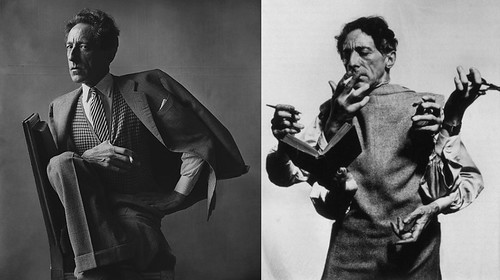

Colette, Sartre & de Beauvoir (facsimiles), Mayakovsky

“Smoking I find the most ridiculous of all the varieties of human behavior and practically the only one that is entirely against nature. Can you imagine a cow or any animal taking a mouthful of smoldering straw then breathing in the smoke and blowing it out through its nostrils?”

—Lifelong smoker Ian Fleming

Historians have long concurred in identifying professional authors as the occupational group most prone to habitual tobacco use.

Writers are most closely associated with the practice of smoking in particular, as if, in the general consensus, the scribe could find inspiration in a tobacco pouch or pry the muse from her hiding-places with a few puffs of poisonous fumes. Other stimulants have found favor among the authorial class; a special example being coffee—Voltaire and Balzac were known to have downed prodigious quantities on a daily basis—but no substance, except for printer’s ink, has been seen to play so important and intimate a role in the life of the workaday wordsmith.

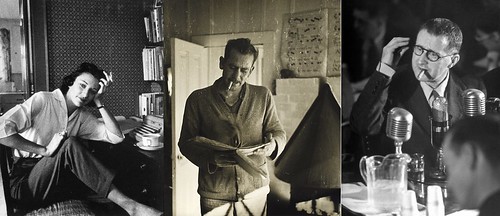

History has preserved only the slimmest visual record of other fads and fashions of tobacco-taking, such as snuff-inhalation and wad-chewing, perhaps because of the unattractiveness and perceived vulgarity of the sniffing and spitting attending these methods of ingestion, although posterity has left many prized examples of sterling silver snuff boxes and gleaming brass cuspidors. Archives abound, on the other hand, with groaning files of photographs of this or that celebrated author taking a deep, satisfying drag from pipe, cigar, or cigarette.

Anderson, Crevel, Gorky

Duras, Dinesen, Berryman

Artaud, Buzzati, Rand

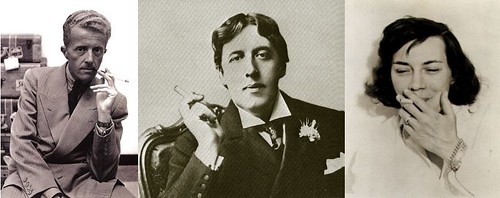

The number of ladies figuring in these smoke-tinged portraits is considerably smaller than that of their male counterparts; a phenomenon which merely echoes statistical findings that smoking is less prevalent among the distaff sex. From Cowper to Colette, renowned writers have championed the joys of nicotine addiction. In long-ago France, Moliere maintained that “whoever lives without tobacco doesn’t deserve to live” while, across the pond, a few centuries later, Oscar Wilde would opine, with customary wit, that “a cigarette is the perfect type of a perfect pleasure. It is exquisite, and it leaves one unsatisfied. What more can one want?”

Dazai, Hurston, Onetti

Cummings, Eliot, Thomas

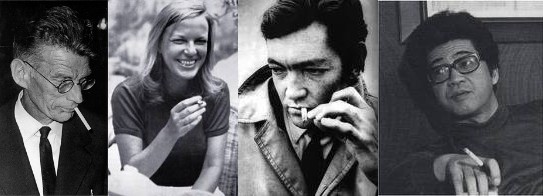

But then there is the sad story of Austrian poet Ingeborg Bachmann (1926-1973): definitive proof against the advisability of smoking in bed. Bachmann met her tragic demise when she fell asleep with a lit cigarette in hand. She may have had the same doctor as Erik Satie, whose advice to patients was: By all means smoke; for, if you do not smoke, someone else will smoke in your place!

