“As a writer, I’m interested in trying to get to the complexity of experience. For me, that has led—in poetry—to counterpoint, polyrhythms, and clausal layering.”

“As a writer, I’m interested in trying to get to the complexity of experience. For me, that has led—in poetry—to counterpoint, polyrhythms, and clausal layering.”

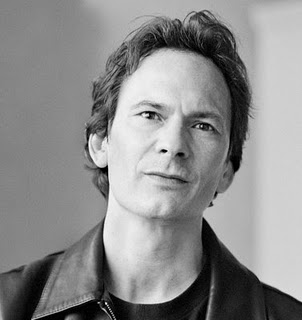

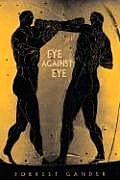

Born in Barstow, California in 1956, Forrest Gander is an American poet, essayist, novelist, translator, and critic. His work includes the poetry collection Eye Against Eye (New Directions Press, 2005), the translation Firefly Under the Tongue: Selected Poems of Coral Bracho (2008), and a collection of essays, A Faithful Existence, published in 2005. His honors include fellowships to the Whiting, National Endowment for the Arts, Guggenheim, and Howard foundations and a PEN Translation Award. Most recently, he has accepted the Writer-in-Residence position at Florida Atlantic University. Parts shape-shifter, parts geologist, Gander shares his aim at crossing genre in hopes of transcribing experience, situation and place, and in this interview shares his insights on his most recent work. Gander seeks out the physical history of being human within its natural process. For Gander, the language is hidden not only in the shifting, and not only in the movements, but within the in-between spaces. There are no blank spaces–only possibility.

The Rumpus: The movement of your novel, As A Friend, paragraph by paragraph, seems to move similarly to that of a stanza or verse in poetry. Additionally, the movement of the exposition (particularly when in third-person) seemed to move similarly to that of stage directions in a play. Was this commingling of genres intentional, or were they more of an effect brought on by the aim of your aesthetic project?

Forrest Gander: It took me a long time—close to twenty years—to write this small novel, to learn how to apply to prose everything I’d learned as a poet. But even in my poems, I’ve been interested in crossing the borders of genre. The section of my novel called “Sarah’s Tale” is considered by some people to be the most poetic, and yet I think of it in connection with the prose of David Markson or the procedural statements of Wittgenstein.

Forrest Gander: It took me a long time—close to twenty years—to write this small novel, to learn how to apply to prose everything I’d learned as a poet. But even in my poems, I’ve been interested in crossing the borders of genre. The section of my novel called “Sarah’s Tale” is considered by some people to be the most poetic, and yet I think of it in connection with the prose of David Markson or the procedural statements of Wittgenstein.

Rumpus: A title such as Eye Against Eye (I against I, possibly?), the Edmond Jabes’ epigraph at the beginning of to your novel, particularly the last two lines: “the friendship of a stranger become our double, adversary and accomplice,” and the differing yet interchangeable understandings of the character Les by Clay, Sarah (and even Les himself for that matter) in As A Friend, hints at the idea of an alter-ego, or other, of Forrest Gander that is at play; a relationship that at times appears to take place in real-time as a piece progresses. Do you view yourself (as writer) as both adversary and accomplice? Do you see the reader/writer relationship as being one adversary and one accomplice? Or both?

Gander: Don’t you think that to be a human being at all is to be engaged with others, to be involved, invested—even if we’re monks—in a world, a language, etc. that we can’t claim to have created? As a writer, I’m interested in trying to get to the complexity of experience. For me, that has led—in poetry—to counterpoint, polyrhythms, and clausal layering. In the novel, I wanted to explore valences of friendship: eroticism, jealousy, emulation, compassion. Like my readers, I’m very likely a congeries of contradictory and shifting selves.

Rumpus: You write in your novel: “I don’t think poets tell things at all, you said. Poetry listens.” Or, could you talk a little more about that as it relates to your own poetry?

Gander: At least in my practice, poetry is connected not only to music but to silence—which is why I think so many American readers are baffled by it. And for me, poetry comes about through attentiveness, what Simone Weil calls prayer and what Miles Davis calls not just listening, but “listening into.” Essays tell about things. But it seems to me that poetry is a kind of tuning to situation and place, to the felt rhythms and lexicon and syntax of a particular engagement and stance.

Gander: At least in my practice, poetry is connected not only to music but to silence—which is why I think so many American readers are baffled by it. And for me, poetry comes about through attentiveness, what Simone Weil calls prayer and what Miles Davis calls not just listening, but “listening into.” Essays tell about things. But it seems to me that poetry is a kind of tuning to situation and place, to the felt rhythms and lexicon and syntax of a particular engagement and stance.

Rumpus:: It appears that each character section of As A Friend reflects each form of writing you’ve adopted; Clay/Fiction, Sarah/Poetry, Les/Non-Fiction, with translations woven in across some of the sections. Was this a conscious strategy?

Gander: Whatever we come to call a “feeling” for a character comes—at least for me—as measure, a rhythm of perception and response. I was looking for the form for the emotional conditions of the different characters. I was thinking about their bodies, the way they would move through a space. It wasn’t important to me to establish clear realms of poetry, fiction, and non-fiction, but I felt I had every genre to draw from.

Rumpus:: There’s a passage in Michael Ondaatje’s Divisadero that reads: “In the past, Rafael had traveled from village to village, argued a salary, invented melodies, stolen chords, slashed the legs off of an old song to use just the torso–but he had come to love now most of all the playing of music with no one there. Could you waste your life on a gift? If you did not use your gift, was it a betrayal?” Would you say that Les spent his short life using his own gift? Because he could no longer use his gift, or rather, once his gift became exposed to his wife and Sarah, could his suicide be read as “collateral damage” to Clay’s betrayal rather than Les betraying the other characters? If Les had chosen the straight and narrow, would he have betrayed himself?

Gander: Ahh, those are just the questions I hope the book provokes and I feel a whelm of gratefulness that you have articulated them.