It’s almost like you’re saying to the viewer: “Ok, buddy, you really need a title? Here’s a title. See, it’s useless. Go look at the painting some more.” Am I just projecting, or is this maybe part of your strategy?

Terry: I’m glad you said the word, projection. My titling strategy started out as a way to underscore the tendency for abstraction (or anything for that matter) to function as an empty vessel into which content is projected by the viewer. In this sense, the titles are jokes. But what I like about the idea of the joke is how a joke can dovetail with its opposite. So in this sense, they are all completely serious. Usually, they derive from whatever I happen to be reading at the time I am making the work, often fairly crackpot stuff (and some not-so)–things like paranormal phenomena, psychedelia, hermetic occultism, drugs, rock, history, theoretical physics, prophecy, the I-Ching, and the Mayan calendar. These interests consume me and inform my world view to such a degree, that I think they end up in the work on some level. But maybe I should just admit my secret desire to be an occult investigator!

Smith: Although critics have picked up on the fact that the images and titles refer to things like psychedelia and parapsychology and high culture, your work itself seems mostly to take the viewer to a psychological realm where the whorls and incidents that come out of the process of painting become a sort of referent-free meditative psychological space. This confuses some people, I think. My impression is that part of what you’re implying is that psychedelic art and ideas about ghosts and philosophical ideas and literature are in themselves all attempts to explore psychological space–just like your paintings. Does that make sense?

Terry: Totally. Our existence is a continuum between the observer and the observed, thought and experience. I’m interested in experiences that dissolve boundaries and categories. And I’m interested in making things that can accommodate contradictory positions. Almost all we perceive is projection, so the exploration of psychological space, and how that manifests the observed world, and how the observed world we create is the objectification of our collective ideologies, fascinates me.

Last year my wife played me a recording of Duchamp giving a lecture in Houston where he describes “the art coefficient,” an idea that resonates with the disconnect you point out. He defines the art coefficient as the almost mathematical relation between the” unexpressed but intended and the unintentionally expressed.”

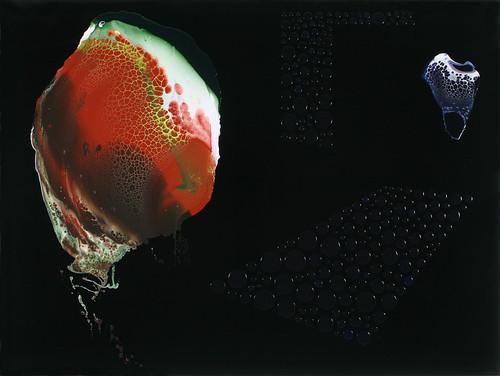

Smith: A Jackson Pollock painting is, among many other things, an illustration of movements and actions taken by Jackson Pollock. This is true for most abstract artists of his era until the “hard-edge” masking-tape painters took over and erased all evidence that a painter had touched the painting. Your paintings fit neither model. They look like you set some chemical and physical reactions going and just let them blossom–like you grew them or presided over them. A lot of people have made stupid analogies comparing Pollock to a cowboy. Would you make a stupid analogy comparing yourself to a scientist?

Terry: Yes, but of the crackpot, visionary type. You know, the kind that analyzes node lengthening in crop circles, researches free-energy technology or crystal skulls, or tries to prove that ice crystals become more organized when exposed to positive energy, or that meditation decreases world violence, or that the delayed choice experiment demonstrates a causal connection between consciousness and external reality. A writer once called me “a botanist of the imaginal” who “breeds and archives hallucinogenic dream portals.” I have no problem with that.

Smith: A lot of these remind me of deepened, strengthened versions of the aesthetic from sci-fi book covers from the 60s and 70s. The kind that would occasionally get re-sold to publishers as covers for philosophy textbooks. Do you look at them actively? Or are they just sort of a thing you see incidentally now and again and go “Yeah, that’s nice”? Or do you disagree entirely and have no idea what I’m talking about?

