The Lucky 13 Saloon in Brooklyn is papered with horror movie posters and painted with a fine layer of filmy grit. A mutilated Chuckie doll straddles a Jaegermeister spout from which bartenders in leather corsets pour shots for guys sporting shaggy goatees and pierced women with neon hair.

The Lucky 13 Saloon in Brooklyn is papered with horror movie posters and painted with a fine layer of filmy grit. A mutilated Chuckie doll straddles a Jaegermeister spout from which bartenders in leather corsets pour shots for guys sporting shaggy goatees and pierced women with neon hair.

Far from a tourist at the Saloon, I have had five, dead-serious dudes shred air guitars in a semi-circle around me at the bar’s karaoke night as I belted the lyrics to “Iron Man.” Sure, you can sing Journey at Lucky 13, but will you have the guts to after hearing the chubby guy in the Lamb of God T-shirt do a shrill, nearly perfect rendition of “Metal Health”? I weigh 110 pounds and none of that is muscle. For extra cash, I sell organic lettuce at the farmer’s market. But tell me I’m not metal while “The Number of the Beast” is playing and I will peel the skin from your eyes.

I love Slayer, Megadeath, Motorhead, Black Sabbath-and especially Iron Maiden. The music is complex enough to keep me interested and crafts unexpected artistry from rebellion. I like the misdirected censorship it invites, and the unexpected community that emerges whenever people flash the devil horns en masse. These days, an interest in hard music helps to cancel out my bright pink bike helmet and green hi-tops, but at a time when a 15-piece drum set, brutal shredding, and a cobwebbed ghoul named Eddie would have complimented my turbulent, disagreeable personality, I wanted nothing to do with heavy metal.

I love Slayer, Megadeath, Motorhead, Black Sabbath-and especially Iron Maiden. The music is complex enough to keep me interested and crafts unexpected artistry from rebellion. I like the misdirected censorship it invites, and the unexpected community that emerges whenever people flash the devil horns en masse. These days, an interest in hard music helps to cancel out my bright pink bike helmet and green hi-tops, but at a time when a 15-piece drum set, brutal shredding, and a cobwebbed ghoul named Eddie would have complimented my turbulent, disagreeable personality, I wanted nothing to do with heavy metal.

From the ages of 12 to 18, I was angry. My misbehavior wasn’t exceptional and it didn’t have an obvious catalyst (family was OK, no poverty, generally well treated), but the unpredictable mass of rage was there, in my house and at school, like a ghost with a penchant for slamming doors. I screamed a lot and kicked walls and smashed down the phone receiver when the person I was talking to pissed me off. Of course I smoked, drank and did some drugs—though I didn’t really enjoy them—and bragged about cursing at teachers, sex and random acts of vandalism, but this was because the fury had to come out, usually along with hot, shrill tears.

And yet despite my self-pity and my anti-social tendencies, rather than a Steve Vai Flying-V, I lugged a cello nearly my size to orchestra rehearsal, lessons, and chamber music practice several times a week—it may have been the only thing I did without complaint. Besides genuinely enjoying the music, I felt the instrument lent me a certain pathos and depth. I was that girl: buzz cut, nose ring, dressed in an oversized men’s work shirt, playing cello. It rounded out a fantasy of myself as eccentric and artistic. Playing quieted my mind and offered ample time to lick wounds and nurture feelings of righteous indignation. It also put me in contact with a lot of other kids who were starring in their own melodramas of adolescent torment.

Because the seating in orchestras is arranged so that you can see as many other players as possible, rehearsal stoked sexual tension. Many heated, hopeful relationships existed primarily through ongoing eye contact; the thirsty stares of 14-year-olds say more than most could hope to communicate verbally. The music that we all made together was emotional, romantic and seemed, to my ears, totally adult. The melodies and chord progressions of Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony (the cello section is swept up in the anticipatory theme) or Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet, where the basses and cellos rumble like an encroaching elephant army (the kind with murderous tusks, not some hoity Babars in bow ties), and the experience of making music together, all contributing to a sound much larger than any individual’s playing, was exciting. It felt like we were getting away with something akin to “borrowing” a parent’s car and sneaking off with a keg.

I was never a talented or driven soloist. This was a way to play music of a quality and complexity I wouldn’t have had the chops for without a hundred or so other musicians covering my ass. I played symphonies by Brahms, Beethoven, Schubert, Prokofiev and Tchaikovsky, though I didn’t listen exclusively to classical music in my free time. I liked Motown, some hip hop, and loved Liz Phair, but I hated the overt aggression and masculinity of heavy metal. My boyfriend had a dresser full of Cannibal Corpse t-shirts and knew every lyric on Tool’s Undertow, but I’d have none of it. We compromised with punk and ska and, occasionally, Stravinsky because, I’d argue, the audience rioted at the premiere of Rite of Spring (virgin sacrifice somehow didn’t strike me as a feminist issue). It’s surprising, considering how alien I felt in school and family, that I didn’t “get” heavy metal’s embrace of outsiders. Its irony was lost on me. But had I been able to tolerate or listen to what wasn’t immediately palatable, to appreciate difference and dark humor, I might not have felt so poisoned in the first place.

