There’s a story here, but it exists in illogical fragments, chaotic subtexts, and poverty economics cured in the meth-soaked algebra of need, greed and corruption. And eventually it all plays out in song. Folk songs, cowboy ballads and Narco-corridos. What you can’t see with your eyes you can feel in your heart. Hand me down my old guitar.

“Down below El Paso lies Juarez,

Mexico is different, like the travel poster says….”

-Burt Bacharach and Bob Hilliard, “Mexican Divorce”

I. Touch Of Evil

That was the summer of “birds falling out of trees,” as the Apaches might say. Looming weirdness. I’m in a beat-up Juarez taxi cab, inching slowly away from the Plaza Monumental bullring. A masked character in the truck across from us begins firing an automatic weapon over the top of the cab. Across the street at the Geronimo bar, three bodies fall into the gutter. My cab driver pulls his head down and shrieks: Cristo! Cristo! against the racket of trumpets and accordions from a narco-corrido song on the radio. Cristo, Jesu Cristo! Ayuda me! The cab lurches forward with each string of Jesus curses. I’m riding inside a pinball machine set up next to a shooting gallery. Bodies are falling outside. Bodies are falling in the drug song on the radio. My shirt sleeve is stuck on the handle of the door and I can’t seem to twist and duck my head down below the dashboard. This is not the way I want to die. I try to grab hold of the wheel but the driver pulls himself together, makes the sign of the cross, then turns down back streets and alleys that lead to the border bridge. The rat-a-tat-tat of a weapon fades into the distance. The cabbie wheels to a stop and lights a cigarette. Sangre de Cristo. Fifty pesos, por favor.

It’s another Sunday evening in Ciudad Juarez.

Back then, twelve years ago, it cost fifteen cents to enter Mexico. Fifteen cents to wheel through the turnstile and cross the river bridge into the carnal trap. The Lawless Roads. I used to think of Orson Welles’ noir classic: “Touch of Evil,” when I walked down the bridge into Ciudad Juarez. That sinister feeling which draws the gringo-rube into web of rat-ass bars and neon caves; the nerve tingling possibility of cheap drink, violence, and sex; sex steeped in sham clichés about dark-eyed senoritas and donkey shows. It’s that heady, raw – anything goes, all is permitted, death is to be scorned- routine which informed and carved out the rank borderline personalities of John Wesley Hardin, Billy the Kid, Pancho Villa, and hundreds of Mexican drug lords. Western myth now grim reality. You craved the real west, didn’t you?

The late British writer, Graham Greene, knew the border terrain. He crossed over at Laredo in 1939, noting: “The border means more than a custom’s house, a passport office, a man with a gun. Over there everything is going to be different. Life is never going to be quite the same again after your passport is stamped and you find yourself speechless among the money changers.”

Speechless among the money changers. I like that. I can’t imagine what Hunter Thompson would have come up with if he’d written a version of Fear and Loathing about the current state of affairs in Juarez. Cristo, Cristo, Cristo. Thompson once said that if you want to know where the edge is, you’ve got to go over it. Juarez is big time over the edge.

The next Sunday, following my shooting gallery ride, I decide I’ll visit Juarez again. Pushing my luck. I was in between relationships that season, and in a reckless mood. Perhaps I bought all that laughing at death routine in the lyrics of tequila drenched Charro songs. I crossed over the Santa Fe bridge and caught a bus toward the bull plaza, then wandered into the Geronimo bar, drained a Tecate, and left. I walked back toward the bridge. I was a quarter mile away when shots rang down the crowded avenue near the Geronimo. Two more bodies fell into the gutter. Cristo!

It was 1997. These were incipient skirmishes in a violent plague they now call a full-on “drug war.” The twelve year war is currently overheating; the Mexican army patrols the river with jeeps pulling canon-sized machine guns, and the body counts are higher than Baghdad. The old border town ain’t the same. The bull ring has been torn down to make a Wal-Mart; the tourist market is empty, and the Mariachi’s have all gone south. Whorehouse madams are cooking up batches of crystal meth aimed for farm kids in Kansas, Iowa and Nebraska. Everything’s gone straight to hell, since Sinatra played Juarez.

A week ago the headlines of the Spanish language paper read: Daylight shootouts, Burned Bodies, and Dead Children. Yesterday the offering was: A Thunder of 43 Corpses in the Morgue in 72 Hours. Meanwhile the English speaking paper, on the El Paso side of the river, featured a headline about someone resigning from our local school board. A little denial goes a long way here on the sunny side. It’s tradition. Graham Greene, again, in 1939: “…no day passed (in Mexico) without somebody’s being assassinated somewhere; at the end of the paper there was a page for tourists. That page never included the shootings, and the tourists, as far as I could see, never read the Spanish pages. They lived in a different world….with Life and Time…they were impervious to Mexico.”