Terry: I thought this would be an easy: “Yes. I look at them actively and often and they totally influence me.” I love sci-fi cover art, I’m an avid sci-fi fan and in my teens I was obsessed with Heavy Metal and Epic Illustrated. Michael Moorcock, the creator of Elric of Melnibone, the albino warrior prince, with the soul sucking black blade “Stormbringer,” was also a fave. I also teach drawing at NYU and usually pull out a Boris Vallejo book or two. But I can’t honestly say that I actively look at book covers from the 60’s and the 70’s. I used to very casually collect (or accumulate) them and at that time they found their way more directly into my work. I remember wishing I had made Glenn Brown‘s paintings in the mid 90’s. But now, I think it’s more accurate to say they form the background bass drone of my aesthetic. I say this because I know the covers you refer to were formative for me, but I don’t have a list of the “great” ones at my disposal. I guess you gave me an idea for a more rigorous area of research!

Terry: I thought this would be an easy: “Yes. I look at them actively and often and they totally influence me.” I love sci-fi cover art, I’m an avid sci-fi fan and in my teens I was obsessed with Heavy Metal and Epic Illustrated. Michael Moorcock, the creator of Elric of Melnibone, the albino warrior prince, with the soul sucking black blade “Stormbringer,” was also a fave. I also teach drawing at NYU and usually pull out a Boris Vallejo book or two. But I can’t honestly say that I actively look at book covers from the 60’s and the 70’s. I used to very casually collect (or accumulate) them and at that time they found their way more directly into my work. I remember wishing I had made Glenn Brown‘s paintings in the mid 90’s. But now, I think it’s more accurate to say they form the background bass drone of my aesthetic. I say this because I know the covers you refer to were formative for me, but I don’t have a list of the “great” ones at my disposal. I guess you gave me an idea for a more rigorous area of research!

Smith: This work is literally experimental, in the sense that you had to invent the techniques you use from scratch, I presume. Are you an “experimental” artist?

Terry: Experimenting with materials in order to arrive at ideas is definitely part of my process. A lot of my experimenting has to do with replicating organic patterns of growth and the self-organizing properties of nature. I get off on the giddy surprise I feel when I set a process in motion and it results in an effect or a space that I didn’t intend and have never made. Most recently, I started experimenting with altering the viscosity of my medium through temperature manipulation and the result was a field of separated colors, reminiscent of Vallejo’s treatment of fairy wings and the “chrysanthemum pattern” frequently experienced at the onset of a DMT trip.

I have had to invent a lot of my techniques, but they aren’t without precedent. Strangely, even though I might be considered a process artist by many, I consider process secondary to my other concerns. Am I an “experimental artist”? That seems like a very historical term, and it’s not necessarily how I would identify myself, but I’m more comfortable with that label than I am with “process artist.”

Smith: What’s the ideal situation to see art in, in your opinion?

Terry: That’s an interesting question because the general vibe or atmosphere of the art world is not really conducive to a good time or inspired viewing. My thinking is that ideally, an art viewer in some way psychologically or conceptually recapitulates the creative process that the artist went through in making a piece when they view it. There’s something very constrictive about the art world, something that works against the drive to be a free spirit that can get in the way of this process. Museums and galleries often aren’t the most inspiring places to be in or to view art in. But they do allow for sustained, relatively unmediated looking and experience. I’d like to think that Burning Man or some other freak friendly venue would be more ideal for viewing art, but my hunch is this isn’t the case. There’s ample opportunity to be engulfed by spectacle in this world, so I’d say there’s still some value in quiet, solitary looking in the white box.

Smith: Can you give us a name of some artists that we have heard of that influenced you that we might not realize have influenced you? In what way?

Terry: I never like to answer this question. But as an experiment I’ll list the first artists who pop in my head, in no particular order: Harry Smith, Alfred Jensen, Joseph Albers, Ernst Fuchs, John Cage, Olivier Mosset, Nicki de St. Phalle, Rudolph Stingel, Agnes Martin, Emma Kuntz, Hilma Af Klint, Mondrian, Malevich, Aleister Crowley, Jim Lambie, Robert Smithson, Andreas Gursky, Gary Hume, Joan Mitchell, Gerhard Richter, David Bowie, Sol Lewitt, Ed Ruscha, Carol Bove, Sigmar Polke, Sean Landers, Sarah Morris.

Smith: I think most art critics have a very difficult time writing about abstract art in a compelling way and that, therefore, they write about it less, and that therefore, there’s an illusion that it’s less “relevant” than whatever the latest thing the trust-fund kids are paying their assistants to do this week. Have you run into this bias?