After the routine successes and disappointments of college, independent living in New York City and the natural ebb of teenage self-absorption, my edge is more butter knife than razor blade. But instead of lilting guitars and airy melodies, these days I’m after stories of mass graves and epic battles growled over the din of three guitars set to 11; songs about nothing you or anyone else on earth has ever experienced-mostly dying, usually after extended contact with fire, acid and venom. And it turns out I’m not the only mild-mannered professional who has gleaned a little edge and inspiration from heavy metal. In 2004, producers Scot McFadyen and Sam Dunn founded Banger Films and in 2005 released the documentary Metal: A Headbanger’s Journey. Dunn has a Masters degree in anthropology from the University of Toronto and their first film was designed to honor the history of heavy metal music and its fervent fan culture. In a recurring shot, we see Dunn at a show, covered in sweat and headbanging furiously, but there’s also footage of the producer reading quietly in the U of T library. The film’s combination of autobiographical and academic engagement with its subject suggest that Dunn is reconciling his own supposedly disparate passions.

After the routine successes and disappointments of college, independent living in New York City and the natural ebb of teenage self-absorption, my edge is more butter knife than razor blade. But instead of lilting guitars and airy melodies, these days I’m after stories of mass graves and epic battles growled over the din of three guitars set to 11; songs about nothing you or anyone else on earth has ever experienced-mostly dying, usually after extended contact with fire, acid and venom. And it turns out I’m not the only mild-mannered professional who has gleaned a little edge and inspiration from heavy metal. In 2004, producers Scot McFadyen and Sam Dunn founded Banger Films and in 2005 released the documentary Metal: A Headbanger’s Journey. Dunn has a Masters degree in anthropology from the University of Toronto and their first film was designed to honor the history of heavy metal music and its fervent fan culture. In a recurring shot, we see Dunn at a show, covered in sweat and headbanging furiously, but there’s also footage of the producer reading quietly in the U of T library. The film’s combination of autobiographical and academic engagement with its subject suggest that Dunn is reconciling his own supposedly disparate passions.

I wanted to talk with Banger Films about their passion for metal and their documentary projects because, like Dunn and McFadyen, I believe there’s always been more to the genre than Tipper Gore and the Parents Music Resource Center led us to believe. When I listen to heavy metal and hardcore music, besides genuinely enjoying the aggression, I hear popular, modern music that exhibits the virtuosity that I experienced in orchestra. In A Headbanger’s Journey, Iron Maiden lead singer Bruce Dickinson describes filling stadiums with his clear, aggressive, driving voice and being able to “shrink [a stadium] to the size of your thumb.” “My intention as a frontman,” he explains, “is to find the guy at the back of a 30,000 person stadium and go ‘you [points emphatically]—yeah, you!’” Thoughtfully considered, I realize this is fucking hard to do, but Dickinson makes it look easier then stepping on ants. Sometimes the thing that requires the most skill is the tiniest moment in a song. In Brahms ‘s 4th Symphony, the pianissimo sections are the hardest for cellos. Staying together, getting the rhythms correct even when you can barely hear your section, and not overplaying just because you’re struggling is more difficult than most complex melodies that cellos wail. As orchestras create a space for group performance, Dickinson’s musical proficiency—his art—bring people close.

A Headbanger’s Journey explicitly locates metal’s origins in 18th and 19th century classical music: Eddie Van Halen’s guitar solos are reminiscent of Bach (albeit a very drunk Bach); Bruce Dickinson’s singing is operatic; and Wagner inspires heavy bass and complex orchestration. The tri-tone, or minor fifth chord (which, according to Black Sabbath guitarist Tony Iommi, is the basis for “the evil-y sounding riffs” in songs like “Black Sabbath”) has been stigmatized and censored throughout western music’s history and is fundamental to heavy metal guitar. Metal is tapping into a lineage of musical devilishness; we innately realize this and that, along with the blood, guts, drugs and aggression in lyrics and album imagery, helps the music seem really tough. A culture of uppity boredom surrounds classical music at present, but Schumann was a syphilitic loon, Mussorgsky drank himself to death, and Tchaikovsky might have slept with his nephew. A little Satanism and bloodlust isn’t such a stretch.

A Headbanger’s Journey explicitly locates metal’s origins in 18th and 19th century classical music: Eddie Van Halen’s guitar solos are reminiscent of Bach (albeit a very drunk Bach); Bruce Dickinson’s singing is operatic; and Wagner inspires heavy bass and complex orchestration. The tri-tone, or minor fifth chord (which, according to Black Sabbath guitarist Tony Iommi, is the basis for “the evil-y sounding riffs” in songs like “Black Sabbath”) has been stigmatized and censored throughout western music’s history and is fundamental to heavy metal guitar. Metal is tapping into a lineage of musical devilishness; we innately realize this and that, along with the blood, guts, drugs and aggression in lyrics and album imagery, helps the music seem really tough. A culture of uppity boredom surrounds classical music at present, but Schumann was a syphilitic loon, Mussorgsky drank himself to death, and Tchaikovsky might have slept with his nephew. A little Satanism and bloodlust isn’t such a stretch.

In Banger Films‘ new documentary, Flight 666 (the third they’ve produced), lead singer Bruce Dickinson pilots Iron Maiden over 30,000 miles in 45 days on a world tour on five continents in the band’s 757, Ed Force One, which is emblazoned with a portrait of Eddie—grinning and waving his arm shackles. Sam Dunn, who also co-produced the film, serves as its narrator, and early on we learn that while Maiden is notoriously private, the band offered him and his crew unprecedented access. Unprecedented, maybe; revelatory, not so much. During the course of the documentary, in addition to watching Bruce command the plane in a very dapper pilot’s uniform, we see members of Iron Maiden eat pizza (Drummer, Nicko), play golf (Guitarist, Dave; Nicko, again), worship at a Mayan temple, play tennis (Guitarist, Adrian), soccer, and fish (Dave). The band members playfully cuss each other and the camera out often enough, but Metallica drummer Lars Ulrich is the only person who seems drunk on camera at any point.

When I talked with him over the phone about Flight 666, Sam Dunn told me he and co-producer Scot McFadyen had assumed that on the road with Iron Maiden for six weeks, “surely there’s going to be some sort of controversy or conflict or strife in the band.” What they found instead was a bunch of “calm and collected, low key, middle aged guys.” Standard rockumentary procedure—sit around and wait for people to yell at each other and humiliate themselves in tight pants—wasn’t going to get any results, and Dunn and McFadyen were in danger of making a movie about long-haired men who giggle entirely more than you’d expect.

Luckily, they found salvation. “Iron Maiden’s [live performances are] even better now than they were in the 80s,” Dunn told me, “which was their supposed heyday.” The focus became the truly impressive live shows and the band’s growing and devoted fan base around the world. The contrast between the off-and onstage presences of the band—the very boringness offstage and the dynamism when performing—is the only compelling tension in the film. It throws into relief the impression of misogynist, alcoholic revelry of 1980s hard rock and paints a believable picture of the discipline a heavy metal band needs to maintain if they want to be chased around stage by a 20-foot, robotic mummy for 30 years. Some Kind of Monster, the documentary on the making of the Metallica album St. Anger, also paints a believable picture, but it’s a portrait of the manipulation and misanthropy that lies just beneath the surface for so many successful entertainers. If Flight 666 is accurate, the members of Iron Maiden are much more likeable, generally aware that they’re lucky to be in a band for a living, and smart enough not to fuck it up at this point with infighting and self-abuse.

I can’t help but love the contradiction in public and private Iron Maidens. As a kid, I felt I occupied two worlds and was quietly proud of myself for that. It seemed like life would be horribly boring without contrasting but mutually dependent outlets. That never stopped being the case, although I stopped being so furious and also gave up the cello. I started treating myself and other people better, began listening to heavy metal, wore a permanent groove in a few barstools, and took to buying the biggest fireworks I could carry anytime I drove through Pennsylvania—admittedly artless methods of getting in touch with your inner juvenile delinquent. That Iron Maiden are low key in their personal lives is exciting because the unpredictable is much more interesting than consistency. Cello was cool because it wasn’t obvious. It was also hardcore because the art itself was nuanced and profound.

Heavy metal brings back feelings of rebellion and outrage, but what I’ve found, at least among the metalheads and musicians I’ve talked with, are people in search of a deeper meaning and emotional release through music. My nights at Lucky 13, Banger Films‘ chronicle of metal history, and Iron Maiden’s thrilling live performances are all surprisingly thick with emotional support and community. One of the most affecting moments in Flight 666 occurs in Colombia. It’s the first time the band has played there and before the concert, police on horseback harass the crowd as they enter. After the show ends, a couple stand, the man’s caught a drumstick and he holds it up while tears run down their faces. “I think if you grow up in the West you grow up with a certain level of being spoiled in that you have access to music on a regular basis,” Sam Dunn explained when I asked him about this image. “It’s not something that’s ever been withheld from you by the police, or the state, or religion, and I think when you go to countries like Colombia, or Costa Rica, or Brazil, you feel the energy of people who have never been able to see something like this in the flesh.” Iron Maiden, a band of boring guys, thrill and empower people by offering audiences a loud, raucous, alternative reality and a way to push back the uniformed men on horseback just a little bit. If this potential exists for those living with significantly limited freedoms, it stands to reason that spoiled girls in Brooklyn can glean a little perspective and maybe even some empowerment of their own.