Beckett, Bachmann, Cortázar, Abe

Perhaps it is no accident that smoking was introduced to European explorers by native American shamans who used “sacred smoke” as a conduit to visionary experience and spiritual guidance. Legend has it that the American Indian system of inter-tribal communication known as “smoke signals” had its origins in the aerial pictograms formed by figural swirls of tobacco vapor seen during communal pipe-smoking sessions. Certainly, anyone who has ever witnessed smoke balls curling into the air from the tip of a cigarette can attest that, at times, the ghostly patterns made by their fleeting, caliginous coils appear to form letters, even words.

“Time smoking a picture,” William Hogarth

In the dead of night, in a becalmed room, in the solitude of the flickering lamplight, how many writers, while questing after the divine spark, have kept a futile vigil waiting for lightning to strike, vainly watching draught after draught of nicotine-fueled inspiration go up in smoke? Wafting skyward in so many wreathing, spiraling evanescences, who knows what immortal messages, what supernal songs, have strained to be spelled out, only to be lost forever to the remorseless tide of all-enveloping ether…receding wraithlike, into the genie-bottle of the absorbent atmosphere…growing ever dimmer, ever more brittle until, like skeletons on stilts, they steal down the faint and foggy corridors of fugitive Time…

***

History of a Cigarette

by Felisberto Hernández

Translated by Gilbert Alter-Gilbert

1

Late one recent evening I pulled a pack of cigarettes from my pocket. I did this almost without wanting to. I never gave much thought to how many cigarettes I had on hand, or to when I was going to smoke them. It was a long time before I began to think about the spirit of such interactions: of the spirit of man in relation to his fellows; of the spirit of man in relation to things; and certainly I never thought about the spirit of things in relation to men. But without wanting to, I was staring fixedly at a thing: the pack of cigarettes. And now as I analyze it, I recall it vividly. I remember that I had fully intended to pull out one of the cigarettes, but only barely touched it with my finger. Then I began to pull out another, but couldn’t get hold of it firmly, so I pulled out a third. I was distracted all the while—somehow they were able to dominate me a little—yes, it was plainly evident that, along with their scanty material substance, operated a corresponding spirit. And this infinitesimal, discretionary spirit enabled them to orchestrate the escape of some, while I reached for others, instead.

2

The other night I was walking with a friend. Then I became distracted, began to sense something odd, and started thinking about cigarettes. I had the urge to smoke and when I reached for one of them, suddenly I changed my mind and reached for one of the others. Without meaning to, I crimped the tip of the first one I touched, and it seemed as if it had caused me to do this so as to avoid being taken. If given a choice, my tendency has always been, as is only normal, to prefer my cigarettes unbent. Consequently, I pushed the broken cigarette to one side, away from the rest. I offered them to my friend. He reflexively chose the one snuggling in the corner by itself, because it was easiest to reach but, when he saw that it was crooked, he immediately reached for another. I was preoccupied by this series of events for quite awhile but, as we resumed our conversation, I gradually forgot about it. A few hours later, I again felt the craving for a smoke; I pulled out the pack of cigarettes and then it struck me. With much surprise I saw that the twisted cigarette wasn’t there, and I thought I must have smoked it without noticing, and my obsession vanished in a puff.

3

Still later the same night, when I picked up the pack once again, I was confronted by the following: the broken cigarette hadn’t been smoked after all; it had fallen sideways and was lying horizontally at the bottom of the pack. Certain now that it had deliberately eluded me several times, my obsession returned with redoubled tenacity. I was seized by an overwhelming curiosity to see what would happen if I smoked it. I stepped out to the patio, removed all the cigarettes from the pack except the wrinkled one, re-entered the living room, and offered it to my friend; since it was the only one left in the pack, he would have no choice but to take ‘it’. He started to take it, but then refrained. He regarded me with a smile. I asked him, “Is something wrong?” He answered, “Yes, but I’m not going to tell you what…” This really frosted me, but then he added, “There’s only one left and I’m not going to be the one to smoke it.” Then he pulled out his own cigarettes, and we smoked two of them in silence.