A week ago the headlines of the Spanish language paper read: Daylight shootouts, Burned Bodies, and Dead Children. Yesterday the offering was: A Thunder of 43 Corpses in the Morgue in 72 Hours. Meanwhile the English speaking paper, on the El Paso side of the river, featured a headline about someone resigning from our local school board. A little denial goes a long way here on the sunny side. It’s tradition. Graham Greene, again, in 1939: “…no day passed (in Mexico) without somebody’s being assassinated somewhere; at the end of the paper there was a page for tourists. That page never included the shootings, and the tourists, as far as I could see, never read the Spanish pages. They lived in a different world….with Life and Time…they were impervious to Mexico.”

In El Paso, the refutation melts into absurdity. This morning’s El Paso paper announced that the “John Wesley Hardin Secret Society” would meet at 6 pm in the Concordia cemetery. There would be “old west re-enactors and six gun shootouts” commemorating the night Hardin met his demise on the streets of old El Paso. Hardin was an outlaw who claimed he’d killed 42 people before he went to prison in 1878. When he was released, brandishing a law degree, Hardin moved to El Paso and went back to his old ways. One night Sheriff John Selman shot him in the back of the head, then drug the body out into the El Paso street so the locals could gawk at another dead lawyer with a big mouth.

Five years ago the City Council was entertaining the idea of a giant Old West theme park in downtown El Paso. Something to lure the tourists from Germany and Japan. Shooting re-enactments and dance hall girls; three shows a day. But what the hell we need that for? We have Juarez a quarter mile away and it costs a few pennies to cross over. Or tourists could set up chairs on top the Holiday Inn Express and bring their binoculars.

This morning, after the John Wesley Hardin story, I turned that page in section B where there was a short item about two El Pasoans slain yesterday in a Juarez bar shooting. Back page stuff. Hidden near the end of the story was the astounding body count: nearly 2900 people, including more than 160 this month alone, have been killed in Juarez since a war between drug traffickers erupted January 2008. John Wesley Hardin wouldn’t stand a chance.

2900 bodies in 20 months. Welcome to the frontier, where “God and the Devil wheel like vultures, and a loose fences separates the good man from the bad.” (Nicholas Shakespeare on Graham Greene.) We are walking the streets between doubt and clarity; savage reality and indifference. Shooting re-enactments and World War Three. This is El Paso-Juarez, an extreme western edge of Texas that no Texan east of Sierra Blanca would lay claim to. The wild, non-fictional Mexican West. Hollywood and a million dime novels never quite got it right. Sam Peckinpah wasn’t even close. El Paso-Juarez is the American frontier in every sense: the land or territory which forms the furthest extent of a country’s settled or inhabited regions. The outer limit. (Webster’s Unabridged.)

And now, September 4, 2009, as I was trying to put this essay to rest, the biggest shoot-out in the history of Juarez took place in a Juarez drug clinic. 17 people slaughtered. The carnage hit the front page of the New York Times and, even weirder, the front page of the El Paso Times: Juarez in Shock: Attack Considered City’s Worst Multiple Shooting. The New York Times coverage sounded as if it were lifted from a James Elroy novel: a thick layer of blood covered the concrete floor…a chained dog had been shot…the smell of death hung in the air.” God and the Devil, wheeling like vultures.

And now, September 4, 2009, as I was trying to put this essay to rest, the biggest shoot-out in the history of Juarez took place in a Juarez drug clinic. 17 people slaughtered. The carnage hit the front page of the New York Times and, even weirder, the front page of the El Paso Times: Juarez in Shock: Attack Considered City’s Worst Multiple Shooting. The New York Times coverage sounded as if it were lifted from a James Elroy novel: a thick layer of blood covered the concrete floor…a chained dog had been shot…the smell of death hung in the air.” God and the Devil, wheeling like vultures.

And finally, it’s September 11, 2009, and while the world is remembering 9/11 and the twin towers going down, there’s a little item on page 9A of the El Paso Times: “It is not uncommon for U.S. citizens to be part of Mexican drug cartels because cartels have placed cells in more than 200 cities across the United States. According to the Department of Justice, Mexican cartels…pose the greatest organized-crime threat to the United States and it’s people.”

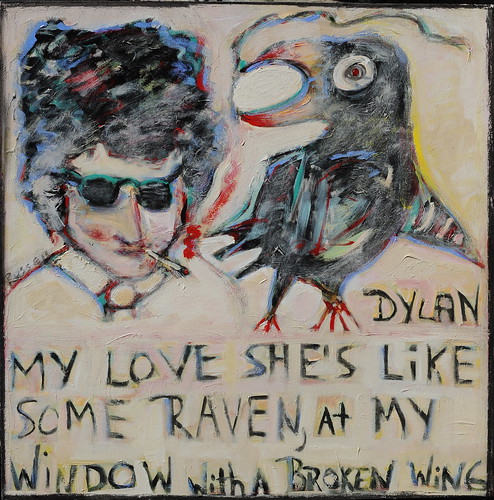

Incomprehensible? You have to understand the full contextual layout: cultural, geographic, historic. Then dim the lights and listen to the music: either Dylan’s “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues,” or Marty Robbin’s “El Paso,” or one of a thousand narco-corrido songs where the bad guy is the good guy, and behind every lyrical gravestone is buried a lost verse to “The Streets of Laredo.” This is gunfighter country.

