“People were gathered in the entryway looking at something, and when we stepped forward we saw what: a couple laying on the floor, kissing and embracing in slow motion.”

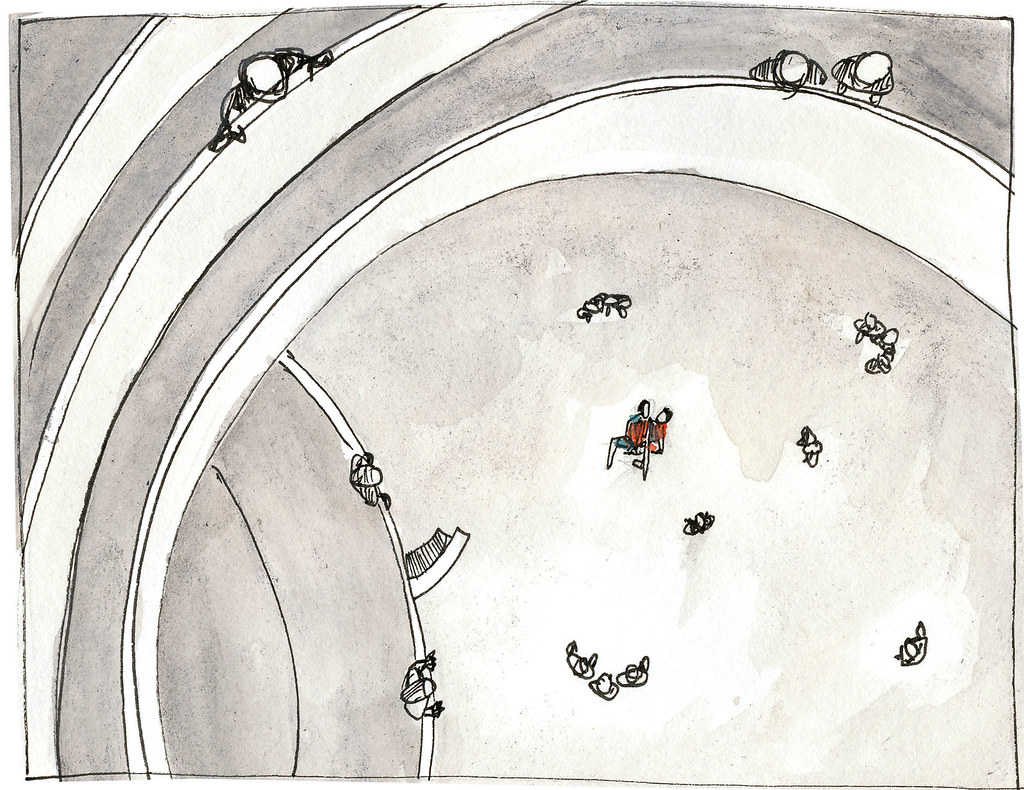

Tino Sehgal, a London-born artist now working in Berlin, creates work that is tempting to call performance art. But Sehgal doesn’t perform; he organizes situations. Instead of working with objects, he uses people, their voices, their bodies, their movements, and their interactions with each other to create social experiences set in museums. Born in 1976, Sehgal is the youngest artist to have a solo exhibit in the Guggenheim rotunda. For “This Progress,” Sehgal trained dozens of “interpreters” to interact with the museumgoers.

Rachel Riederer and Julie Limbaugh teach University Writing to freshmen at Columbia University. In February, they took a group of their students to the Guggenheim to see Sehgal’s “This Progress” and “Kiss.” The students weren’t told anything about the exhibition before the trip to the museum.

_____

RR: When we first walked in, it was striking to see the museum’s walls completely blank.

JL: Tino Sehgal’s exhibit was the first time that all art objects were removed from the Guggenheim rotunda.

RR: People were gathered in the entryway looking at something, and when we stepped forward we saw what: a couple laying on the floor, kissing and embracing in slow motion. There was much straddling and arching of backs. Almost immediately, two of my students (who I hadn’t even realized were a couple) started making out.

JL: Watching an art exhibit erotically kiss while standing next to kissing eighteen-year-olds made me want to move on quickly, but then came the best part: the “Kiss” couple got off “work.” A new couple replaced them, but first they lay down beside the original couple and separately performed the same movements in tandem for roughly ten minutes. What we didn’t know at the time was that the routine was a pastiche of poses from famous kisses such as Rodin’s statue “The Kiss” and Jeff Koons’s series of sculptures “Made in Heaven.” This awkward parallel—of Rachel’s kissing students and the “Kiss” couple—actually helped me enjoy the exhibit more. The orchestration made me think about how what we might consider a spontaneous experience is just a choreographed dance, one that has been happening forever.

RR: We had brought our students to the museum not just because we like to put them into uncomfortable situations, but because we had recently read and discussed a section of Walker Percy’s book The Loss of the Creature. His main idea is that most of us have surrendered our sovereignty, our ability to see the world through our own eyes; we approach things and experiences with so many expectations that we never just see things for what they are. It’s impossible to go to the Grand Canyon and truly see it, because you’re really just comparing it to the 1000 Grand Canyon post cards and the photo on the cover of your Southwest Adventure guidebook.

JL: We assumed our students, coming straight out of high school and years of field trips, found museums quietly boring, stuffy places. Percy writes about ways to “recover” the sovereign experience by going “off the beaten path,” like going to the Grand Canyon alone at dusk, or by taking the cheesiest tour you can find, but paying attention to the packaging of the experience.

RR: That’s what we were trying to do for our students—bring them to this unconventional exhibit with no prior knowledge about what would be there. Just as we were about to leave “Kiss” and head up to “This Progress,” a toddler waddled over to the kissing couple, staring at them really intently. He circled them, checked them out from every angle, and then lay down next to them and starts slowly rolling around, imitating them. It was a perfect embodiment of Percy’s “sovereign experience.”

JL: We had grand expectations of this Teachable Moment in which, as their benevolent teachers, we would supposedly give our students back their museum sovereignty.

RR: That’s what is so compelling about Percy’s whole idea if you buy into the notion that packaging takes away sovereignty. The students had read Percy, and were walking in knowing that they were supposed to be surprised in some way by art that has been selected for them by their writing teachers. It’s like that moment in the essay where Percy poses this question about a student reading a sonnet in English class: Twenty years down the line, will the kid remember the words of the sonnet, or the smell of the textbook, or the smell of the English teacher? It becomes such a rabbit-hole. Were our students going to approach “Progress” on its own terms, or was the whole thing going to be swallowed up in their first time seeing the Guggenheim, which is such a striking piece of architecture, or be subsumed by the fact that their classmates were making out? Anyway, my kissing students disappeared, and by the time our little group started up the ramp, I was already engulfed in pedagogical anxiety.

JL: We walked up “This Progress” separately, each in a group with a couple of students. At the start of the Guggenheim’s spiraling ramp-ways, my group was greeted by an ebullient lisping five-year-old boy who immediately asked us “What is Progress?” He followed up with a hundred “Why’s?” as five-year-olds do.

RR: It was so interesting to see people’s reactions to the children. If the first approachers were adults, I bet we all would have averted our eyes and stepped away, the way New York conditions us to when approached by a stranger. But if a child grabs your hand, you don’t have a choice—you’re in.

JL: Even though I had an inkling of what the exhibit was about, when the adorable kid became persistent with his questions, I felt defensive. Suddenly I had to perform in front of my students; it was unnerving. When the child handed us off to the next interpreter, a teenager, my condition only grew worse. The teen rambled nonsensically, pausing just long enough for us to try and respond, only to interrupt with why everything we had just said was false. Sullen, with my eyes glued to my shoes, I became my students when they come to class hungover or without their homework. Maybe it was the teacher-on-a-field-trip hat that I was wearing, but I wanted to be the one asking questions, socratically deflecting to my students. When we arrived at the top of the spiral, we joined Rachel’s group and I grumbled about the teenager.