4

The following morning I remembered that, before going to bed, I had put the broken cigarette in the drawer of my nightstand. The nightstand bears a special distinction: it has a strange alliance and affiliation with cigarettes. But I was determined not to let this get the better of me. I approached the nightstand, intending to take out a cigarette and smoke it. I opened the drawer. I took out a cigarette as always, with complete naturalness and aplomb but, as I did so, I knocked over a glass of water, and it fell, along with the cigarette, onto the floor. My obsession flared. I quickly contained myself. But when I reached down to pick it up again, I saw that the cigarette had fallen onto a section of the floor which now was sopping wet. This time my obsession was beyond control; it steadily intensified as I observed what was taking place on the floor: the cigarette was blackening along its entire length as the tobacco absorbed the water…

***

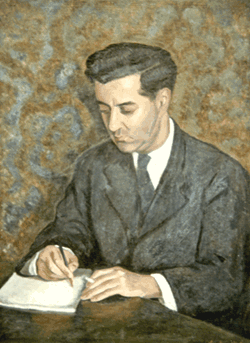

Felisberto Hernández (1902-1964)

Brief Biography by Gilbert Alter-Gilbert

A Uruguayan writer of growing reputation, Felisberto Hernández was born in Montevideo, and spent most of his life in its environs. Early in his adult life he supported himself as an itinerant pianist, traveling throughout Uruguay, Argentina, and Brazil playing in silent movie theaters and giving private recitals in wealthy homes where, it is presumed, he met an abundant supply of ample-bosomed, matronly women which gave rise to the rumor, whether baseless or deserved, that he had an amorous obsession with corpulent women, and enjoyed a succession of dalliances with them. Certainly there is evidence that, as Hernández advanced in years, each of his numerous wives and female companions seemed better nourished and more graciously endowed with adipose tissue than the last.

A composer as well as a pianist, Hernández gave concerts featuring both his own works and those of such contemporaries as Igor Stravinsky. Hernández’s fast, agile fingers enabled him to ply two trades—that of musician and that of stenographer. He developed a stenographic system of his own which was highly innovative and efficient and he even wrote stories using it which were found, unpublished, at the time of his death—but no one has been able to decipher them!

Hernández’s customary poverty and vagabondage were alleviated somewhat by his association with a circle of major Latin American intellectuals. After 1940, he gave up piano-playing to devote himself to literature full-time. He traveled to France in 1946 and spent two years there, forming a close and lasting relationship with distinguished author Jules Supervielle, who presented him at the Pen Club in Paris and at a Sorbonne lecture hall.

Hernández is often cited as a forerunner of magic realism both because of the fanciful transgressions of his imagination into quotidian existence and because his stories abound with static objects which seem to be invested with a restless, interior life of their own. His fabulistic fiction has been described as a “strange and fascinating blend of realty and dream, ironic observation and poetic fantasy.”

