In 1997, 21-year-old Lisl Auman took a ride with some friends in a car known as the Thunder Chicken, driven by a man she’d met only that morning. By the end of their journey, that man, Matthaeus Jaehnig, a skinhead high on crystal meth, had killed a police officer and himself. Though she was handcuffed and in the police car at the time of their deaths, Auman was convicted of felony murder and sentenced to life in prison. But a letter to Hunter S. Thompson would change her fate. Matthew Moseley’s book, Dear Dr. Thompson: Felony Murder, Hunter S. Thompson and the Last Gonzo Campaign, tells Auman’s story, and the story of how Thompson helped her achieve justice.

***

The Rumpus: First, congratulations on this book! It’s a great read—fascinating and ultimately very troubling—and an important story for every American to be aware of. How did Hunter S. Thompson first hear of Lisl Auman?

Matthew Moseley: Well, he received a letter from Lisl. It was a very short letter. His books were not available at the prison library. He received tons of mail. What made this one different is that she was selfless in her letter. And that really captivated him. She didn’t really ask him for anything. She just said, hey your books are banned. In case you were wondering who I am, you know, I was wrongly convicted of a crime I didn’t commit, that kind of thing.

Rumpus: How long had she been in prison at that point?

Moseley: The crime happened in 1997, and she wrote the letter in 2001, so it had been about three years. She had read the book in the Denver County Jail while she was awaiting trial, and then she got transferred to the women’s correctional facility. And it was three years later that she was still thinking about this book. And she was like, you know, I think I’m going to write this guy a letter. And so she did. And the title comes from her action. But it also inspired me to write a memo to Hunter. And that’s what “Dear Dr. Thompson” is about; it’s not just Lisl’s letter, but it’s also my memo–both of which kind of changed the course of history. It’s a theme that I really wanted to draw out in the book—besides that we have to abolish this silly Felony Murder rule—is for everybody to write their own letter. That’s what Hunter would have really wanted for people to understand, how one little letter can change your life. If you reach out, if you connect to the right person in the right way, it can change things, or get you out of prison.

Rumpus: Tell us about the Felony Murder law. I know it’s a complicated law, but maybe in the context of Lisl’s case, what is the felony murder law, and what does it mean?

Moseley: Felony murder allows a person to be convicted of a crime that they had no intent to commit and no desire to happen. It is a relic of 18th Century English law that basically makes participants to a crime punishable. Like if you’re Bonnie and Clyde, and you’re Bonnie, and you’re driving the getaway car, and Clyde robs and kills the banker, Bonnie’s held just as liable as Clyde is. Now, every other country has pretty much abolished this law. And we are one of the few remaining countries that still has it. What it does is it allows prosecutors to cast a very, very wide net around any crime so that anybody with any even peripheral connection, if they don’t sell out somebody or make the right deal or whatever, they could be liable too.

Rumpus: What’s interesting about Lisl’s case, too, is that there were several other people driving with them, but those people weren’t prosecuted.

Moseley: They did a very good job of keeping those people in the background. And what they did was they cut a deal with them. They said, “If you testify against Lisl, we’ll let you walk out.” And remember these are skinheads already, who had already exhibited tremendous capacity for violence, and they let them out of jail. And Lisl, who—my god, she was the furthest thing from a skinhead you could imagine—because of all the context of skinhead violence in Denver at the time, they held her up as the symbol for all the skinhead violence that had happened, and they kept everybody else very quietly in the background.

Rumpus: And there was this misperception that Lisl and Mattheus were boyfriend and girlfriend, that she was deeply associated with him—like Bonnie and Clyde—right? But hadn’t she just met him that day?

Moseley: That’s the story that the prosecutors told. That’s the story that Bill Ritter—who is now the governor of Colorado—and Tim Twining told to get people to make the connection with her to Jaehnig and to this violence.

Rumpus: In your book, you quote Thompson writing that “What happened to Lisl Auman can happen to Anybody in America, and when it does, you will sure as hell need friends.” And you point out the tragic irony that, in Lisl’s case, justice was served because Thompson intervened. What does this case really say about “justice” in America?

Moseley: Well, when Lisl’s plea deal was announced, a lot of people were like, “Isn’t this awesome! Isn’t this great!” And “Congratulations!” And “Hunter did it!” And you know I had this sort of sad feeling that, yeah, he did do it; but why was he necessary? And what about everybody in America that’s wrongly convicted, shouldn’t they also have their day in court? You shouldn’t need a Hunter Thompson in our system. You shouldn’t need somebody like me or having to organize a campaign or Warren Zevon playing “Lawyers, Guns and Money.” That’s wrong. That’s partly why I wanted to tell the story.