RR: Were the children coached to ask questions? The teens coached to be challenging? One of my students, when the child asked her to define progress, said that to her progress meant “moving forward.” The child reported this answer when she handed us off to the teen interpreter, who immediately launched into a lecture on the Western-ness of our idea of progress as a forward motion, explaining that we think of if that way because of our language, and that in Eastern cultures progress is thought of as vertical. That’s actually really interesting to think about, but the information was delivered with a level of condescension and accusation that only a 16-year-old can truly muster. Ultimately I stopped caring how exactly the interpreters had had been coached–either way, all the reactions seemed age appropriate.

JL: Several weeks later, we returned without our students. As our first young presenter trudged beside us, dragging her cute snow boots, as angsty as a seven-year-old can be, she seemed completely sick of “This Progress.” She asked us what we thought progress was (what all the children start the exhibit asking). I felt sorry for the shy girl; I would have hated being an interpreter in the exhibit, especially as a kid. I asked her how long she had been doing this and she sighed a gigantic sigh and said in this pitiful voice, as if she was Sisyphus pushing the boulder up the Guggenheim, “I don’t even know anymore.”

RR: This is how “This Progress” is so different from other works of art. This passage from the Guggenheim pamphlet really stood out to me. It said that even though it’s very different from the art objects we’re used to seeing in museums, the piece “fulfills all the parameters of a traditional artwork with the exception of inanimate materiality. They are presented continuously during the operating hours of the museum, they can be bought and sold, and by virtue of being repeatable, they can persist over time.” Continuity, saleability and repeatability aren’t the first set of parameters for artwork that come to my mind, but that does make sense. And while “This Progress” is technically repeatable, in that Sehgal can train other armies of interpreters to do this exhibition at other museums on other days, but because it’s a social interaction, each iteration is going to be unique.

JL: That’s true. On our second visit—when we went without our students—I arrived certain that I would be in control of the exhibit this time; but instead the exhibit, yet again, proved unpredictable. On my first visit, we had discussed electric cars, buildings in Dubai and the iPad, where on the second visit we talked about umbrellas, Sky Mall, and pearls. It was a Name Your Own Adventure book come to life, and I do love those books.

RR: Yes! We were actually influencing the art itself. We both can look at the same Kandinsky painting and have totally different reactions to it, but then we know that the source of the difference can’t be the artwork itself, but the way that each of us translated and absorbed the painting, or differences in how we approach the piece. Or if the teen interpreter was really charming or an older interpreter had a speech pattern just like my favorite aunt.

JL: Not only is “This Progress” subjective and unrepeatable, it also requires you to take a totally different posture in relation to the art. You can’t just look at “Progress,” you have to do it. I had assumed that my students would be clinging to some pre-formulated expectation that museums are boring and art is hard to interpret, but I realized that I had been operating under the influence of my own expectations about museums. I have spent the last twenty years hoping to find myself in the scene from the movie Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, at the Art Institute of Chicago, or any museum for that matter, with Ferris and his friends Cameron and Sloan. As we pass a row of Kandinskys and Picassos, The Dream Academy plays their cover of “Please, Please, Please, Let Me Get What I Want.” When the song hits its crescendo, we pause in front of Seurat’s “Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte” and stare silently at the Parisians enjoying a day at the park. We lean closer and see just a girl and her mother. We lean closer and see just the girl, her face. As we lean even closer, and the girl’s face turns to dots, we see that nothing’s there. While Cameron surmises that this is how people feel about him when they look closer, I come away, understanding the world, a world of simple, unaggressive dots that when put together make something beautiful. “This Progress” would not be invited to my fantasy.

RR: Experiencing “This Progress” in that same kind of passive mode just isn’t an option.

JL: It puts a lot of pressure on the museumgoer.