II. The Place of Dead Roads / Mean as Hell

“The fact is, Old Boy, the land is so poor

I don’t think you could use it as a hell anymore

But to sweeten the deal and get it off my hands

I’ll water this place with the Rio Grande….”

-God Talking to the Devil, Johnny Cash, “Mean as Hell”

When Horace Greely said “Go West Young Man,” he could not have been aiming the kid in the direction of El Paso-Juarez. Naw. Not unless he had a twisted sense of humor, or the young man he was chatting with was Billy the Kid, who was born in the Bronx. But off I went. In 1997 I moved from Brooklyn to El Paso, traveling 2800 miles in a U-Haul Truck. 1400 hundred miles, half the journey, was across the width of Texas. From the blues-drenched East Texas thickets and on through the boggy midlands and rusty oil derricks of the dying swap meet towns. On out toward the Chihuahuan desert. You don’t know Texas unless you driven the width. Four hundred miles west of Austin the air begins to dry out, the birds of prey grow larger, and the land flattens out into a reddish-orange sand punctuated with dwarf Mesquites and Palo Verdes. The surface of the earth looks like Mexican flan that’s been left in the oven too long. You’ve got a few hundred miles to go. Carry water.

As you hit the city limits, if it’s night, you’ll see a carpet of the ten million blinking lights over in Ciudad Juarez. El Paso is the sleepy 1950s old west town laid out on the front of that carpet. To the left is the vintage Plaza Hotel – one of the first Hiltons; on the top floor is the penthouse where Liz Taylor lived with Nicky Hilton. The Plaza’s been closed for years. Hell, the town has been semi-dead for pretty much half a century. If you turn off towards downtown you’ll hit the central plaza with its fountain and the fiberglass sculptures of leaping alligators. Up until the 1960s there were real gators in there, but too many drunks fell in and lost essential limbs. Local color abounds.

Most people don’t exit Interstate 10. They sail through this sleepy downtown and avert their eyes from the poverty shacks of Juarez; keep right on going towards Tucson or Los Angeles. The Promised Land lies elsewhere. Interstate 10 finally dead-ends into the Santa Monica pier, near the antique merry-go-round where you can whirl your kids around in the Pacific sea air, knowing you made it through hell and the badlands.

Occasionally a tourist from Frankfurt or Des Moines will make the unwise decision of turning off; driving the kids over the bridge into Juarez in search of “a real taco.” That might be a very bad mistake, senor. The rules are different on the other side.

Johnny Cash once recorded a recitation titled “Mean As Hell,” in which The Devil is looking for a hell on earth, and God gives him a plot near the Rio Grande which sounds like El Paso. That might have been after Cash was busted here for smuggling ten thousand pills over from Juarez. Ah, the history! Wasn’t it Raymond Chandler who quipped: “No one cared if I died or moved to El Paso?” That quote was ringing in my ears as I stopped here and unloaded the truck. I was home. It was a long long way from Brooklyn. 1400 miles and half a century. In El Paso there was no music scene, no resort hotels, and no welcome wagon. Suited me. So many critics had called me an “outsider” I finally decided to go find where the American outside really was.

I bought a 1930s historic adobe on three acres and settled down to hide and write songs and novels. I was surrounded by rock walls, barbed wire and cactus. Cormac McCarthy lived in a rattle trap adobe up on the mountain; trying to do the same thing. To be left alone to write. Unfortunately fame and fans hunted Cormac down and chased him away to Santa Fe. I’m still here. St. Thomas of the Desert in this dry wasteland where extremes meet. Where men balance their own aridity and desire for reclusiveness with that of the landscape. Like the desert fathers in Egypt, I came here not to find my identity so much as to lose it, eradicate an old personality and re-invent a new one. Society is a cave; the way out is solitude. But there’s a deep history here which begins to claw at you. The history seeps into your spirit and begins to inform the writing with that odd and tangled chaotic soul of the borderlands.

I bought a 1930s historic adobe on three acres and settled down to hide and write songs and novels. I was surrounded by rock walls, barbed wire and cactus. Cormac McCarthy lived in a rattle trap adobe up on the mountain; trying to do the same thing. To be left alone to write. Unfortunately fame and fans hunted Cormac down and chased him away to Santa Fe. I’m still here. St. Thomas of the Desert in this dry wasteland where extremes meet. Where men balance their own aridity and desire for reclusiveness with that of the landscape. Like the desert fathers in Egypt, I came here not to find my identity so much as to lose it, eradicate an old personality and re-invent a new one. Society is a cave; the way out is solitude. But there’s a deep history here which begins to claw at you. The history seeps into your spirit and begins to inform the writing with that odd and tangled chaotic soul of the borderlands.

Five hundred years ago a Spaniard, Don Juan de Onate, rode his tall Andalusian horse across the river and claimed this land for Spain. The boys sat down and rested on the river bank and roasted up a few javelinas. It was the first Thanksgiving in America, years ahead of that Plymouth Rock routine. A few hundred years later Pancho Villa rode up and down this same river terrorizing the citizenry; changing his political allegiances as often as he changed his favorite ice cream flavors; marrying dozens of women at a time for the cause of the Revolution. Villa inspired a thousand folk songs and corridos; countless books and movies. His mythical shadow is long. Ask any soldier in a drug cartel.

