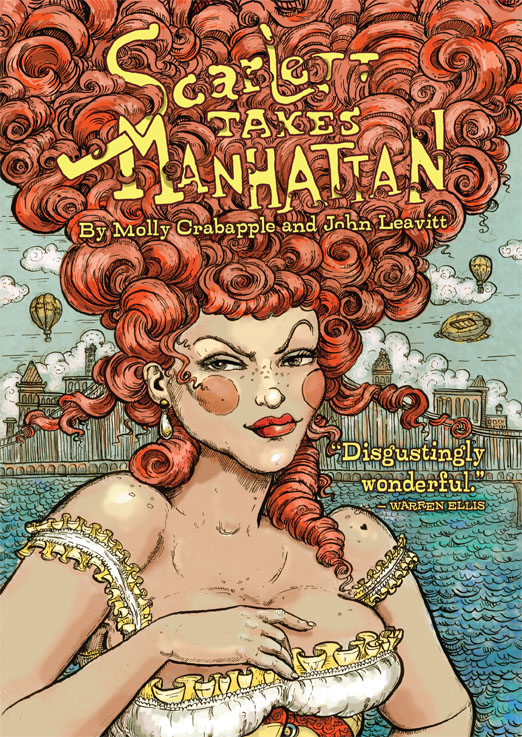

Molly Crabapple is an artist, model, entrepreneur, and one-woman pen-and-ink revolution. She’s probably best known as the founder of the worldwide burlesque life drawing phenomenon, Dr. Sketchy’s Anti-Art School, which has opened branches in 80 cities since it launched in Brooklyn four years ago. In addition to injecting some much-needed life into life drawing—and when I say life, I’m talking specifically about booze and beautiful women—she’s also a very accomplished illustrator. Her fantastically detailed Victorian images have appeared on gallery walls, magazine pages, posters and album covers around the world. Most recently, Molly collaborated with writer John Leavitt on her graphic novel debut, Scarlett Takes Manhattan, out now from Fugu Press.

Molly Crabapple is an artist, model, entrepreneur, and one-woman pen-and-ink revolution. She’s probably best known as the founder of the worldwide burlesque life drawing phenomenon, Dr. Sketchy’s Anti-Art School, which has opened branches in 80 cities since it launched in Brooklyn four years ago. In addition to injecting some much-needed life into life drawing—and when I say life, I’m talking specifically about booze and beautiful women—she’s also a very accomplished illustrator. Her fantastically detailed Victorian images have appeared on gallery walls, magazine pages, posters and album covers around the world. Most recently, Molly collaborated with writer John Leavitt on her graphic novel debut, Scarlett Takes Manhattan, out now from Fugu Press.

Scarlett is the story of a girl who rises to prominence in the burlesque scene of 1880s New York through a potent combination of sexuality and ambition. Like many of the women in Molly’s illustrations, Scarlett mixes elaborate, painted-on stage beauty with self-awareness and a sarcastic streak. As it turns out, that’s an ideal recipe for success in business—especially when your business includes fire-eating, fucking and politics. While the story is fun, sometimes funny, and yes, very sexy, it’s also a sharp commentary on class and gender in the era of the great political machines. In our current recessionary moment, there’s nothing quite as refreshing as an escape to a more decadent time, but Molly doesn’t let the reader off without the sense that old New York had its own set of problems.

The Rumpus: Where did the idea to do Scarlett start?

Molly Crabapple: Scarlett’s a prequel to Backstage, a webcomic Leavitt and me did on Act-i-vate for most of 2008. Backstage is the story of two reporters who have to find out if the death of reigning fire queen Scarlett O’Herring was an accident, or murder. Now, all biographies end badly—Scarlett’s especially. The Scarlett of Backstage is a faded grand dame, a 1904 Norma Desmond with a morphine habit and a sailor’s mouth. We wanted to show her when she was young and bright and ambitious. Scarlett Takes Manhattan tells that story. It’s light and sexy. But, for a reader who is familiar with my work, it has a dark edge.

Molly Crabapple: Scarlett’s a prequel to Backstage, a webcomic Leavitt and me did on Act-i-vate for most of 2008. Backstage is the story of two reporters who have to find out if the death of reigning fire queen Scarlett O’Herring was an accident, or murder. Now, all biographies end badly—Scarlett’s especially. The Scarlett of Backstage is a faded grand dame, a 1904 Norma Desmond with a morphine habit and a sailor’s mouth. We wanted to show her when she was young and bright and ambitious. Scarlett Takes Manhattan tells that story. It’s light and sexy. But, for a reader who is familiar with my work, it has a dark edge.

Rumpus: I’m sure you’ve had plenty of opportunities to do a graphic novel in the past. What made this the right time to do it?

Crabapple: I was lucky enough to have an incredibly supportive publisher approach us who really got what we were doing and gave us total creative freedom.

Rumpus: How did you and John divide the work? Did you basically agree on everything in the story?

Crabapple: Me and John are more in eachother’s business than the traditional artist/writer team. Me and John work out the plot together, he scripts it, he gives me compositional thumbnails, and I make the final art. I’ve got a very melodramatic, angsty sensibility, and he has a much more witty, comedic one, so we really complement each other.

Rumpus: In moving from illustration to comics, did you find working in panels frustrating or restrictive?

Crabapple: The main difference between illustration and comics is that comics are much, much more work. Every comics page is the equivalent of six to nine illustrations. When you hold a graphic novel in your hands, you’re holding artist blood made ink.

Rumpus: How does Scarlett’s brand of feminism translate to the present day?

Crabapple: One thing we wanted to make clear in Scarlett takes Manhattan is that there were not a ton of options for poor Victorian women. Making an “honest living,” which Scarlett initially tries, is impossibly brutal and precarious. Running cons (or performing naked) beats the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory every time. Thank god we no longer live in the 1880s. For everything deeply fucked up about our society, there are jobs for women besides sweatshop worker, maid and whore. However, when I started my own business, I funded it as a naked model. I still think that the sex industry can, for some men and women, be a powerful tool for improving their financial prospects.

Rumpus: Is there anyone in particular who you think comes close to being a modern-day Scarlett?

Crabapple: A real life Scarlett? Well, her aesthetic as about a hundred times more refined, but… if you want someone who went from “The Girl Who Does THAT” to glittering, globe-trotting show-woman on top of her game, you’d be hard pressed to find a better example than Dita Von Teese.

Rumpus: New York City almost feels like a character in Scarlett. What’s your relationship with the city like, and how does it compare to Scarlett’s?

Crabapple: New York’s one of  the few cities in the world that natives still get all romantic about. It’s a brutal ratfuck of a place in a lot of ways, where a middle class person will live like a college student into their forties, and class disparities are in much sharper relief than other parts of the country. But man, for sheer glittering ambition, what could top it? New York makes me swoony and in love. The New York of the 1880s was a place where black eye fixers did a brisk business and people were routinely killed for their shoes. But, the constant aspiration of the city never changes.

the few cities in the world that natives still get all romantic about. It’s a brutal ratfuck of a place in a lot of ways, where a middle class person will live like a college student into their forties, and class disparities are in much sharper relief than other parts of the country. But man, for sheer glittering ambition, what could top it? New York makes me swoony and in love. The New York of the 1880s was a place where black eye fixers did a brisk business and people were routinely killed for their shoes. But, the constant aspiration of the city never changes.

Rumpus: How much research did you have to do for Scarlett? Did you find anything particularly interesting that didn’t make it into the book?

Crabapple: Me and John did a ton of research into the songs, costume design, gambling habits and political literature of the 1880s. Two books deserve shoutouts. Luc Sante’s Lowlife: The Lures and Snares of Old New York and Trav S. D.’s No Applause, Just Throw Money: The Book That Made Vaudeville Famous. We wanted to put in a bit more about Tammany Hall, but ran out of pages. While the nature of Tammany’s scamming seems kind of innocent today—they may have stolen, but at least Tammany never tortured people—the sheer nakedness of their corruption was fascinating. They actually had a publicly sung theme song about how good they were at fixing votes!

Rumpus: Were you able to be as explicit as you liked with the sex in the story, or was there anything you had to compromise for publication/distribution purposes?

Crabapple: We were able to do whatever we wanted.

Rumpus: How big is the overlap between Sketchy’s fans and comics fans? Are you expecting more crossover one way or the other?

Crabapple: I’m lucky in that Dr. Sketchy’s fans are an incredibly supportive bunch who have already been gobbling up Scarlett copies during the presale. What I really hope is that comics fans who have never heard of Sketchy’s dig Scarlett.

Rumpus: Who are some comics creators who strike you as approaching sex in a smart, compelling way?

Crabapple: Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill! Mina in League of Extraordinary Gentleman is one of the best female characters in comics. Moore and O’Neill created a woman who is sexy and intelligent and competent and above all a grown-ass adult, and it translates to how they portray her sex life. In particular, there’s a scene in The Black Dossier that shows Mina and Allan after they have sex. Allan is lying around afterwards with his cock out. It’s done in such an unselfconscious, natural, see-it-every-day way that it flies in the face of decades of comic book prudery and fetishization.

Rumpus: What would it take to persuade you to do comics full-time?

Crabapple: I love comics, but I’d rather cut off my thumbs than do nothing but.

Crabapple: I love comics, but I’d rather cut off my thumbs than do nothing but.

Rumpus: What’s the most accurate thing anyone has ever said about your work? Or the most inaccurate?

Crabapple: It’s not a single quote, but once my painting, “Politics,” got posted on the Something Awful forums. The goons there gave it a smarter, more thoughtful, wittier analysis than almost any art critic had yet given my work. My pet interview peeve? Journalists who write “Sexy naked burlesque artist Molly Crabapple reveals the bare naked truth about sexy sexy sex.” Control the Tourette’s, people!