Rumpus: It’s fascinating, too, because it wasn’t just that Lisl had Hunter; it was that Hunter had, as you wrote, “a far reaching and powerful web of people who were at the very top of their professions in music, law, art, politics, theater and sports.” That’s incredible influence—not even just one man’s influence, but a whole army of influence. Who were some of the people on the Free Lisl team?

Moseley: Hal Haddon, a very well known criminal defense attorney, pointed out that if it would have been just Hunter by himself, he could have been dismissed as the ravings of a madman. Because he in some way, in his post-Gonzo era, kind of recognized his impact on the story, planned for it, and then got—in the communications profession we call them third-party validators, people who are carrying the message for you. You know, it’s not Matt Moseley, it’s not Hunter Thompson, it’s not even Lisl Auman. It’s Johnny Depp. It’s Morris Dees, you know, the Head of the Southern Poverty Law Center who bankrupted the Klu Klux Klan. Gerry Goldstein the former head of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. There were a lot of people. You can see, in the back of the book, some of the people: John Cusack, Benicio Del Toro, Bonnie Raitt. A lot of people who felt that, even on first glance—and that’s what got me involved—that it was obvious that she was innocent. I read this one story, and it was obvious that she didn’t kill the cop; she was in the police car. And she didn’t know the guy who did.

Rumpus: That touches on the huge role of journalism in this case. You read the story and the influence here became very public. What role, for better or worse, do you feel journalism played?

Moseley: This is why as a communications strategist this story really fascinated me. Right from the beginning the prosecutors were able to very adeptly control and frame the story right from the crime scene. You know, “We believe that she was his girlfriend. She may have handed him the gun. She was uncooperative.” None of that was true, but they were setting the stage for a story line to develop. And they told that story expertly well. There was no counter-defense because you know the defense attorneys are always like, “If you say anything it can be used against you in court.” Well, what we did, and what Hunter was so powerful at recognizing was how to change the narrative. From the rally, once we had Warren Zevon come out and play “Lawyers, Guns & Money,” and Doug Brinkley stand up, and the former First Lady of Colorado say it was a women’s rights issue at work—that totally changed the narrative and a new story line developed. Which I found fascinating, because that’s kind of what I do for a living. It was just fascinating to kind of watch it. It was big, too. Once it hit, we were on every paper, all over the place.

Rumpus: The defense, what did they have to prove in front of the judges to get Lisl’s case overturned? It seemed that there was this key question of whether or not she was guilty of the burglary in the first place, or whether or not the first jury had been instructed properly. What do you think were the most important factors that they had to prove to get her case overturned?

Moseley: They had to prove that it wasn’t Lisl running from the police. The defense—her appeals attorney—had to prove that it was in fact Mattheus Jaehnig who was in fact “in flight” from the burglary, for his own reasons that were independent of Lisl.

Rumpus: And that neither of them ultimately had committed the burglary.

Moseley: No! Right! Exactly! It was the other three people whose car went free. They went riding away, taking a joy ride into the mountains!

Rumpus: What obstacles did you encounter when you were researching this book. Who helped, who stood in your way? What was it like?

Moseley: I got all my research from the records basement of the city and county building in Denver. The prosecution, police, Bill Ritter—they prosecuted Lisl over a course of five years, three levels of the judiciary all the way to the Supreme Court. They publicly flogged her and flogged Hunter and everyone who stood up for her. And in the end, when they overturned the decision, not a single one of them would talk to me. Not a single one of them would stand up and say, you know, we still think we were right. And they would not give me the evidence—or rather, they made an offer, but as I explain at the end of the book, it was $150 a box, a redaction fee, a fee for another lawyer to sit with me while we go through the records. It would have been thousands and thousands—I mean like $50,000.

Rumpus: And they were public records, weren’t they?

Moseley: They were public records. But there were files in there that they don’t want people to see. There was a meeting held, that they held with the police officers right before they changed their statements. And the police officers walked out of that meeting, they walked over to the police station, and they both changed their statements to say they had seen her hand him the gun.

Rumpus: When she was already cuffed and in the car, at that point?

Moseley: Well, that was right before that. And remember this: there were no fingerprints found on the gun. There was no gun residue found on Lisl. There was just no proof.

Rumpus: It sounded like from what you wrote that the officers intimated that they saw her hand him the gun, that they saw her halfway behind a wall lean down… And the prosecution lead the jury to believe that the gesture behind the wall was her handing him the gun. When really it was so fuzzy. To put someone away for life on such fuzzy evidence seems itself criminal.

Moseley: Remember, the jury even said that they knew the cops were lying. But it didn’t even matter to them in the decision, because they felt like she was guilty of something, so she had to pay for something.

Rumpus: Another thing that was really interesting: The cop who was shot—Officer Vanderjagt—his wife Anna eventually spoke out with forgiveness for Lisl for her involvement in this case. And that proved pivotal?

Moseley: That’s correct. See, it was very difficult for them to reconstruct the same case that they had had before, because they couldn’t tell the same story any more, because it just wouldn’t hold up. It was untrue. Everybody knew that. They couldn’t say that she handed him the gun. They couldn’t say that she was his girlfriend. Because it was all lies.

Rumpus: And it had been exposed by then.

Moseley: So, they knew they would have a difficult time. I think, though, Anna Vanderjagt—there was her supreme court argument that kind of said, “You know, it’s difficult to keep reliving this, and I’m honestly not sure what the right thing is here.” She was expressing some softening. And when the deal came, she wrote a letter that said, you know, if Lisl accepts responsibility, then I’ll do this… And that was hard for Lisl. It meant that she had to plead guilty to a crime that she didn’t really do. But at that point there’s really only one thing to do and that’s to cut the deal and run.

Rumpus: You were the public relations manager for the “Free Lisl” campaign and later for Hunter S. Thompson’s funeral. Through you work and your dedication to this case, you became close friends with him. How was the Hunter S. Thompson that you knew different than the legend?

Moseley: My role in this was I felt like I had something to offer, and I wanted to be professional about it. And I had a deep respect for him. He was a big hero of my life in some ways. I mean, he was just another principle in the case, and we had a job to do. So whenever I was around him I always tried to maintain that kind of professional thing. But you know we did, in the end, develop a very close friendship. He was a gentleman. I think all of the—you know, it was not as bad as you’d think and it was crazier than you would have thought. If that makes any sense. [Laughs]

Rumpus: So did you guys have some adventures?

Moseley: Yeah, we had some great adventures together. I think at the end of his life, it got a little difficult. You know, I wasn’t privy to his inside stuff. We didn’t talk about that. We talked politics and, you know, state house polling numbers and kind of stuff like that.

Rumpus: But did you blow shit up?

Moseley: [Laughs] We blew some shit up. We blew up a bomb. Just, you know, with Anita [Hunter’s wife]. It was a propane canister wrapped in nitroglycerine that we bought off a gag. I had the shotgun and we blew it up. I tell you though one of the things about the funeral: that was the craziest night of my entire life. I equate it to working the Democratic National Conventional by yourself. There were 300 media people in town all wanting to get in. And Johnny Depp was like, look, it’s a private funeral; there’s no media here. But Doug Brinkley [historian and Thompson’s literary executor] and I convinced Johnny to let Kit [Katharine Q.] Seeley from the New York Times come in. And he was calling me, like, “Who the hell do you think you are? You’re not going to let the Times in.” I had the [Times] editor calling me and saying, “C’mon, we gotta get into this event.” And I was like, listen, the Times wasn’t allowed into Hemingway’s funeral either, so back off. We ended up cutting a deal where she could come in with no notebook, no recorder, and she had to leave after the ceremony. What I really tried to do was to frame Hunter in a way beyond the drugs and the guns, and that he truly changed the face of journalism. He invented a new style of Gonzo journalism, where the journalists were participants in the story. And that paved the way for so many others after him, like Tom Wolfe and David Halberstam and people who went on to write great things. Hunter was at the very beginning of that movement, and that’s what I wanted to circle back with on his legacy.

Rumpus: That’s a great place to circle back to. My last question is: Do we know how Lisl is doing today? Do you know where she’s at or how she’s doing?