Later Villa attacked Columbus New Mexico and the U.S. sent Black Jack Pershing, with young George Patton in tow, but they never caught him. There’s not much about that in our grammar school history books. America had been attacked and invaded and we couldn’t catch the rotten bandito, even though he was only a few hundred miles away. Sound familiar? We could not follow the signs or the spoors; and the blood spoors on this desert can be traced back hundreds of years, beyond Mexico and Christian Spain, to the Moors. Those bastards, the Moors! They sat a horse pretty damn good. They were the forefathers of the modern American cowboy and they rode their little Arab ponies hell-bent on bloodlust. And you couldn’t catch ’em.

During the Mexican revolution the people along the American side of the Rio Grande would take chairs up on their roofs and watch the war on the other side through field glasses. The late El Paso painter, Tom Lea, shared that anecdote with me. He died a few years ago; he taught me many things about this “wonderful country,” including the fact that Pancho Villa had put a price on young Tom’s head when he was six years old. Tom’s father was the Sheriff of El Paso and kicked Villa back across the river a few times. Get the hell out of here you saddle-faced son of a bitch. Little Tom had to have a bodyguard to go to school. Things ain’t changed a hell of a lot. There’s an outlaw feel in each little cloud hanging over my potted agaves.

I crossed the Santa Fe bridge many times in 1997 and heard the rat-a-tat-tat which foreshadowed the rumor of a coming war. After those initial skirmishes came a plague of murdered women. A modern horror story. Hundreds of female bodies dug up in the desert surrounding Juarez. Serial murders? Drug war casualties? Maquiladora workers who walked home late at night? The rash of killings has never been fully explained. Hillary Clinton, in addressing human rights violations and rape in the African Congo, talked about women being the first victims on the front lines of wars against humanity. Holds true in Juarez. A few years ago Hollywood and dozens of journalists came; books were written. Movies were released. Hollywood went home. Committed actresses turned their attentions to other “third world” causes. Or began adopting babies in Somalia. In Juarez matters got worse. A huge black cross went up on the Juarez side of the bridge with hundreds of railroad spikes hammered into it. One for every murdered woman. The sign at the top said: “ni una mas.” Not one more.

But the carnage spread out, disregarding gender and age. The full war was on. The media forgot about the dead women. The headlines, if there were any, were about the “war against drugs,” listing facts baked in the tired rhetoric of presidents and army generals. This time the victims were women, men and babies. You can’t be too precise with an automatic weapon. Not if your wired to the gills on crack and sotol. Not if you’re firing in a crowded bar or bus station. So the Mexican president called in the army.

III. It Isn’t Going Away and Nobody is Going to Destroy It

When I walked out into my cactus garden this morning, I heard that familiar old rat-a-tat-tat of automatic gunfire drifting through the Cottonwood trees to the south. Or was that a cadre of nail guns from the mushrooming housing developments which have ruined the last of our upper Rio Grande farming Valley? You never know. The cartels would be stupid to carry the war over to this side, but the corruption on both sides of the river is pervasive and deep. It effects most of the almost three million people who try to live in this valley the Spaniards called El Paseo del Norte.

El Paso is an abandoned midway of cultural impoverishment. I’ve always wondered why we didn’t have the amenities of San Antonio or, say, Tucson or Phoenix. There are no resorts, tourist attractions, or Whole Foods stores, and even precious few decent restaurants with an outdoor patio. Years ago the city planners could have diverted part of the river into downtown and capitalized on the scenery, in the tradition of as San Antonio. El Paso might have rivaled Tucson as a desert destination; a retirement haven. The climate is a little more temperate than Tucson or Phoenix. But when corporations and big business came calling, decades ago, the city council and powers-that-be delivered the ultimatum, which went something like: We’ll allow you to move in here, but what are you going to do for us? Big Money squirmed with distaste and waltzed away.

El Paso is an abandoned midway of cultural impoverishment. I’ve always wondered why we didn’t have the amenities of San Antonio or, say, Tucson or Phoenix. There are no resorts, tourist attractions, or Whole Foods stores, and even precious few decent restaurants with an outdoor patio. Years ago the city planners could have diverted part of the river into downtown and capitalized on the scenery, in the tradition of as San Antonio. El Paso might have rivaled Tucson as a desert destination; a retirement haven. The climate is a little more temperate than Tucson or Phoenix. But when corporations and big business came calling, decades ago, the city council and powers-that-be delivered the ultimatum, which went something like: We’ll allow you to move in here, but what are you going to do for us? Big Money squirmed with distaste and waltzed away.

Downtown El Paso looks much the same as 1955, except the historic storefronts are now bargain Korean “fashion” joints, Mexican CD outlets, and pawn shops. Oh, there’s a new art museum, the Camino Real hotel, and a renovated theater; but the rest of downtown seems an extension or Juarez. Instead of revitalizing the downtown, the city council allowed a handful of housing developers to go out and destroy the upper and lower irrigated farming valleys along the Rio Grande. Thousands of acres of prime agricultural land were traded off for a quick shot, hangdog economy based around cheap houses which will collapse in thirty years; long before a few hundred thousand Mexican families have paid off their long-term mortgages. And there you have it. The seven capital sins dance like harpies along this river bank: Pride, covetousness, lust, anger…and the Queen Bee Mother, corruption. What are you going to do for us? Cristo!

But you’re interest in the body count, no? The drug war. And the bottom line or the big Why of it all? Amigo, the real story will not be delivered by presidents, politicians, army generals, police sergeants, newscasters, DEA agents, sociologists, dead-line journalists, and all those whose livelihoods dance around the twisting of that murky little gap between doubt and clarity. Fact and furor. Pride and paranoia. The slant and the spin. In the kingdoms of the blind and corrupt, the one-eyed billionaire drug lord is King. Always and forever.

Tucson author Charles Bowden is able to give you the lowdown; he may be our most capable and truthful witness. Bowden surmises that it’s “nonsense” that the United States and Mexican governments are partners in a war against drugs. He calls it a war for drugs as the Mexican economy collapses. Here’s Bowden on the employment of the Mexican Army:

“They’ve moved into Ciudad Juarez and the murder rate has

exploded there. There’s 8000 to 10,000 federal troops and

Federal police now in Juarez. In 2007, there were 300 murders,

A record for the city. But is 2008, there were 1600 people

slaughtered. This year there’s been over 1200 people slaughtered.

That’s the achievement of the Mexican army. Every place they go

They’ve terrified people…the soldiers run amok.”

(democracynow.org 8/11/09)

Bowden asserts that Mexico would sink without drug money because the oil fields are collapsing down there, and Mexico earns up to $50 billion a year in foreign currency from selling drugs. Bowden’s summation: “Drugs have penetrated the whole culture, and it isn’t going away. And nobody is going to destroy it.”

And the guns over there? Most of them come from the United States. It’s estimated that over two thousand a day cross the border into Mexico. There’s only one gun store in Mexico, in Mexico City, and you have to be a cop or a government official or an army person to get in there. The drugs come back across the other way. Marijuana, cocaine, heroin, and the newest and most deadly front runner: crystal meth. As the United States cleans up our own meth labs and regulates pseudo ephedrine in cold tablets (needed to make meth), Mexican cartels have risen to the occasion; a more purer form is now being manufactured over there. Most of it comes back across this river.

And what do we do with these gruesome facts? Hell, we juggle them up and down and pretend we’re appalled; slide them across the news monitors; then jam them into folders, reports and journals no one reads. This is old territory for me. My master’s degree was in criminology. Then I became a songwriter, and  part of that transition was sparked by the frustration was dealing with a Social Science which operates on the wasteful billion dollar dole of research grants, and then publishes findings and statistics in a sterile academic vacuum. Journals hidden in dusty library stacks. I told my old Criminology mentor, back in 1969, that the world would be better off if he published his findings in Playboy, or the New Yorker, or even The Reader’s Digest, rather than these dry and sterile journals which preached to the academic choir. Then I picked up my guitar and waltzed away. Bob Dylan was more of an agent for social change than C. Wright Mills.

part of that transition was sparked by the frustration was dealing with a Social Science which operates on the wasteful billion dollar dole of research grants, and then publishes findings and statistics in a sterile academic vacuum. Journals hidden in dusty library stacks. I told my old Criminology mentor, back in 1969, that the world would be better off if he published his findings in Playboy, or the New Yorker, or even The Reader’s Digest, rather than these dry and sterile journals which preached to the academic choir. Then I picked up my guitar and waltzed away. Bob Dylan was more of an agent for social change than C. Wright Mills.

So what’s the good news, Tom? Why the hell would anyone stay in El Paso?

IV. Last Stand in Patagonia

“Everything in nature is lyrical in

it’s ideal essence; tragic in it’s fate,

and comic in its existence.”

-George Santayana

El Paso is my own Patagonia. Outside and over the edge. Lyrical in it’s essence, tragic in its fate; comic in its existence. But, it’s a peaceful place. You find that amusing? The war has not spilled across the Rio Bravo. Life is simple and cheap. I like the people. There are ten thousand Mexican restaurants, and the sun going down on the Franklin Mountains always elicits my daily prayer of gratitude. Life seems more precious on the last, wild frontier. There is a raw beauty and a lack of pretense. And that wonderful history which has seeped into my blood; emptying into song and story.

I irrigate my fruit trees from the Rio Grande and think of the days when Sinatra and Nat King Cole and the Kingston Trio played down river in Juarez. The days of the “quickie divorce” Burt Bacharach wrote about. Marilyn Monroe divorced Arthur Miller in Juarez, then strolled down to the Kentucky Club and bought the house a round of Margaritas. Hell, the Margarita was invented in Juarez in the late 1940s. Gypsy Rose Lee stripped at The Palace Club and Manolete fought in the bull ring. Steve McQueen died over there in a clinic. This is a place to write and to absorb the history. A place to be left alone to create and conjure up your own meaning to events on either side of the river. Forget about the final answers. They will not be forthcoming.