Terry: Sure. But I don’t think it’s always such a straightforward bias. Actually, abstraction seems to be having a fashion moment right now and is getting a good amount of critical attention. Just a slightly different looking abstraction than what I’m doing. There are a lot of parallels between my work and a painter like Joe Bradley, for instance, but on the surface our work looks very different. I think painting, particularly abstract painting, has had a tough time in the critical discourse ever since AbEx was superseded by Pop and Minimalism. I think there’s a lingering, unexamined mind-set that painting is inherently conservative and merely formal, that it’s naive and not “rigorous,” so it gets left out of the discourse (but left to dominate the market which fuels the fire even more). This distinction seems conservative in itself to me, and outmoded. Even the most de-materialized, conceptual practice has a formal dimension.

Smith: How much control do you have over any of these images as they dry and form? Can you change them dramatically once the paint goes down or is it set after the initial shapes are made?

Terry: I have a lot of control over the types of processes I set in motion, and the resulting effects. And I frequently manipulate the shape while wet. But there is an aspect of chance inherent to all my procedures. Once the paint is down and setting, it’s down. All the elements are in themselves one-shot deals. But, I don’t actually paint on any of the cast acrylic surfaces that are the grounds for my paintings. I work on a large glass work table suspended on hydraulic jacks that allow me to tilt the table on both an x and a y axis in order to exploit gravitational effects. I also use other hands-off techniques like pressurized air bursts, wet on wet spreading, etc. to manipulate the paint. This is where I “breed” the forms; from there they are removed from the glass, edited, inventoried, and then they are applied to my surfaces. I have a lot of paint elements to pick and choose from as I work on a painting. Everything is transferred, even the gestural, Pollock-esque splatter fields, bit by bit. Sometimes, I’ll approximate the same form over and over until I have the most idealized version for the final piece.

Terry: I have a lot of control over the types of processes I set in motion, and the resulting effects. And I frequently manipulate the shape while wet. But there is an aspect of chance inherent to all my procedures. Once the paint is down and setting, it’s down. All the elements are in themselves one-shot deals. But, I don’t actually paint on any of the cast acrylic surfaces that are the grounds for my paintings. I work on a large glass work table suspended on hydraulic jacks that allow me to tilt the table on both an x and a y axis in order to exploit gravitational effects. I also use other hands-off techniques like pressurized air bursts, wet on wet spreading, etc. to manipulate the paint. This is where I “breed” the forms; from there they are removed from the glass, edited, inventoried, and then they are applied to my surfaces. I have a lot of paint elements to pick and choose from as I work on a painting. Everything is transferred, even the gestural, Pollock-esque splatter fields, bit by bit. Sometimes, I’ll approximate the same form over and over until I have the most idealized version for the final piece.

Smith: I’ve noticed that people love your work. As in, I go “Hey, I’m doing an interview with this guy” and turn the screen around and they go “Ooooh, that’s great!” Have you noticed that the viewing public is viscerally taken by these images?

Terry: I’ve seen people lick my paintings and spontaneously make out in front of them. Babies love them too.

Smith: When’s your next show, project, etc?

Terry: I’m in a show curated by Joe Wolin, called “In the Splinter of the Mind’s Eye,” at the Philip Slein Gallery in St. Louis. It’s a group show about work that’s influenced equally by sci-fi and gestural abstraction. I’m also going to be included in a survey book on psychedelic and visionary art published by the San Antonio Museum of Art. And most likely a show at ATM Gallery coming up later this year.

Smith: Your pictures remind me of, for example, the famous Hubble photo of the Eagle Claw Nebula, or Herzog’s recent movie about Antarctica, yet, at the same time, the paintings freeze these images into a form where I can look at them in much greater detail and with much deeper and richer color than you can see in the images they echo. Do you feel like people look this closely at paintings? Why go to all that extra effort?

Terry: Some people do, some people don’t. The references you make in your question are the types of things that inspire me to make paintings. I also have to be inspired by my paintings in order make them. And I look closely. I guess, in terms of audience, I’m the first critic my work has to make it through. So I don’t really have any choice but to go through the effort.

3 responses

Zak: Were you at the Dennis Cooper reading at Skylight Books? Congratulations on the upcoming publication and book tour!

Ken:

Yes indeed I was.

And thank you!

Zak,

Nice job. Without eliding or jiving you let through the music of the spheres.

Erik

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment.