The poems in The Ancient Book of Hip create a precise and evocative description of time and place; they celebrate that space, even as they have a witty undercurrent of critique.

The poems in The Ancient Book of Hip create a precise and evocative description of time and place; they celebrate that space, even as they have a witty undercurrent of critique.

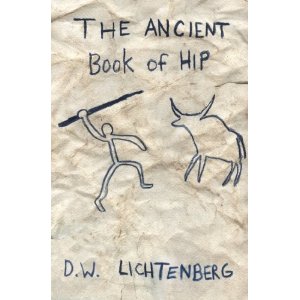

Taking the “Behind the Music” approach to history of events from less than a decade ago, The Ancient Book of Hip sardonically documents the twenty-something zeitgeist of Williamsburg, Brooklyn. They live off their parents, are hipper than you, and have an air of solipsistic entitlement that these poems accurately address. Patton Oswalt has described “the hipster uniform” as a t-shirt intercepted to Park Slope. It has “a unicorn on roller skates saying ‘I’m powered by puppy kisses.’”

Lichtenberg ostensibly has first-hand knowledge of this scene, as his introduction tells. So, the book is envisioned as a document. This explains its strengths and its flaws. The strengths are its ease and confidence, insouciance, and a William Carlos Williams-like urban conversational tone that has tremendous appeal.

As in many books of poetry, tone connects everything. In this case, it delightfully reveals adolescent risk and idiocy. It is concerned with that generations’ morays and its interests. It has a kind of standoffish self-absorption about the project of documenting late-century Brooklyn hipsters.

Read one and you’ve read them all, as there is a monotonous static to them all: “I park my bike in pretty much the same place every day / and my old girlfriend, sometimes / she used to stick little notes for me in the bike chain. // One of the notes said: / Dear smelly, I can smell your smelly bike a mile away. / Smell you later. K.”

An undergraduate workshop would greet this approach to a poem with praise and genuflecting. It does less for sophisticated adults, at least this one. Others in the same vein have done it better. The Ancient Book of Hip has some of the irreverence of O’Hara’s “I do this-I do that” style, but without the devotion to high culture that give those poems their rigor and personality. It has some of the sharp-edges of Ed Sanders’s recent work, but without the unforgettable political comment. It has some of the joy and wonder of Kenneth Koch, but without the adeptness of metaphor, those poems’ glue.

An undergraduate workshop would greet this approach to a poem with praise and genuflecting. It does less for sophisticated adults, at least this one. Others in the same vein have done it better. The Ancient Book of Hip has some of the irreverence of O’Hara’s “I do this-I do that” style, but without the devotion to high culture that give those poems their rigor and personality. It has some of the sharp-edges of Ed Sanders’s recent work, but without the unforgettable political comment. It has some of the joy and wonder of Kenneth Koch, but without the adeptness of metaphor, those poems’ glue.

The poems in The Ancient Book of Hip do a lot with little. They create a precise and evocative description of the time and place that is interesting to Mr. Lichtenberg. They effortlessly praise and celebrate that space, even as they have a witty undercurrent of critique. They are also unashamed of the narrowness of the persona: the white, upper-middle-class; the value of self-absorption; and the theatrical self-loathing. They do nothing with form, line, diction, pacing, structure, allusion, metaphor, rhyme, voice, stanzas, and have no political consciousness. These are things I value in poetry, so if a poem dismisses them, I seek reasons for it; I seek swankiness in other areas to make up for it.

The Ancient Book of Hip is also long (89 pages) as if to make amends for the short, ephemeral nature of the poems themselves. But the book is more concerned with the concept than the line or even the word. I read the book in absolute terms, rather than comparatively. The book says: “In Tokyo I saw / graffiti that said / dance dance dance! motherfucker / so that’s what I did, so that’s what I’ve done / so that’s what I’m doing right now.” The poem, like the whole, celebrates being silly or ridiculous. It is written from impulse, not from rules. It is syntactically uninteresting. It doesn’t take this impossible project, poetry, too seriously; nor is leaden with sorrows and loneliness. But, like McDonald’s, it is all sugar, salt, and starch. It feels pleasurable in the moment, but you feel sick immediately afterwards. The vision of the world, like that of a Billy Collins or a John Ashbery, is one of wonderment; the white man looks out the window and marvels at the colors he sees with clever thirstiness. After some time, though, it becomes dull and predictable. The language doesn’t move. There is no sense of doubleness.

I admire Lichtenberg’s fearlessness to forgo the intricacies of lineation, metaphoric leaps, and the dangers of too much fire or too much ice; he merely says something in a personal way; there is a vivid human voice speaking to me as I read them poems. But questions remain: are poems entertainment? An opportunity for the reader to learn about herself? Are they tantamount to thinking? Are they an intimate connection between reader and writer?

Perhaps The Ancient Book of Hip should be understood more like cultural anthropology or note-taking than as literature; yet when it’s stacked against heavyweights like Robert Hayden, Lorine Niedecker, or Hart Crane, these are imminently disappointing. What happens if you put Wallace Stevens at the Bedford Avenue subway stop in a pink T-shirt from American Apparel? We, the readers, must keep in mind that poems are made. They are arrangements of language and should demand more. Producing poems that are too simplistic can be viewed as a form of fascism that treats readers as one-note consumers who must be condescended to and fed with Styrofoam.

Read “Poem for Dad” by D. W. Lichtenberg in Rumpus Original Poems.

3 responses

D. W. Lichtenberg is my God. He writes like the day is long and lives like it is short.

Sean,

I’m not sure how many times you read this book. I would like to suggest you re-examine The Ancient Book of Hip.

If you put these poems together like a puzzle, I think you will find that they each become more clear, and the longer you spend with the book the more you will get out of them. What you’ve done here is criticized a concept album for having incomplete songs. I repeat: the album is the song.

That, to me, is poetry, and if it can be accomplished without form, line, diction, pacing, structure, allusion, metaphor, rhyme, voice, stanzas, and political consciousness——then it’s that much closer to the source of creation. If that isn’t your goal … why are you writing poetry?

I do invite you to answer this here or directly to me @ karpekarp@gmail.com, or I wouldn’t ask. Thanks.

Big fan of Vegan McDonald’s. Super size me baby!

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment, or log in if you’re already a paid subscriber.