetic experience. And I actually really admire a lot of the thinkers that I associate with this type of criticism. Particularly after reading Breaking Open the Head, by Daniel Pinchbeck, who uses Benjamin and Adorno very convincingly to argue that both psychedelic experience and the shamanic world view are relevant to our state of cultural crisis.

But this is just one excuse to be suspicious of beauty–maybe just one way it manifested in the 20th Century. I think there’s been a long-standing, Northern European prejudice against color (which I’ll loosely connect to the discussion of “beauty”) going much further back. I recently saw Michael Taussig lecture about a new book he’s writing about color; color as it was historically exploited, marketed and experienced by colonial European powers. He told a story about how Northern Europeans weren’t really exposed to bright colors until the indigo trade reached full tilt. When brightly colored dyes and textiles started to come on the market they were simultaneously attracted to and repulsed by them. Attracted sensually, but repulsed by the association with primitives and savages, and all the sexuality and godlessness associated with them. Essentially, his argument is that this is where the prejudice against color starts, where the idea that restrained, muted, unsaturated color equals sophistication, refinement, and taste; whereas vibrant, saturated, high value colors equal garish, unrefined, lo-brow and childish tastelessness.

Smith: Back in the day, old abstract painters used to leave their paintings untitled, or give them some sort of neutral title, in order to emphasize that everything the viewer needed to know was in the picture. Your titles, on the other hand, are long and topical, like “Often Originating With Intelligent Forces At Present Unknown To Us,” that seem to be almost jokes.

3 responses

Zak: Were you at the Dennis Cooper reading at Skylight Books? Congratulations on the upcoming publication and book tour!

Ken:

Yes indeed I was.

And thank you!

Zak,

Nice job. Without eliding or jiving you let through the music of the spheres.

Erik

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment, or log in if you’re already a paid subscriber.