In A Headbanger’s Journey, Bruce Dickinson claims heavy metal “gets into the mind of the eternal 15-year-old.” Various performers and fans echo the belief that when you stop liking heavy metal, you’re old. There’s some balance between child and adulthood that I’ve been looking for all my life—some way of undermining reality. Heavy metal and classical music concerts indulge the fantasy that I’m not just the thing I so obviously appear to be. Music this loud, this consuming, is reassuring because the virtue is explicit. There’s no uncharted space or silence in which to wonder if you’re missing the point or after the wrong things. There’s nothing but an elegantly crafted assault of noise. Standing in front of a room of drunk metalheads, swinging the mic cord before lunging to belt—Iron Man lives again!—my own eternal 15-year-old is right there with him.

**

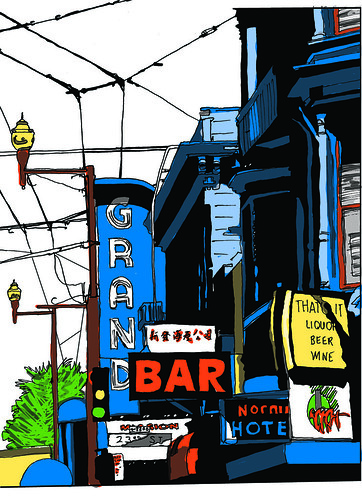

Illustrations by Laurenn McCubbin

3 responses

Great article. I’ve carried the stigma of metal-head with me for the last 25 years, and through high school and college I was constantly defending my tastes to girlfriends and social circles…as I had a fairly easy time winning friends and dates, but always never quite feeling like like I belonged with the overly-social sort. I’ve been lucky that most people I’ve grown close to could look above the Slayer t-shirt and see that not everyone who touts a horror-image laden ode to metal is a complete goddamned nitwit or a burned-out astronaut.

And I’ve made the comparison to of metal music to string movements to that intelligent and gorgeous girl who out-classed me in tastes and style, but who nodded and understood when I’d play a Chuck Schuldiner instrumental and ask her to listen to it as if it were played on acoustic strings and the distortion was that feeling you get when you know you can never express your anger, frustration, anxiety, or angst.

My wife STILL doesn’t understand, but she’s cool with it.

Up the Irons.

Nicole-

We may have been separated at birth. I’m The Rockist over at PopMatters. Metal when it is good (but especially when it’s great) is the best experience you will ever have with other humans. Hands down. I’m not into orgies, so I can’t speak for that crowd. But the only thing that even comes close is NHL playoff hockey, and that’s in another area code.

I am so excited to see High on Fire and Mastodon October 17th. I mean, I’m ready to wet myself. And if my editor can score me a press pass? You may see a nuclear cloud over the North Shore of Chicago.

Metal is identity politics at its most raw and unrefined. You want to taste my sweat? Than we’re boys. Don’t trample the girls. Codes of honor I learned at shows as a kid I can’t wait to pass on.

If you are ever in Chicago, you have a standing drink at Delilah’s, the best metal bar in town. Or just read my article about in a couple weeks (it was supposed to be this weekend-sigh!)

Nothing hotter than a girl into metal. Nothing.

Love this article, love metal but most of all I love Iron Maiden. There audio assault on your ears is highly technical and pure art. I don’t defend my love of metal I just enjoy it cause it’s all mine. I love all kinds of music not just metal but being the 15 year old kid listening to Powerslave made me realize music was more than just sex, drug and rock n roll. Metal has let me express my emotions. My fiance sent me this article never a metal fan we watched Flight 666 she never new what I felt until that documentary. Sitting across the living room she utters I think I like Iron Maiden and Bruce is kinda hot. My eyes lit up and my heart skipped a beat. She is not a devout metal head as I am, but she now has a deeper glimpse into my soul. I am 33 and I still wear my Maiden T-Shirts to work and to client meetings. I don’t look back at the 15 year old I just except that getting older doesn’t mean you give up what you loved back then you just treasure it more and I will always treasure Metal and Maiden. Thanks for writing this article I really enjoyed and thanks to my fiance for sending it to me. Now if I can only convince her to let our wedding song be “Phatom of the Opera” by Maiden. I am only partially kidding here.

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment.