Kay Ryan has been compared to Emily Dickinson, and I like to imagine Dickinson and Marianne Moore reading her with sly commiseration. Unlike some poets with recognizable styles, Ryan does not write the same poem again and again, and her sharp eye is both benevolent and unflinching.

Kay Ryan has been compared to Emily Dickinson, and I like to imagine Dickinson and Marianne Moore reading her with sly commiseration. Unlike some poets with recognizable styles, Ryan does not write the same poem again and again, and her sharp eye is both benevolent and unflinching.

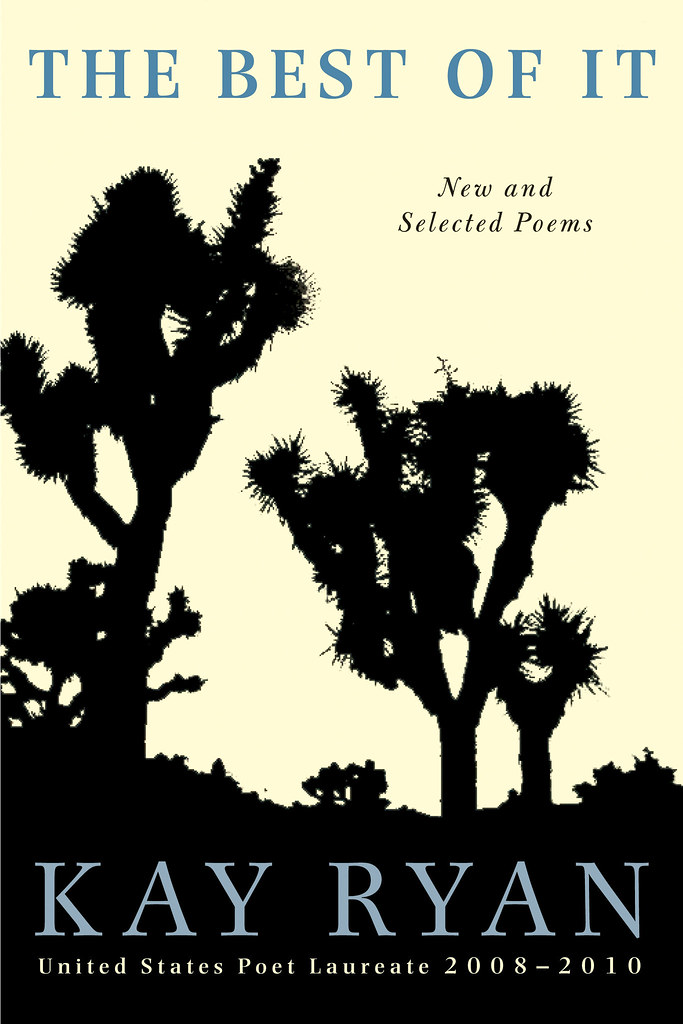

First, I searched for “Virga,” which Kay Ryan read at the 2006 wake for Cody’s Books, Berkeley’ s great independent bookstore. It’s not in The Niagara River, which won a California Book Award in 2005, or in earlier collections. Although an atmospheric scientist is a member of my inner circle, the word “virga” was new to me. It’s a streak of water that evaporates on the way down from the sky, and so does not become rain, Ryan explained. The poem she made of that matter, that phenomenon, still strikes me as a classic example of how her keen curiosity and observations engage with the unusual and beautiful. I briefly looked heavenward after I found the piece in The Best of It, New and Selected Poems.

There are bands

in the sky where

what happens

matches prayers.

Clouds blacken

and inky rain

hatches the air

like angled writing,

the very transcription

of a pure command,

steady from a steady

hand. Drought

put to rout, visible

a mile above

for miles about.

Parsing this is a pleasure, even after repeated reveling in its sounds and shape. The “steady hand” is present, as it is in every poem in this collection, and Ryan is consistently interesting, even in her most bedrock certainties and moments that seem mundane, until she meets them with an open heart and a naturally quirky, compelling intellect.

To say “Tortoise” instead of “Turtle,” the title of the well-known poem that follows, would have changed the tone of what she successfully captures–everyday heroics in other- than- human mammals :

Who would be a turtle who could help it?

A barely mobile hard roll, a four-oared helmet,

she can ill afford the chances she must take

in rowing toward the grasses that she eats.

Her track is graceless, like dragging

a packing-case places, and almost any slope

defeats her modest hopes. Even being practical,

she’s often stuck up to the axle on her way

to something edible. With everything optimal,

she skirts the ditch which would convert

her shell into a serving dish. She lives

below luck-level, never imagining some lottery

will change her load of pottery to wings.

Her only levity is patience,

the sport of truly chastened things

As always, Ryan knows when to be bound and unbound by mastering rhyme without falling into the trap that has undone many “ new formalists” insistent on restrictions they don’t fully comprehend . It helps that her imagery stays fresh, as in the poem that precedes “Turtle.” It’s called “Osprey,” and the last few lines describe the bird returning to hatchlings in a nest, salmon in its mouth:

He fishes, riding four-pound salmon

home like rockets. They get

all the way there before they die,

so muscular and brilliant

swimming through the sky.

Kay Ryan is now the sixteenth Poet Laureate of the United States. She has won the Ruth Lilly Prize, awards from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts and the Ingram Merrill Foundation. A Pulitzer is overdue. She is a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets and the author of six previous books. Not surprisingly, her work appears in dozens of literary journals, from the established, like Poetry, The New Yorker and The American Schola, to younger publications, includingThe Electronic Poetry Review and McSweeney’s.

She has been compared to Emily Dickinson, and I like to imagine Dickinson and Marianne Moore reading her with sly commiseration. Unlike some poets with recognizable styles, Ryan does not write the same poem again and again, and her sharp eye is both benevolent and unflinching, as in “Outsider Art” :

Most of it’s too dreary

or too cherry red.

If it’s a chair,

it’s covered with things

the savior said

or should have said—

dense admonishments

in nail polish

too small to be read.

If it’s a picture,

the frame is either

burnt matches glued together

or a regular frame painted over

to extend the picture. There never

seems to be a surface equal

to the needs of these people.

Their purpose wraps

around the backs of things

and under arms;

they gouge and hatch

and glue on charms

till likable materials —

apple crates and canning funnels—

lose their rural ease. We are not

pleased the way we thought

we would be pleased.

She is not afraid of discomfort, as in “under arms” suggesting underarms and the unpleasant aromas of people who live beyond norms. Outsiders speak to insiders more deeply than insiders might wish, as Ryan states so simply at the end, never losing control of smooth, then jumpy music, or the ability to stretch and compress with well-placed vowel and consonant, as in “ease” and “please” and the stops of “backs” and “hatch. ”

She’s equally fine on the subject of the ultimate insiders, Dutch Masters, in a piece called “Finish,”: “ seeing- in you notice/ when a bruise mars/ a fruit’s surface.’’ Her response to Chagall is as magical as the paintings, making me wish that art critic Michael Kimmelman would revive his practice of being accompanied on museum visits. It’s time he did this with poets, beginning with Ryan.

After encountering her poems, one feels as if one has dined at the table of the host whose guests always say “yes,” to the invitation. The setting will never be artificial, and questions will be important, without pretense, as in “Why We Must Struggle:”

If we have not struggled

as hard as we can

at our strongest

how will we sense

the shape of our losses

or know what sustains

us longest or name

what change costs us,

saying how strange

it is that one sector

of the self can step in

for another in trouble,

how loss activates

a latent double, how

we can feed as upon nectar

upon need.

It would be wrong to present this poem without noting Ryan’s loss of Carol Adair, her long-time partner who died last year. Adair taught full-time at the College of Marin, where Ryan also taught, part-time. Creative people cannot do their best without the rigorous, unconditional sustenance Ryan credits Adair with supplying.

Every United States Poet Laureate has the opportunity to take on a large project that will promote literature. As tribute to Carol Adair’s dedication, and to community college faculty members across the country who labor anonymously, Ryan is launching “Poetry for the Mind’s Joy” with the Community College Humanities Association. She has declared April 1—the beginning of National Poetry Month—National Poetry Day for Community Colleges. This project embodies a spacious democratic urge while also providing an excellent example of how to transform loss.

As ambassador for the joy of fine poetry, Kay Ryan deserves the kind of attention beyond the academy that her position and her choice of what to do with it provide. The Best of It is dedicated “To Carol, who knew it.” Now it’s time for the rest of us to know it or to get to know it more fully. In the words of the late Studs Terkel, another great democratizer : “Let there BE delight! ‘’