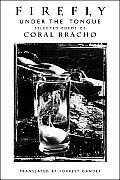

Rumpus: In the introduction to Coral Bracho’s poetry collection Firefly Under the Tongue, you write that if one tries “to put [their] finger on the meaning of a poem, the meaning seems to move elsewhere, and so [one] begins to focus on feeling the poem, engaging it as an active movement taking place on the page and also in [one’s] mind” (XII). Do you share that same approach in your own translations? Instead of hollowing out the meaning of the words, do you search for a feeling instead? A texture? An impression?

Gander: Texture, impression, feeling, meaning: to sliver away any of these aspects in a translation is to diminish the work—and that’s not only a literary failure but an ethical one. It’s a very mysterious process, translation. The translator must disappear into the original, must absorb the music of another’s mind. And then the translator must return full force, with everything she has ever learned about the art itself—about poetry if it is poetry she is translating. In its iterative obliterations and reincarnations, it’s much more a spiritual than a transcriptional activity.

Gander: Texture, impression, feeling, meaning: to sliver away any of these aspects in a translation is to diminish the work—and that’s not only a literary failure but an ethical one. It’s a very mysterious process, translation. The translator must disappear into the original, must absorb the music of another’s mind. And then the translator must return full force, with everything she has ever learned about the art itself—about poetry if it is poetry she is translating. In its iterative obliterations and reincarnations, it’s much more a spiritual than a transcriptional activity.

Rumpus: Native speakers of a particular language (i.e. Spanish), who attempt to translate a language similar to their native language (i.e. Portuguese), have a tendency to push the language through an assembly line of Portuguese to Spanish, followed by Spanish to English. When you read in Spanish, do you think in Spanish, or do you read Spanish and think in English?

Gander: In Spanish, I am someone else. The Mexican children call me Bosque, which means forest. I have a different rhythm to my thinking and speech. I talk in ways that, if they were plotted on some graph, wouldn’t correspond at all to my speech in English. I’m thinking in a modality distinct from my thoughts as an English speaker.

Rumpus: In your interview with Mario Hibert, you speak about how you think scientific language changed by embracing uncertainty; a parallel that also exists in poetic language. You mention being interested more in the “inquiry of capturing and articulating truth,” rather than pretense. Do you see translation as its own language?

Gander: Hmmm. If I say I’m trying to capture and articulate truth in that interview with Mario Hibert, there might be a mistranslation involved. I don’t really know what people would mean by “capturing truth.” Maybe it’s like capturing an electron. I’m not a relativist. I think we can say that this happened. The Holocaust happened. My father died. But I’ve got no choke hold on truth and certainly not THE truth. In fact, the intention in my work is to get at some of the fullness of experience, what Hopkins called the dappled nature of the world, some range at least of its varied and simultaneous tonalities and implications.

Rumpus: How does one’s poetic sensibilities evolve when discovering another language? How has your writing–and translations for that matter–evolved?

Gander: I’ve always been drawn to translations. Before I read the 19th century English novelists, I’d read the French and Russian ones in translation. Languages tune not only our ears but our minds in different keys. Certainly the work I have translated has penetrated my body and mind so deeply that the work I’ve written afterwards has been transformed in very specific ways that are sometimes obvious at least to me. Coral Bracho’s work stands as one example. Her slippery syntax provided me with possibilities I might not have imagined otherwise.

Rumpus: Some have referred to you as a “southern poet” or “poet of the south.” Outside of the obvious, geographical connotation, what exactly do these references imply? Is it aesthetic or thematic? Is it custom or culture? Is it simply voice? Do you see yourself as a southern writer, and—if so—in what ways?

Gander: My family has deep Virginia roots: Robert E. Lee, Lord Fairfax, we landed in Virginia with the first English ships and never left. I’m the only one in my family to leave the state. Growing up and going to camp in Rockbridge Baths, majoring in geology at William and Mary, collecting specimens of the state fossil, Chesapecten jeffersonius, along the James River—I was profoundly imprinted by Virginia’s landscape. Like A. R. Ammons who left the south but was forever marked by it, I’m a Yankee now but the landscape to which my heartstrings are tied is nine hours drive south of where I live. In terms of aesthetics, those old regional differences are quickly changing. I don’t think we can simply claim that Southern writers are formally conservative champions of the farmer as exemplar of “the true man” anymore, if ever we could.

Rumpus: Poetry paired with photographs might be seen as another form of translation. How do you view the relationship between the two, and do you see the poems and the photographs as inextricable from one another?”

Gander: Hopefully, the poems work as poems on their own, and the photographs as photographs. But together, maybe they give rise to something more powerful yet. Maybe they call new ways of seeing and feeling and thinking into being. Out of their mutuality. My new book, Core Samples from the World—it won’t come out until 2011—is a series of collaborations with three photographers, the great Mexican master, Graciela Iturbide, and two remarkable North Americans, Raymond Meeks and Lucas Foglia.

Gander: Hopefully, the poems work as poems on their own, and the photographs as photographs. But together, maybe they give rise to something more powerful yet. Maybe they call new ways of seeing and feeling and thinking into being. Out of their mutuality. My new book, Core Samples from the World—it won’t come out until 2011—is a series of collaborations with three photographers, the great Mexican master, Graciela Iturbide, and two remarkable North Americans, Raymond Meeks and Lucas Foglia.

Rumpus: Do you, or the photographer, feel it necessary to “fill-in-the-blanks” so to speak? Is that what’ s taking place, or is it simply two sides to the same conversation? Is it a conversation, or a debate? Once both are viewed together, when taken apart after the fact, is something imminently lost?

Gander: No blanks. The empty spaces and the silences are active zones. So neither photograph nor poetry is a crutch for the other. What I hope is that each is a catalyst, altering and reshaping potentialities. Each becomes different the way your lover becomes different when you are together or separate. Not lesser, but otherwise.

***

This is a Rumpus Reprint and was published originally in Coastlines.