Our gun laws are not going to change. Certain drugs will not be legalized. The drug cartels will never disappear. These are people supporting what’s left of the Mexican economy. Some drug czars are revered in narco-songs and others might throw monetary support the local village schools and hospitals. The “war” will either be fought to a conclusion or go underground, like a hidden desert river which appears hundreds of miles away. Always running with human blood. Cristo. Jesus Cristo.

I’ll watch it all go down from Ardovino’s Desert Crossing, the great bar and restaurant which sits up near Mt. Cristo Rey, overlooking the lights of El Paso. (Okay, there are a few good bars here.)Trains roll cross the mountain at happy hour and border patrol trucks chase illegals through these desperate, yucca-choked rocks and rills. Over yonder the ugly black border wall snakes across the sandy hills. The wall is our knee-jerk attempt to intimidate Mexican illegals who want to do the dirty work we shun. But this is still the old west, amigo. Those class equations have always been such. The Chinese built the railroads with a shotgun at their head, and their opium was always available in the back of the chop suey joints and whore houses. The “greasers” and “chinks” did the dirty work; and those red devil Apaches raided our horse camps until we sent Geronimo down to Florida to chill out. We’re getting it under control, ain’t we? It’s the coked-up, Manifest Destiny politics of Methland.

These are the far regions and outer limits of America. La Frontera. We’ve twisted and exploited and mined the old West for those clichéd, watered-down versions of violent cowboy and Indian stories, where John Wayne kicks ass and rides away in a white hat. Now it’s the drug soldiers and assassins in baseball caps who hold court with submachine guns, which we sold ’em. They’re the ones kicking ass. You can write it from any political angle and subtext. You can walk around leaning on the moral, self righteous crutch of whatever religion and political party or news magazines you subscribe to. The palaver don’t cut much on the backstreets of Juarez. There’s a story here, but it exists in illogical fragments, chaotic subtexts, and poverty economics cured in the meth-soaked algebra of need, greed and corruption. And eventually it all plays out in song. Folk songs, cowboy ballads and Narco-corridos. What you can’t see with your eyes you can feel in your heart. Hand me down my old guitar.

But hell, it’s sundown. I’m parched. The mountains are turning crimson and the beer is cold. The rat-a-tat-tat might be gunfire, or the ice in the blender over there in the Mecca bar. I’ll leave you to your safe and well-edited taste of doom flashing across the six o’clock news. Somebody inside the bar has played Dylan’s “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues,”and for a brief moment I have all the poetic details I need about the frontier and these borderlands I’ve come to love. But no answers, amigo. Never any real answers. Only a noir lyricism which drifts out between the comic and the tragic.

“When you’re lost in the rain in Juarez

“When you’re lost in the rain in Juarez

And it’s Easter time too

And your gravity fails and negativity

Don’t pull you through

Don’t put on any airs

when you’re down on Rue Morgue avenue….”

-Bob Dylan

Tom Russell

El Paso-Juarez

September 11, 2009

Art by Tom Russell

18 responses

Curse of the fuku like in Santo Domingo. I don’t know if crossing my fingers and saying zafa would even help. Here, I’m reminded of The Brief and Wonderous Life of Oscar Wao. El Paso doesn’t sound like a place that’s superstitious. All the carnage carries over from the path of wicked dictators. Makes you sort of wonder if all these socioeconomic manipulations of human consciousness aren’t ancient wars from days of the Incans and Mayans. Thanks for sharing these experiences and descriptions.

thank you …this says ao much about the human psyche.i don’t, however, agree with Jesse’s comment that el paso is not superstitious;were it not, it would be a ghost town. love the artwork (as an artist..mostly abstract, but formally trained, i always look for the good stuff !! thank you, jude

Wonderful essay Tom… You inspired me to ask the question, “where and when will this madness stop?†Prohibition was a time when Al Capone and his Gangs ruled the streets of America and was a friend to the cop on the beat as well as the porter who shined his shoes in sleeping cars that ran between New York and Chicago. What stopped Capone and many who emulated his way of life was “the end of prohibition”. Mexico has recently taken a first step in legalizing small amounts of heroin, cocaine and pot. Even America finds marijuana shops open to anyone with a “medical need” even if that need is brought on by the stress of a long day at work.

We of the majority hope to see an end to the “drug war” mentality where killing is justified by both sides. Could the answer to putting the drug lords out of business be the “commercialization of drugs?” Once the buying and selling of small amounts of drugs becomes legal, can the day when Panama Red replaces the Marlboro Man be far away? Left to it’s ways, Wall Street will sell drugs to mainstream America the same way it did alcohol once prohibition ended in 1933.

When drugs are legalized, legitimate businessmen will replace the drug lords in the same way that Budweiser and Bush Gardens replaced Al Capone and his Gang. Say it can’t happen? Look at the dozens of bills in various State, County and City governmental offices seeking to tax an ounce of marijuana he same way beer and wine is justified and taxed; to keep real estate taxes down or to help pay for our children’s schools. This is the same marijuana that use to be sold by your local back street dealer now respected main street businessmen. The States of California, Rhode Island, Michigan, Washington, Maine, Maryland, Vermont, Oregon Nevada, New Mexico and Massachusetts want a part of this action. Even bastions of liberality such as Mississippi, North Carolina and New York have recently decriminalized possession and use of the once considered “evil weed”.

Could the taxation of drugs be the weapon that finally ends America’s Drug War and puts the drug lords out of business? Since Alaska legalized small amounts of marijuana in ones home in 1975 (see: Ravin v State of Alaska 537 P.2d 494 (Alaska 1975), drug lords see no need to do business in Alaska. Alaskans have learned to grow pot better than drug lords do and do not bring the added baggage of shoot-outs, street gangs or corrupted politicians that follow most drug lord sponsored activities… Whether this Alaskan model will be followed by enough States to put the drug lords out of business will be anyone’s guess. Yet, it may offer the best chance at ending this on going drug warfare that has permeated the streets of America and Mexico and especially the border towns of El Paso and Juarez and since Nixon was elected and started this madness in 1968.

Perhaps someday soon, the rat-a-tat, tat of gunfire heard in the streets of El Paso will be replaced by the sound of change-ching as money is being spent by tourists coming back to the border towns no longer afraid of being caught in the cross-fire of drug cartels and drug warriors hell bent on claiming that God is on their sides. Peace, Joe Ray Skrha, Attorney at Law, from Kenai, Alaska

Mr Russell, a long time fan of your work and now a convert to your blog writings. Utterly fabulous stuff. Greetings from Australia. Jason

Tom,

Man, this is great! The perfect place and with your art, it speaks a million words. I look forward to more, in whatever form you choose to do it in.

With much appreciation.

John

Thank you Mr. Russell

I am also a long time fan of your music. Your written words are just as striking and your paintings exquisite. I enjoy reading your blog and would love to see you as a regular contributor to the rumpus…

I used to visit El Paso in the 60s and 70s. My cousins did all their shopping in Juarez. I have very good memories of both cities. You hit the nail on the head. Mexico is a failed nation and the only things keeping it from a total meltdown are monies sent from Mexicans working in the U.S., oil, and narcotics.

If our desire for cheap labor wasn’t so great, our thirst for drugs less, and our border not so porous, Mexico would have had another revolution as its best citizens have fled to work and live here.

The corruption permeates every part of society so you are right about it not going away. I’m in favor of legalizing marijuana, but that’s just one product line they are peddling. What do you do about meth, heroin, and cocaine?

Great article, reminding me of my time at Easter time of 2006 when I followed the Dylantour across New Mexico, into El Paso and the rest of Texas, where I took that walk across that Rio Grande river (which didnt look very Grande to me at all by the looks of it from that bridge) into Juarez feeling indeed very unsafe the rest of my afternoon as a obviously sticking out like a sore Tom Thumb blond too rich in their Mexican eyes Dutchman before heading back to watch Bob sing those very lines you mentioned…great concert…dreary place…but very interesting to see those two conflicting cultures in those bordertown cities across the borderline….if you reach that broken promised land…and all those dreams slide through your hands…and it’s too late to change your mind…when you’ve paid the prize to come so far, just to wind up where you are,…and you’re still just across the borderline…anyway…up and down the Rio Grande, a thousand pootprints in the sand reveal the secrets known and divine…a lot of lyrics went through my mind driving around that part of the world where the Brownsville Girl is not far and Henry Porter used to live…what I did wonder about for quite some time is the title of that movie that you’re refering to about those Juarez women being killed and buried in that very same sand where those thousand footprints can be found….I saw the movie….but forgot it’s title…another movie working like a corkscrew in my heart….anybody? Thanks, Hans.

insightfully cleaver about a place that can kill you for just passing through, let alone living there. One of the Golden Gates to the American Dream with a dirty door mat.

I’m in the process of doing a blog based on a 3 year journey through Latin America and to see and read your blog is an inspiration and humbling at the same time.

Muchas Gracias

What bullshit! I’m all in favor of literary license, but the “shooting gallery ride” has been a staple of U.S. fiction about Mexico for as long as I can remember… most of it passed off as truth. Juarez does have a high murder rate, and there has been, for the last couple of years, shootouts now and again between gangsters and police (or, lately, military units), and– most importantly — it is a frontier town (to our way of thinking, the frontier between civilization and the wild north) — but street violence of the type described by Russell is so very rare that it is NATIONAL news. As it is, Russell uses a collection of national headlines (including one about a day care fire in Hermosillo) from a country of 120,000,000 people as if all the random violence is within his purview.

“Speechless among the money changers”. A lovely phrase, but since everyone changes their money at the ATM machines, or in a bank, or uses a casa de cambio, I assume this is a metaphor, not meant to even approximate reality.

