In A Meteorologist in the Promised Land, Becka Mara McKay reminds us that every language is a unique translation of a combination of desire and thought, both of which have complicated, individual histories.

In A Meteorologist in the Promised Land, Becka Mara McKay reminds us that every language is a unique translation of a combination of desire and thought, both of which have complicated, individual histories.

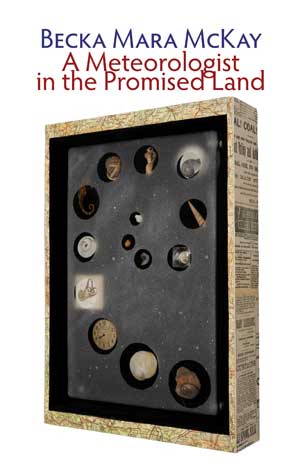

Becka Mara McKay has an MFA in translation from the University of Iowa, and her translations of Hebrew fiction, her energetic engagement with what English and Hebrew and all language must do, inform every word in her first poetry collection, A Meteorologist in the Promised Land. The title itself has layers of meanings, between the promised land and its implications from the Old Testament to the Civil Rights Movement, to the infinite spaciousness of the word “meteorologist,” and its uses.

While a meteorologist can (duh!) forecast weather for a civilian population, a meteorologist I know makes mathematical models that help illustrate global warming patterns. There’s potential for poetry in both occupations. A meteorologist can also work for an army, providing information about the best time for helicopters or other tools of war to take off, land. collect intelligence, collect and assist wounded, wound and kill. The helicopters appearing later in this book add oddly effective ballast to earlier pieces such as T’philot –(Prayers : Jerusalem, summer):

1. For Vesalius

Jerusalem is Rome ecorche Skinned city

Teaching anatomy

in her eyeless tomb.

Peeled, the body reveals

nothing. Tendon plucked from muscles,

muscles cleaved from bone.2, For the Galilee

The Kinneret cannot roll

like her sister does. She sings

in fractured slate.

McKay reminds us that every language is a unique translation of a combination of desire and thought, both of which have complicated, individual histories. Poetry influenced by immersion in other languages and cultures can contain a rich, sometimes prickly sense of expansion, as McKay’s does. Think of a kind of baptism of expression, as in the real and symbolic elements in the waters of a font or a mikve, the Jewish ritual pool. When Jerusalem is compared to Rome, mind and soul take off in elevating and challenging ways, some of which are contemporary and political and at the same time, eternal . When slate fractures, it makes many patterns and can’t be put back together again without enormous effort, the evidence of breakage impossible to disguise. This is an effective and necessary image for the Middle East itself.

The passion and force in these pages is unrelenting, and more often than not, truly original. In “The Excision Sonnets” she declares that

“it is dangerous to want so badly.” And then she illustrates want and need and the spaces between with visual and verbal elegance that yearn to be memorized.

In #6 she specifically invokes prayer, which is interesting because this is a book that could legitimately, be called “SIDDUR,” which is the term for a Jewish prayer book, but has its root in the word ‘’seder,’’ which means “order” which is what all languages attempt. McKay’s immersions and allusions are breathtaking, vital and true.

“Cosmology was beauty school for the Milky Way,” is the last line of “Epithalamium (in seven disciplines).” Like every other poem in this book, it can be read for surface interest as well as for subterranean, linguistic or spiritual sustenance.

She wonders

does minimal

mean irreducible?

is the minimum ever sufficient?)

The poem in which these issues are raised is called “Queries,” and they are made especially crisp because Hebrew is a very compact, active language, a fact McKay grasps with assurance. Any reader interested in the powers and varieties of tools of expression, or whose native tongue is English without a lot of conscious exposure to other vernaculars, will also come away from McKay’s work with a fresh sense of poetry’s possibilities.

“I’d like a better word for waiting, but attend is too expectant and expect is too smug,” is the last sentence that introduces a group of prose-poems.

From 1. We Are Perfectly safe in Jaffa (Daytime) :

Later that same day we find ourselves on the beach, the best place for watching the helicopters, unless you don’t want to see the heavy artillery slung below their bellies like sharp-edged lamprey nearly ready to drop off and find another shark’s guts to vacuum.

The lines above deserve to be compared to the superb Vietnam reporting by Neil Sheehan and others of his caliber, further proof that the boundary between the finest, most urgently wrought poetry and prose can sometimes disappear, to be declared, simply, essential speech. The piece continues:

Children white in the sand. Some of their mothers are between cigarettes; some of their mothers are between geographies, always knowing that the words compass, conscience and north are related. These mothers drop their cigarettes in the surf and wade with the patience of the dead to retrieve their children from the waves. Their mothers are the color of butter, the color turtle beans. The color of Sabbath wax. The color of Jerusalem stone. The color of dirt in Missouri.

To leave off the last sentence would be to perform a kind of maiming. “Missouri” broadens the reach of every preceding word, in part by connecting Israel to the United States in a way that is confrontational without being surly.

The sixth poem in this series is entirely italicized, as a reminder of McKay’s knotty relationship with Hebrew, excerpted in part:

In Hebrew I’m more than a signal fire in this ocean of grief. In Hebrew the gun runners follow my orders. In Hebrew the wind comes straight from the desert, strong enough to disassemble God’s snores in Hebrew the words for “cherry” and “clitoris’’ sound pleasingly similar in Hebrew I’m the proper kind of beautiful……

The last piece in this section, the second to last in the book, is Number 21. Ceasefire quoted in full:

Blood has its own syntax. Let me send you a draft of this tissue-thin grip we have on breathing. Say what you came to say quick before the helicopters wake up and remind the rockets where to drop, before trouble presses new shapes into your sleeping brain and waits for you to fling your eyes apart in panic.

And then there is a poetic epilogue , in part below:

I miss the boy who made my coffee and that particularly dusty stretch of a Jaffa street where, with an ocean of breath, an armful of concrete went sliding through the plastic sleeve, a six-story drop into a dumpster filled with oblivion.

The last word is super-charged with location and locutions and definitions of life, death and destruction, entwined with the necessity of attention, and the inescapable question of why that building was demolished. A Meteorologist in the Promised Land is bravely original, without pretense It is an exceptionally strong first book.