[In English: Piano Stories (out-of-print) and Lands of Memory.]***

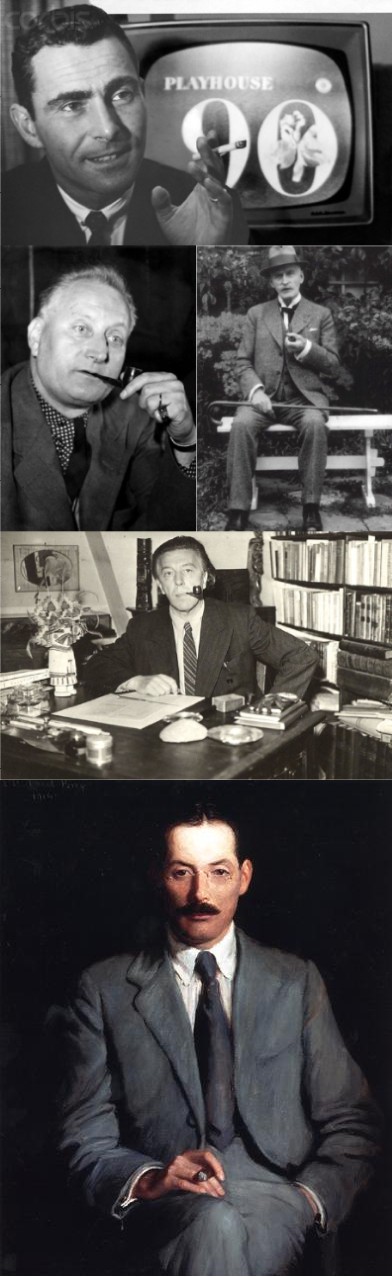

Serling, Giono/Hamsun, Breton, Robinson

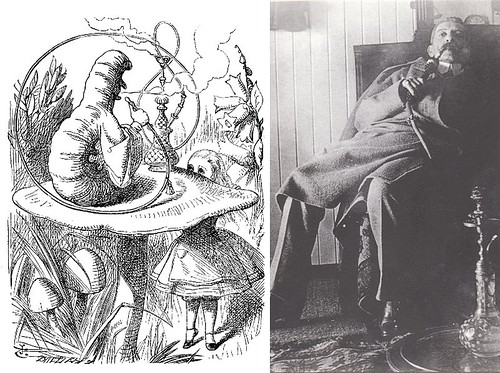

Hookah-Smoking Caterpillar, Alice, Hookah-Smoking Pierre Loti

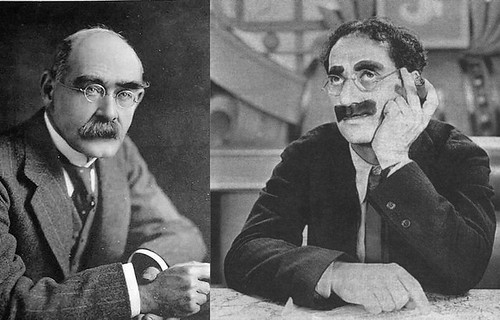

The definitive smoker chic look anticipated by Rudyard Kipling two decades before Groucho Marx perfected it with a fine Cuban cigar.

***

More posts by Gilbert Alter-Gilbert on A Journey Round My Skull:

—Of Goose Quills, Gloves, and Writing Booths

—Poets Ranked by Beard Weight

—Soap Opera Digest: A Candybox of History’s Sappiest Literary Lovers

—Interview 1

—Taedium Vitae

–Snake-O-Rama: one, two

Lions of Literature:

Leon Bloy

Swinburne

Adelheid Duvanel

Christopher Spranger

4 responses

We do need to be reminded at times of the universality of the cigarette in literature, in film, in daily life as it was. It’s being erased from the modern landscape. It is common today to vilify the smoker; imagine some of our greatest writers (Highsmith, Wilde, de Beauvoir) chomping away on nicotine gum instead, or slapping their patches on before sitting down to write. At least it’s still okay to drink publicly- or is it?

Wonderful photos in your article–“Nicotine Chic: Writers as Smokers”

Makes me think again of contending claims about John Nicholas Beffel. R. S. Calese maintains Beffel was a nonsmoker. Francis Russell says Beffel was a chain-smoker. Which is it?

Hi

Stumbled upon this while doing a little research about cigars. Nice post, very interesting. Malcolm Gladwell talked about smoking in The Tipping Point. He said something along the lines of (paraphrasing) ‘maybe kids don;t smoke because smoking is cool, but cool people smoke.’ It made sense in context. Writers are cool people, so…

My question is: What famous writers did NOT use Tobacco during the 20th century?

It seems to me that there is no information regarding this matter, as there is only evidence of writers who were born before the 20th century, that publicly shunned tobacco: Tolstoy, Hugo, Rousseau, Voltaire and Balzac + Heine (according to one doubtful source).

And also: Do you know if there is any case of a creative writer that did not do any kind of mind altering substance (not even coffe as a fuel for the creative process)?

Speculation: Altough Kafka did not drink according to a personal quote of him, he also seems to be a “sober soul” in general, but I have not found any evidence that he would abstain from other drugs (such as tobacco and coffe). He did suffer from mental health issues obviously, so his mind was not “Sober” per se.

This is of great interest to me since i think it´s kind of a depressing fact of life if Intoxication is requirment for artistic potential, as Nietzsche once claimed.

Since no writer would have been able to smoke before atleast 1492, there is nothing that says Smoking Tobacco is a “necessity” to become a “creative”author of course (ask the writers of the Antiquity and the Medieval era). But it seems to me that the 20th century culture around writing and famous authors goes hand in hand with alcohol and especially tobacco, almost as a branded cliché of the self-destructive “genius”.

Speculation: I would not be surprised if the tobacco companies paid the publishers and authors to glamourize smoking and promoted it´s use in public relations during the 20th century (as they did with Hollywood), but of course a whistle-blower would have exposed this, so i am almost certainly wrong.

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment, or log in if you’re already a paid subscriber.