Moseley: You know, she has moved on with her life very admirably and has picked up the pieces. What’s great about her is that she had something to prove to everybody that helped her get out. And she came out very strong from prison, and not broken or weak. She said she had a second chance at life and she wanted to make it the best it could be. And so, she’s got a great job, and she’s in a stable relationship, and she’s just moved on. She’s probably just like us—just kind of a normal girl who got caught up with bad timing, bad guys, wrong night, wrong day. And it just kind of went real south real fast. And you know it’s just a lesson to those of us who have kids, too. I’ve talked to a lot of moms who read this book, who just, like, shudder at the though of their kids climbing in a car with somebody sometimes. You know, like we’ve all done. You’re out sometime, you’re nineteen, and “Hey I need a ride home.” And somebody does something and…

Rumpus: Oh it’s true. My 11-year-old son just started hanging out with some kid who’s been shoplifting. And he told me. And I’m like, dude! You and Lisl!

Moseley: No way! You’re like: read this book!

Rumpus: Yes! I really told him about it. I said, you know, if you’re friend is shoplifting and you’re with him, don’t think they’re not going to shake you down, too.

Moseley: Exactly.

Rumpus: It was good timing. Very good lesson-learning.

Moseley: [Laughs]

Rumpus: So, you’ll be reading in San Francisco this weekend, right?

Moseley: That’s right.

Rumpus: And then you’ll be back to read at the Monthly Rumpus on July 12, yes?

Moseley: I’m planning on it!

Rumpus: Really looking forward to it.

9 responses

This is an amazing and important interview.

Aw! Thanks boss.

This was totally fascinating. Well Done!

SHUDDER not SHUTTER

Well done, Julie. Really important interview. On a lighter note, my favorite question: But did you blow shit up?

Love the interview! Can’t wait to read the book!

Great interview. It’s strange… I’d never heard of this site until a few days ago, and now I’ve followed four or five random links here. Must be fate.

Really Great interview!

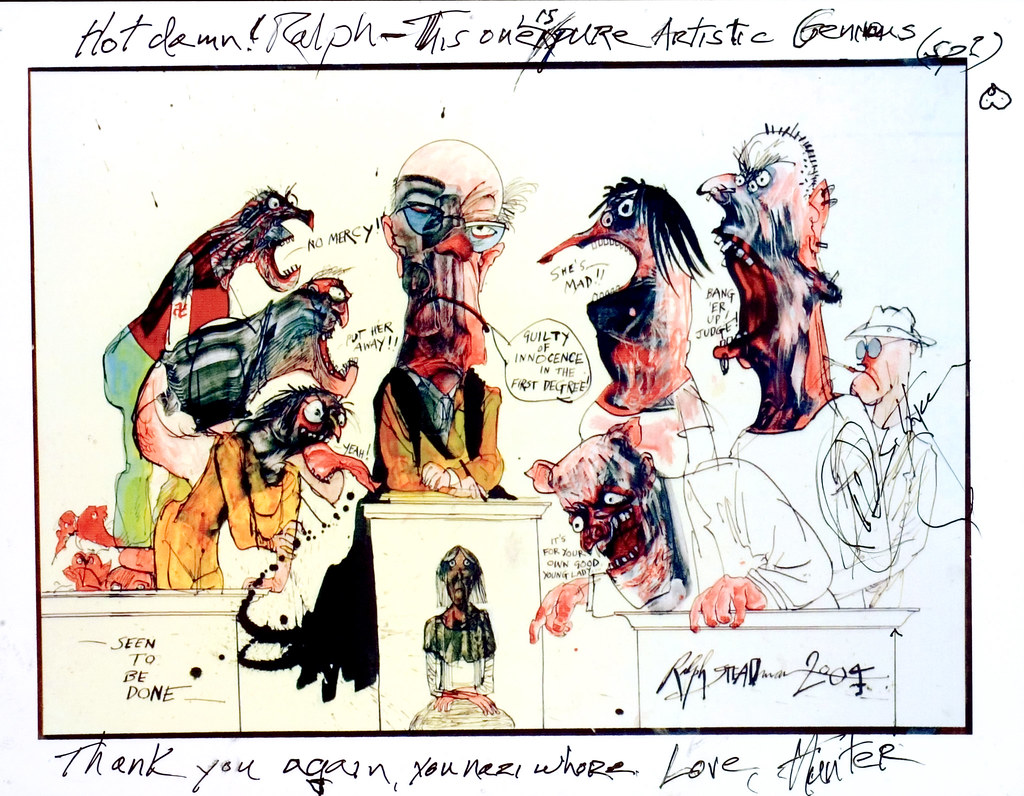

I love this they say a picture is worth a thousand words in this case this picture is worth an entire interview lol

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment, or log in if you’re already a paid subscriber.