Grotesquery is the nature of the humor in The Black Automaton.… [Douglas] Kearney leads the reader through laughter at the unchangeable rottenness of life, rather than throwing a tearful pity party.

Grotesquery is the nature of the humor in The Black Automaton.… [Douglas] Kearney leads the reader through laughter at the unchangeable rottenness of life, rather than throwing a tearful pity party.

“Finally, like a boxer [who] has just broken an opponent’s face, I thank God.” So ends Douglas Kearney’s acknowledgments page to The Black Automaton. It’s a perfect final jab (allow me the pun) in a book filled with satire, despair, and jokes made all the more clever as the reader realizes that this shit isn’t funny. Or is it?

Take for instance the poem “Swimchant for nigger mer-folk (an aquaboogie set in lapis).” I could fill this entire thousand-or-so word review just by discussing this one poem. The mer-folk of the title are the slaves kicked overboard during passage from Africa to the Americas, yet this is never spelled out explicitly or clumsily for the reader. Similar to the mythology of the Detroit techno music pioneers Drexciya, Kearney imagines the drowned prisoners evolving (mutating? adapting?) into aquatic humans. To add insult to injustice, Kearney adds song lyrics from the “Jamaican” Sebastian Crab character from Disney’s Little Mermaid: “jus look at de worl around you right ere on the ocean floor such wonduhful tings surroun you what more is you lookin for?”

The poem begins, “never learned to swim/ but me sho can d i v e” as the letters of the final word cascade down the page into lines that criss-cross and spill right across the binding. Kearney juggles Sebastian’s ditty with a bit of Eliot, and of course the nod to Parliament’s “Aquaboogie.” It’s difficult to tell where the poem ends, but that’s the nature of Kearney’s musical style. Like communal songs, these poems don’t always conclude so much as stop. Towards the bottom of one page, we have the grotesque joke, “ATTENTION: NIGGER MERMAIDS… DO NOT BLEED IN THE SEA. THE STAINS WON’T WASH OUT… MUCH OBILGED, THEE MANAGEMENT.”

Grotesquery is the nature of the humor here. It’s not even so much comedy as it is gallows humor, the laughter of relief. It sure as hell isn’t “light verse.” Kearney leads the reader through laughter at the unchangeable rottenness of life, rather than throwing a tearful pity party.

Drawing inspiration from trails blazed by Amiri Baraka, Allen Ginsberg, Langston Hughes, D. A. Powell, George Clinton, Stephane Mallarme, and Public Enemy, Kearney uses the space of his pages, creating flowcharts and linguistic diagrams while bouncing between several dialects, from traditional Euro-poetic lyric to Beats and hip-hop. Kearney also designed and illustrated this book, essentially creating a complete artistic package from cover to cover. He raises the bar of what a poetry book can be. He is, without doubt, my new hero.

Speaking of heroes, the whole book feels like an avant garde comic book, albeit one in which the words create most (but not all) of the imagery. Unlike Toby Barlow’s recent “epic” werewolf “poem” Sharp Teeth, which was touted as a graphic novel without pictures but was really an urban monster novel with line breaks, The Black Automaton is actually good poetry that feels like visual art. It frequently is visual art, in fact. The cover image is that of a giant knocking down skyscrapers in a fiery rampage (think a sci-fi metaphor for race riots). This appears to be the black automaton of the title, although the latter is also the robotic black lion of the cartoon television series Voltron. John Henry as well drops in to Clang! his own blazed trail, linking traditional American folk heroes to the new mythology that Kearney tears out of pop culture. “The City vs. John Henry” puts the hero at odds with his most fearsome foe yet, with only his hammer and metrocard to aid him. From “Part 6: Obituary”:

no one doubts your heart John

the busted meat of it the machine

carve the right angles of your grave

raise high its robot arms

and later:

giving America a charlie horse

CLANG! CLANG! CLANG! CLANG! let them drop on down…”

The CLANG!’s appear to overlap on the page.

Many of these poems are, like “Swimchant,” visually awesome. Some, most notably “Floodsong 1: Canal Rats’ Chantey,” are literally written in 3D. Words appear on top (not above but on top) of other words, stacking in a way that is not quite illegible but certainly challenging. Whereas other poets are content to make obscure references and inside jokes, Kearney is more direct in content yet often cryptic in presentation. Deciphering The Black Automaton is one of the joys of the book.

Many of these poems are, like “Swimchant,” visually awesome. Some, most notably “Floodsong 1: Canal Rats’ Chantey,” are literally written in 3D. Words appear on top (not above but on top) of other words, stacking in a way that is not quite illegible but certainly challenging. Whereas other poets are content to make obscure references and inside jokes, Kearney is more direct in content yet often cryptic in presentation. Deciphering The Black Automaton is one of the joys of the book.

Other Floodsongs, all singing the threnody of New Orleans, look more traditional on the page, from the “Mosquitoes’ drinking ditty” to the “Water moccasin’s spiritual.” My favorite is “Floodsong 5: Bullfrog’s liturgy of the Eucharist.” Kearney’s frog sings of consecration by “my heart of trembling mud,/ my blood of falling sand/… my bones of melting song,/ my tongue of humming ghosts,/ my throat of burning eggs…”

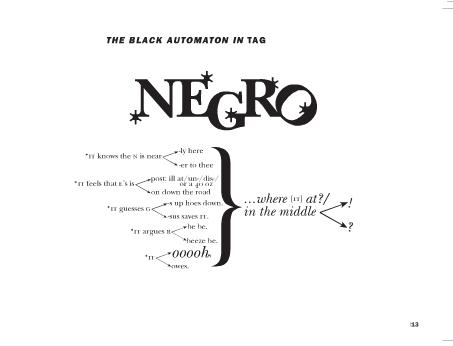

The titular character stars in several episodic poems sporadic throughout the book. The whole adventure begins with “The Black Automaton in tag,” one of three tag poems that each deconstruct the spelling and meaning of a single word. Since we began this review at the end of the book, we might as well finish with the first poem.

The word NEGRO appears in a huge font, each letter bedazzled by an asterisk. Below is a sort of flowchart as each letter is divided into two options, all of which are overshadowed by a single bracket as they pertain to the lines, “…where [IT] at? / in the middle.” Arrows point from the word “middle” to the alternatives of an exclamation point and a question mark.

The word NEGRO appears in a huge font, each letter bedazzled by an asterisk. Below is a sort of flowchart as each letter is divided into two options, all of which are overshadowed by a single bracket as they pertain to the lines, “…where [IT] at? / in the middle.” Arrows point from the word “middle” to the alternatives of an exclamation point and a question mark.

Sounds confusing? Sometimes it is. But so is history. So are race, class, and politics. Kearney manages to punch the reader in the brain, employ math and illustration in verse, pull the rug out from under the poetry of witness and social justice, and create a book that is the exact polar opposite of crap. This is a badass book.