Thank you, Mr. Russell, that was uncanny and striking, like a tuneful howl. I loved it. I live part of each year in Mexico–but not Juarez, I’m too afraid to go there. I’m in the Bay Area now just waiting to get my swine flu shot before I go back. I fly right over the Frontera to the central Sierra Nevada states for safety. My Mexican work visa lists my occupation as “journalist,” which is like having a target drawn on your back for the drug lords, even though I won’t write about drugs down there. The kidnappings in Mexico City have extended to the middle class, people without wealth, but, hey, they’ve got family who care so maybe a little dinero too. There are so many beautiful people in Mexico praying every day for the evil to end.

Please keep writing on this subject because even the crystal meth machine could soon change, and then what will the violent ones do for money? I just read there is a new “shake and run” production method catching on in the US: fewer ingredients dumped in a liter-sized, plastic soda bottle, and then some chump runs down the street to mix it. You don’t need a big lab or organization to pull this off.

I’ll be back in Mexico in time for Dios de Los Muertos to contribute to a public altar for the women killed in Cuidad Juarez.

It’s definitely a rough, wild place and has been for years. But my gringo grandmother was born south of Juarez and lived there with her gringo family until Pancho Villa’s men chased them out. You’d be surprised to know that a lot of the gringos went back. They’ve never much liked the “liberal” United States.

My great-grandfather on a different line moved with his family to Sonora to make a new settlement in the 1890’s only to see it wiped out by the Indians. His family then moved to Chihuahua where he met his future wife. His family included an “aunt” and her kids. She was really his father’s polygamous wife.

When he got married, he went to work with a crew building a railroad through Sonora and used the money to build a furniture store. The store had an adjoining wall to the Federales fort and when he went back, after he fled with his family to El Paso to escape Pancho Villa, he found that the furniture had been burned and the wall breached by the revolutionaries to attack the soldiers in the fort.

Sometime in this time period, a posse was formed to chase Pancho Villa who successfully hid out in the badlands in western New Mexico and eastern Arizona. He said it was the land of a thousand caves and Pancho Villa could have easily hid in any one of them.

He briefly had a dairy farm near El Paso on the New Mexico border. My grandfather was born on the Texas side though he would never admit it. He was always a New Mexican through and through.

Just a summary of the stories my great-grandfather used to tell me.

Please send me an email somebody on vandefruits@yahoo.com with the name of this movie about Juarez that came out about three years ago about those women getting buried in the sand, I forgot its name and would love to see it again…Many thanks in advance, Hans.

As a Canadian who has passed through El Paso and Ciudad Juarez a few times — once, notably, on the day that Marty Robbins died — I had particular reason to be interested in your fine article. But what really knocked me out was your art work. It is brilliant. Thanks for sharing both.

Richard Grabman: Greene was writing of a trip to Mexico in the late 1930s. You know, BEFORE ATMs…

Richard’s right — this stuff about constant machine-gun fire in the streets is hyperbolic bullshit. It also seems pretty strange to write a piece that talks about so many white male tourists and transplants who’ve made hay of the border — Graham Greene, Cormac McCarthy, Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, the guy who wrote this — without mentioning a single non-white writer. (Not even Bolano, whose 2666, the biggest book of last year, was about the murders of women in Juarez.)

Peckinpah’s movies weren’t about the border though, it was a nice place for him to set his brutal dramas, but his movies were never about the border. In my mind he is the greatest American director who ever lived. Ford, Hawks and Wells don’t even compare. “Touch of Evil” is a good one, I agree. Film school types won’t agree with me, but I do’t care.

Peckinpah talked about men, their relationships, death, love and redemption, and he loved Mexico as much as anybody. He lived for that stuff. I’ve never been there myself, but I know that it ment alot to old Sam. Writing his movies off as hollywood BS is unfair. His movies were indeed butchered by the studios, and he had a hard time with the god damn producers, but at least he got them made. And “The Wild Bunch” would never fly today. I’ve seen that movie so many times, to me it’s the greatest movie ever made. “We all dream of being a child again, even the worst of us. Perhaps the worst most of all”. That’s poetry. I think alot of Peckinpah’s movies are masterpieces, “Pat Garrett”, “The Wild Bunch”, “Cable Houge”, “Bring Me The Head of Alfredo Garcia” and “Junior Bonner” are all masterpieces and I’ll go to my grave saying that. I don’t know if he got the border right in all of them, but he got something right for sure.

Nice to see that you are a Hunter Thompson fan. I’ve been reading his stuff for years. He was a wild, untamed spirit. I miss him like hell.

Those commentors like Richard Grabman who would criticize Tom’s charicterization of the exterme level of violence in Jaurez are ignoring the facts, the statistics and the names and faces of the dead. They would claim things are not so bad but they are just being defensive with their national pride seemingly at stake to them. But shame is due and Mexico has always been corrupt and the poor stay poor. Things are no better in 2010 than when Tom wrote this – the killings are still an every day occurance. Until Mexicans choose to make huge changes like to pay salaries which are enough for police and judges not to need bribes then nothing will change. The wealthy elite have been satisfied by outlawing guns and hiring their own private (armed)security and living in compounds – but someday perhaps that will lead to another revolution.

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment.