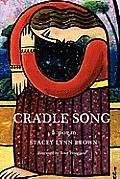

Cradle Song is more than poetry. Stacey Lynn Brown has written a cultural history of the south, of its tenuous and tendentious relationships, of the complicated and often disturbing power struggles between women and men, black and white. Brown’s position in this history, as a young white girl, puts her in the center of these struggles, a privileged victim aware of both her power and its limits.

Cradle Song is more than poetry. Stacey Lynn Brown has written a cultural history of the south, of its tenuous and tendentious relationships, of the complicated and often disturbing power struggles between women and men, black and white. Brown’s position in this history, as a young white girl, puts her in the center of these struggles, a privileged victim aware of both her power and its limits.

I was first exposed to the poems in Cradle Song when I saw Stacey Lynn Brown read at the Miami Book Fair in 2009. When she introduced the book–a long sequence of poems dealing with her life in Atlanta–she spoke about how it’s difficult sometimes to be a southerner, especially in other parts of the country. It’s a feeling I can relate to–some years ago, I mistakenly thought I’d drained the drawl from my voice as if it were swampland to be subdivided and suburbed. It was the result of, as Brown puts it in poem VII, “too much time spent / in front of audiences beaming back / sympathy for the slow-wittedness / implicit in my speech.”

It’s easy, and common, for southerners to get defensive about their/our home region, and that’s not so much because the south has more issues than anywhere else, but rather because 1) we put ours on public display more often and 2) we can’t seem to get past them. The most immediate example of this is Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell’s recognition of Confederate History Month, which initially lacked any mention of slavery, and Mississippi Governor Haley Barbour’s defense of it suggesting that slavery was a “nit” that “didn’t amount to diddley.” As a southerner, I cringe at these moments, and yet I can’t deny my love for the place where I grew up. That’s the ground Stacey Lynn Brown treads in Cradle Song. Brown doesn’t apologize for the south, and she doesn’t even try to explain it, not really. She just tells the stories, sometimes in blunt, plain language.

Cradle Song is aptly named–a poem which attempts this scope can only begin at the cradle, and must end there as well. Lillian Smith, in Killers of the Dream, calls growing up in the south “a haunted childhood,” and Brown captures that feeling. Brown is haunted by the disconnect between the love she feels for Gaither, the nanny she says in poem III

raised me: balling my fists

to teach me to fight, shaming my hips

loose so I could shimmy, count cards

ante up, winner takes all

dozen yo mama’s so uglies on home

and the guilt that comes from knowing that you have benefited from an unjust system. In poem XII, which begins with the first time Brown ever called her father a racist, she notes that “Contempt doesn’t work, as it implies / disrespect I don’t otherwise feel. / And I’m not trying to shame / or indict.” That’s the real difficulty in these relationships. It’s easy to condemn, to point fingers and deride others as backward or ignorant, especially when it’s true. But that’s not the whole story. As Brown said in an interview with Rigoberto González, “It [the south] contains great natural beauty and people who are capable of tremendous kindnesses, but it also contains a deeply entrenched history of racism, bigotry, and prejudice, often within those same people.” It’s hard to feel contempt just for the racist part of a person and not have it spill over onto the rest. But how can one condemn a family member?

Cradle Song isn’t a polemic, though. The poems are beautiful, and painfully honest. They are often direct, but that’s because the subjects are so often disturbing that to make them overly poetic would blunt their truthfulness. They’re also often funny. Poem XXXVII is a phone call from Brown’s mother, who’d just been crowned “The Most Gracious Lady in Georgia,” and who’d been mooned at the ceremony. Poem XIX takes place when Brown was three, and had “just learned to make farting noises / with my hand inside my armpit,” while poem XIII details the nature of southern insults.

But it’s Gaither who really steals the book. Gaither is Brown’s nanny; she drinks, carries a blade, and teaches Brown to “take more pain than I could bear.” It’s this relationship which shows the great contradictions of southern racism, and Brown doesn’t shy away from it. Poem V is an apology to Gaither’s biological daughter.

Forgive me, Pumpkin, Gaither’s true

daughter, for taking her from you

before the sun rose every day

and returning her, spent, at night.

I didn’t know anyone could

love or need her more than I did,

those five days of your motherless week.

That love is absolute, unquestioned. But that doesn’t change the way others see her. From Poem IX:

At a little café in Alabama, she heard

what people had to say about her,

sitting at our table

like she belonged.

That’s the contradiction of racism in the south–the individual is beloved, but the race is despised. That is changing, thankfully, but that contradiction underpins the generational clash on race. Cradle Song is a couple of generations removed from Lillian Smith’s Killers of the Dream, but the world they explore is the same. Brown’s is a bit more hopeful, but no less honest.

Read a new poem from Stacey Lynn Brown in Rumpus Original Poems as part of our celebration of National Poetry Month.