Stars of the Night Commute is a tremendous first book by a poet who has been publishing for some time now… One distinctive feature of Božičević’s work is that her poems work well together, that is, not only telling stories individually, but also in the form of several series.

Stars of the Night Commute is a tremendous first book by a poet who has been publishing for some time now… One distinctive feature of Božičević’s work is that her poems work well together, that is, not only telling stories individually, but also in the form of several series.

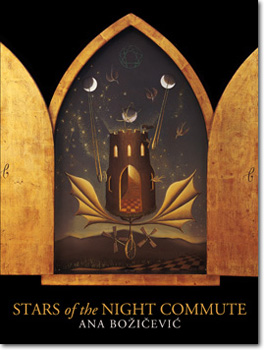

On the cover of Ana Božičević’s Stars of the Night Commute, a tower is lifted by the crescents of two luminous moons, hanging from them by two straps that are connected to its surface by wheels. The night sky is filled with stars. The tower resembles some kind of contraption, a ‘pataphysical machine perhaps (a machine of the possible). This scene is the painting ‘Icono’, a fantastical triptych by the female para-surrealist painter Remedios Varo (1908-1963), enclosed by two wooden panels. And in the same way that the panels open up to the scene of the tower, the tower invites the reader in to a similar world of wonder and fragile irony.

The image invites you in not just because it is the book’s cover, but because both the painting and Ana Božičević’s poems capture similar sensations; that of the distant but imminent, blazingly luminous, yet nocturnal commute. Like the painting, the poems in this book, both in themselves and as a whole, form wondrous stories. In a sense they are failed stories, stories that tried to be, but are reshuffled by a secret that leaves them incomplete, for (to paraphrase Leonard Cohen) they are cracked open to let in a glowing light.

Stars of the Night Commute is a tremendous first book by a poet who has been publishing for some time now. Divided into three main sections – ‘The Stars on the 7:18 to PENN’, ‘Night Passengers’, and ‘The Long Commute’ – it collects poems from four previously published chapbooks. One distinctive feature of Božičević’s work is that her poems work well together, that is, not only telling stories individually, but also in the form of several series. This in turn means that the book as a whole is a very open yet coherent collection (reminiscent in this sense of Jack Spicer’s serial poems).

The poems themselves typically have a fragmented narrative quality to them and do not usually come full circle. These poems might be seen, not primarily as linear, but as constellations of ideas that have body and dimension as well as being open and porous, like a cloud, or a fluffed-up ball of cotton, and indeed in ‘Ode to Cotton’ we read, “The catch in your breathing – / a white bit of cotton…Hope lives in the cotton: // and I could pray to cotton.” These lines are quite typical for Božičević. A gentle sincerity that invokes a sense of the holy in simple everyday objects and situations. Here is an example from the final section:

i. Rhode Island

From water and wood

you build on the jetty

a shrine, and place

1. an acorn

2. a button

on the salt-worn planks.

(O traveller. Grey star.

From your hat, when you upend it,

your small family upturn their faces.)

And morningly

nebulae, red-throated

waterbirds,

typestrokes of

fish

visit the shrine

(to view the film

of a coat, departing).

Eileen Myles writes in a blurb, ‘[I]n poetry at some point you don’t know what the writer means. In Ana’s work I watch ‘it’ vanish (all the time) & I trust it.’ Now I wouldn’t say that in all poetry you at some point don’t know what the writer means; but I completely agree that reading Božičević’s poetry can feel like something is vanishing before your eyes.

However, these fleeting moments are not allowed to slip out of the poem (letting the poem collapse), but remain caught inside of the poem, like flickering fireflies in a glass jar (or like ‘typestrokes of / fish’). The poem does not slip away from you as if in quicksand, but invites you in amid the vanishing. Here is a typical example; part one of the eight-part poem ‘Some Occurrences on the 7:18 to Penn’:

He showed me this book called ‘Discovering God.’ And guys?

I nearly did choke on the swanning spray of insufferable light –

‘Some people can only take seconds

of God’s voice’, he said. But for me

it was, like, the rubbery-awake I get after a slap,

or (not that I did that in a while) after I

write a poem, then open the window

to the naval dawn air.

I see a hawk being chased by sparrows.

And I won’t ever again write simply again

‘cause I won’t ever feel

the simplicity of an again bloodthirsty

sparrow.

Oppositions abound in these poems. The general tone is light and playful, often characterized by a specificity and intimacy that is reminiscent of Frank O Hara’s famous style of incorporating names, times and dates in his poems. In Stars of the Night Commute there are specific sites like a train commute on the 9:17 train to PENN, sections devoted to particular characters (God, Amy, Sebastian). “Amy / there is a swan in your breathing / there always is,” and in a next poem: “you and I are servants of birds.” This makes the poems very local and contemporary. In one poem God is accompanied by two emoticons, in another ‘God is President, She’s Rose of the World’. But the appearance of God as a female president illustrates that Božičević is not averse to interweaving layers of socio-political critique. And intimacy here goes hand in hand with distance and various allusions to conflict. “WHAT PASSES FOR EUROPE // BOMBS. JUST LIKE US PASSING FOR LIGHT.”

Ana Božičević, we are informed, was born in Zagreb, 1977 and emigrated to America in 1997: short factual statements that hint at a much more complicated history. In any case, America is probably as good a candidate as any to take in the impact of these poems. For what is America for better or worse, if not – just like these poems – a blooming place of endless contradictions, constant becomings of “almost America,” just like out of these poems stars bloom and poetry is no longer remote, yet continually on the move. “The flower of the mouth. In language the earth blossoms toward the bloom of sky,” writes Heidegger. And Ana Božičević replies:

Listen: stars are blooming.

Out of me. And I’ve become a blooming place. Almost

America –