RR: Yes. There can be this pressure to analyze and comment on art in a very intellectual way. Whenever I visit a museum in a group I’m reminded of that scene in Martin Amis’s The Rachel Papers where the narrator makes a date to meet a young woman at an exhibit of Blake paintings, and he goes to the museum alone the day before to memorize impressive things to say about each piece. There’s pressure to have an intellectual and critical response instead of the quasi-mystical Ferris Bueller experience. Then Sehgal takes it to the next level: the art itself actually asks you intellectual questions.

JL: And in many ways those questions become mirrors. If you, as the viewer, transform the art, who are you? Why is your influence on the art what it is?

RR: It’s also interesting because you don’t need any visual-art or art-history vocabulary to analyze “This Progress.” Because of the helix shape of the museum, progress happens without any real intention on our part: once you’ve entered the museum, the piece itself moves you along, and 10 or 20 or 30 minutes later, you’ve moved from kindergartner to grandmother, and up eight stories, and all you did was chat and walk forward.

JL: Sehgal created “This Progress” specifically for the Guggenheim. I feel that walking upward gives “This Progress” an optimistic feel, but I wonder how a museumgoer might feel differently about progress if we started from the top and ended at the bottom. Or if “This Progress” is eventually sold to another museum where we simply walk around a gallery space or go up and down escalators.

RR: It really is site-specific; there aren’t many places where forward and upward motion are combined like that.

JL: As we were walking up the Guggenheim’s spirals, we noticed many people taking photos of “Kiss,” which Sehgal has strictly prohibited. On the last stretch of our walk, I commented on the camera flashes to our last guide, a woman probably in her sixties who walked slowly and deliberately. I asked her why this was going on—where were the security guards?

RR: And then she did this great conversational move, very wise-man-atop-the-mountain, where instead of answering your question about photographs, she said, “Well isn’t that just the way the world is? You don’t always have control.” (Actually, think how irritated we would have been if the teenager had said that to us.)

JL: She used a Yoda-meets-Confucius voice, and it was awesome. She started talking about the lack of control in the world, and how in China there is this cottage-industry capitalism springing up where people cultivate pearls in their backyards and the government can’t—or doesn’t—stop them. It turns out that our interpreter had curated an incredible exhibit on pearls that had traveled around the world.

RR: I think this shift in the exhibit’s tempo really does mimic an attitude and pacing of change that happens in life. It’s not just that the older people get to slow down (if they want to hang out with you at the top of the museum for 20 minutes telling you about the different ways that pearls are made and describing the medical research that is going to turn oysters into heart-valve-producing-machines, then so be it!) – it’s also that the content of the conversations was different for the different age-groups too: the inquisitive children, the challenging teens, the ideas-exchange with the adults, and then the older people delivering anecdotes and pearls of wisdom from their lives. That’s a kind of intellectual progress.

JL: After my first visit, I had decided the exhibit was just a gimmick, but after the pearl lady left us, I realized that I had really enjoyed this visit. Our teenager had still said annoying things (he hated his mandatory college writing class—wrong audience!) but my outlook had changed. It didn’t really matter what we talked about or if we clicked with our presenter, bur rather that we were allowing each other to be a part of the art.

RR: Plus, at the end of our walk up to the top of the museum, as we were standing there in awe of the pearl woman and looking down at “Kiss,” the greatest thing happened. A couple in their 60s or 70s lay down on the floor next to the “Kiss” couple and started mimicking the performance, kissing and rolling around slowly. It didn’t take long for everyone at the museum to congregate at the railing to watch. After a few minutes they got up, and everyone started clapping.

***

RUMPUS ORIGINAL ART BY WENDY MACNAUGHTON.

5 responses

Loved this conversation, ladies!

what a cool review! and beautiful art!

totally enjoyable read. you guys rule.

Wow…quit your jobs and become art reviewers!!!

Nice work!Maybe even more interesting than the art work!!

Thanks for the brain tickler! I enjoyed the teacher-as-teacher vs teacher-as-experiencer perspective. Can you please work on air-lifting the Gug to Chicago so we can experience the show as well?

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment, or log in if you’re already a paid subscriber.