How do you supersize a Rumpus Original Combo? That’s easy—just take a book review and an interview with the author, and add a Rumpus Original Poem to it!

How do you supersize a Rumpus Original Combo? That’s easy—just take a book review and an interview with the author, and add a Rumpus Original Poem to it!

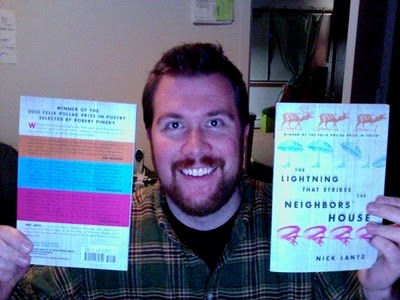

Nick Lantz won the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference Bakeless Prize for his book of poetry, We Don’t Know We Don’t Know (Graywolf Press). His second book, The Lightning That Strikes the Neighbors’ House, was selected by former U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Pinsky for the Felix Pollak Prize in Poetry (University of Wisconsin Press). Nick was the 2007-2008 Jay C. and Ruth Halls Poetry Fellow at the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing, and is the recipient of Gettysburg College’s 2010-2011 Emerging Writer Lectureship.

The Rumpus: With contest submissions often exceeding a thousand, you manage to win the Bakeless and Felix Pollak Prizes in the same year—congrats on the publication of We Don’t Know We Don’t Know and The Lightning That Strikes the Neighbors’ House! Although We Don’t Know We Don’t Know is technically your debut, I suspect it contains the more recent work. Did you complete one manuscript before starting the next, or was there some overlap between the two? Can you talk a little bit about what distinguishes each project, as well as how long the manuscripts were in circulation before you received the good news?

Nick Lantz: We Don’t Know was taken very quickly, all things considered. I finished it around August 2008, sent it out to contests that fall, and got the good news from Bread Loaf in early 2009. The Lightning took a bit longer. It’s the much-revised remnants of my MFA thesis, and it had been collecting rejection slips since 2005. A poem in that book alludes to the Ship of Theseus, a boat that was supposedly maintained over many years by replacing its parts piecemeal as they deteriorated, begging the question of whether it was still the same ship, and, if not, at what point it ceased being that original ship. That’s how I feel about The Lightning. If you were to dig up my actual MFA thesis (please don’t), you’d see only a handful of the original poems. With The Lightning, I worked from the poems up. I was figuring out what that book was about as I assembled, disassembled, and reassembled it.

With We Don’t Know, I worked in the opposite direction—I had the book title and sections titles and the general theme before I wrote a single poem, though of course it did change as it came together. As a result, the writing process of We Don’t Know was much more compact—maybe nine or ten months—and (almost) all of the poems in it were written for it, that is, with their thematic/formal connection to the manuscript in mind. Because of the time-frames involved, the poems in We Don’t Know feel more like part of a set, because they were written at more or less the same time.

The Lightning contains poems I wrote in the first semester of my MFA program all the way through a poem or two that I slipped into the book right before I sent it to the publisher. I see more of what I’ll diplomatically call my development as a writer in that one. There are poems in the book that I just wouldn’t write today—I still like them, but I just wouldn’t write them anymore. And there was definitely overlap between the two books. While they are very different collections in some ways, there were a handful of poems that really could have gone either way, into either book, and I did a lot of last-minute agonizing about which ones would end up where.

The Lightning contains poems I wrote in the first semester of my MFA program all the way through a poem or two that I slipped into the book right before I sent it to the publisher. I see more of what I’ll diplomatically call my development as a writer in that one. There are poems in the book that I just wouldn’t write today—I still like them, but I just wouldn’t write them anymore. And there was definitely overlap between the two books. While they are very different collections in some ways, there were a handful of poems that really could have gone either way, into either book, and I did a lot of last-minute agonizing about which ones would end up where.

Rumpus: We Don’t Know features four subtitled sections; The Lightning contains three parts. How do you tackle book-length organization? How do such sections help frame the work?

Lantz: Back when I was an MFA student, the poet/fiction writer/memoirist Jesse Lee Kercheval suggested that I think about section breaks as a device for emphasizing particular poems. Maybe this is intuitive, but I hadn’t thought of it that way—I’d mostly thought of sections in terms of thematic groupings. But now I like to think of section breaks as the equivalent of line or stanza breaks in a poem. They create a pause, a breath, and they also put a little bit more weight on what comes before and after them. They’re a way of generating rhythm on the macro-level of the book, and the poet can subtly direct the reader to key poems by controlling their placement within those sections. An extreme version of that is the second section in We Don’t Know, which contains only one poem, “Will There Be More Than One ‘Questioner’?” That poem was one of the stranger poems I’ve written, and I wanted it to stand by itself within the manuscript. It certainly needs some breathing room on either side of it, and putting it in its own section was a way of achieving that.

Beyond that, organization for me usually amounts to spreading things around evenly. If I have two poems that mention dogs, say, I don’t want those poems next to each other. And I try to alternate tone and length, when possible. If I have poems that are part of a series, I try to space them out. In a few cases, though, I’ve had poems that I really wanted in a particular spot in the manuscript because of something specific the poem did. The last poem in We Don’t Know ends mid-sentence, and I knew pretty early on that I would end the book with that poem, just because I liked the idea of ending a book mid-sentence. For a similar reason, “The Last Words of Pancho Villa” was variously the first or last poem in The Lightning in earlier drafts, though in the final book, it’s the penultimate poem.

Rumpus: Lightning’s sections emphasize place as do titles of poems such as “U.S. Route 50, Nevada, The Loneliest Road in America,” “The Aging Sci-Fi Actor Speaks to Third Graders at the Local Planetarium,” and “The Soul Diva, Past Her Prime, Visits the Holy Land.” What’s funny (and fantastic) is that in the case of your poetry, titles most often act as the primary—if not sole—sources of narrative stability. Throughout the collection, imagination rebels against physical and temporal confines. Is place more than a jumping-off point, something acknowledged only to be abandoned? Is the act of anchoring readers via titles a deliberate one?

Lantz: Well, geography has always been a resonant thing for me. I grew up in California, which contains about every biome and geographical formation imaginable. Mountains, valleys, forests, coasts, bays, lakes, rivers, estuaries, high desert, low desert, grasslands, chaparral, and on and on. The utter bigness of the Sierras, for example, just imprints itself on you. Death Valley is punishing and beautiful like nothing else. These are the things I think about when I’m staring out at the dingy, weeks-old snow in Wisconsin in January. As far as I’m concerned, the Midwest doesn’t have geography; it has weather. And looking through my poems, I can see the point where I started writing more about weather than geography.

I do often, and very consciously, use titles to situate a reader in a particular place, even if I’m going to abandon it quickly. Or, more broadly, I often use titles as a dumping ground for exposition or information that I want to keep out of the poem itself. With all three poems that you mention, I want the reader to know the starting point going into the poem. I certainly use abstract titles just like any other poet, but expository, situating titles have always attracted me ever since I read James Wright’s “Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota” for the first time. I’d also be lying if I didn’t admit to loving titles that are on the flashy side. Matthea Harvey’s Pity the Bathtub Its Forced Embraced of the Human Form may just be the best book title ever. Ever. Though I’ll allow that there are occasionally good reasons to leave a poem untitled, generally speaking, if you don’t have a good title for a poem, you don’t have a good poem yet.