If you took the love child of Dylan and Patti Smith, conceived under a full moon with Waits howling somewhere out of sight, and raised him to twenty-four in a dark cathedral with only a guitar and drum set and organ at the altar and the pews were a bar where the drinks were plentiful and cheap and beautiful, sad, hard-drinking women congregated to worship songs sure to break anew every broken heart you might have a songwriter like Leo.

If you took the love child of Dylan and Patti Smith, conceived under a full moon with Waits howling somewhere out of sight, and raised him to twenty-four in a dark cathedral with only a guitar and drum set and organ at the altar and the pews were a bar where the drinks were plentiful and cheap and beautiful, sad, hard-drinking women congregated to worship songs sure to break anew every broken heart you might have a songwriter like Leo.

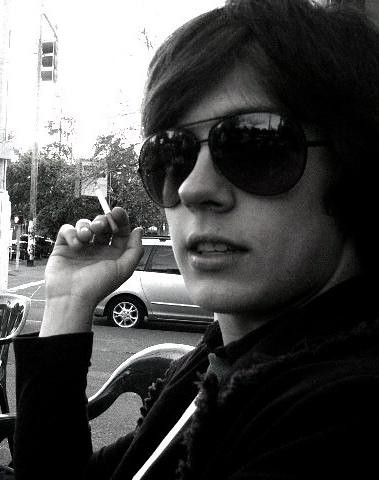

Leo London loves the Beats and the Beatles. Leo London loves booze and cigarettes and guitars of many makes. Leo is baby-faced, flop-haired, perpetually unshaven, all intense raccoon eyes and shuffling steps, all stumbling grace and celebration of being laid low. If you took the love child of Dylan and Patti Smith, conceived under a full moon with Waits howling somewhere out of sight, and raised him to twenty-four in a dark cathedral with only a guitar and drum set and organ at the altar and the pews were a bar where the drinks were plentiful and cheap and beautiful, sad, hard-drinking women congregated to worship songs sure to break anew every broken heart you might have a songwriter like Leo. Leo London, son of drug addicts, today hung-over and full of new sorrow and excuses, tomorrow hung-over and full of bright hope and the possibility of something sung in a cracking, human voice that could encompass all that and then some. Leo, barely twenty-four-years old, sleeping each night in a garage with the guts of the Wurlitzers he spends his time restoring, pieces of instruments made to pieces of music marching rumba staccato décolletage, brass band two-step jukebox tilt-a-whirl, the music of his dreams as terrible and glorious as the music of his days.

You haven’t heard of Leo London. Nobody has heard of Leo London, though the name has a certain ring: surely anyone who chose the name Leo London couldn’t help but know they were claiming to be an artist of international, cosmopolitan significance, that expectations would need to be met. Not Leo. He thought he’d read the name Leo London on an album cover, imagined he was making a reference, being derivative, when in fact he’d invented it wholesale. Accidentally and completely original, the invention of Leo London is very Leo London. If absolute devotion to art is the measure of the artist, Leo London is the artist’s artist. Aesthetically, Leo’s music IS Leo London.

You haven’t heard of Leo London. Nobody has heard of Leo London, though the name has a certain ring: surely anyone who chose the name Leo London couldn’t help but know they were claiming to be an artist of international, cosmopolitan significance, that expectations would need to be met. Not Leo. He thought he’d read the name Leo London on an album cover, imagined he was making a reference, being derivative, when in fact he’d invented it wholesale. Accidentally and completely original, the invention of Leo London is very Leo London. If absolute devotion to art is the measure of the artist, Leo London is the artist’s artist. Aesthetically, Leo’s music IS Leo London.

Leo sometimes writes about being from Oregon. He mentions places I’ve gone and go—Portland, with Gold Hill in the rear-view mirror, Hendrick’s Park, St. Marie’s Church, the payphone at the last Texaco on the last curve of Prairie Road. He asks the questions I want to: how did I get here, and why did I stay, and what happened to the innocence of the boy I was? How long, and how far gone and far ahead is something better—and if I’ve lost what you gave me, and I take what I get, what do I have left? Leo’s idiom is the ash of the cigarette brushed from a guitar and the ashtray laying gray and getting cold, empty cars and boxcars and futures laying like pavement in the sun, cracking beneath the feet of what we’ve done. Growing old is being outside in the snow without a coat. The record is always skipping, and we all love rock and roll, and we all like it here at the bottom longing for something easier and purer and finer.

Yet Leo’s Lane County isn’t my Lane County. His is the school of the bottom while I only choose the bottom. His home is a garage in a house way out West where Eugene gets gritty; his bed is a mattress laid on the cold concrete floor; his grandfather is a deaf auto mechanic and Leo himself occasionally moonlights in auto-repair when he isn’t refurbishing instruments of all kinds to make the cash for another pack of cigarettes. He lives off nachos made with government cheese, doesn’t shop at second-hand stores or even Goodwill because such establishments require cash. He has been known to acquire other people’s scarves, jackets, and boots by complimenting the desired couture in such a way that they recognize just how little he has. He plays gigs at bars in return for free booze, and to master his record, he sold a beloved Gibson sobbing all the way to the pawnshop. It is not that Leo’s poverty makes him a better musician or a better man, just that it is thorough and authentic and informs the grammar of his music: his is not the affected poverty of the hipster, the glorified life-of-the-streets trumpeted by the rapper born middle class. When Leo speaks of the bottom it is because he sleeps on the ground. The cold, empty boxcars are the ones on the tracks by the lumberyard down the street. With him it is always the last cigarette in the last pack of cigarettes and there is never change enough in his pockets for the new pack.

My friend, the guitarist Justin King, introduced me to Leo; he produced Leo’s album, the last record to come out of Blackberry Hill Studio, Justin’s dream which he now has been forced to lay to rest. The studio was beautiful: an eight-faced, octagonal dome atop a hill out the sticks of Lorane highway, the whole valley spread below in patches of forest and clear-cut and field like an erratically-shaved head. Justin and Leo met at a café, where their girlfriends had briefly worked together; having heard Leo’s music, Justin decided to make one last record, but time was short—the hill had to be cleared by late December, and they began in late November, the golden Fall darkening to the cold gray press of Winter. They went to the Hill, and over consecutive nights Leo played through his repertoire and they debated and chose the songs and began to discuss the arrangements, arguing over cups of coffee and cigarettes and in the late evenings bottles of whiskey and unending cases of beer. For a month the sun set day after day on the hill and the nights drew out in sheets of rain and sleet and occasional, sparkling mornings where the air and sky were so cold and clear that only the task ahead made such awful clarity tolerable, and they worked. The two of them played all the instruments, Justin a strong editor with his perfect pitch and mastery of every instrument, and Leo versatile too, so that they battled over who had the best take on a bass or percussion line. They finished just after Christmas, and Leo helped Justin clear the studio of the baby grand, the thirty guitars and dozen basses, the drum set and amps and board, to pack away what was left of the original dream—only empty rooms remained. The record they took with them.

My friend, the guitarist Justin King, introduced me to Leo; he produced Leo’s album, the last record to come out of Blackberry Hill Studio, Justin’s dream which he now has been forced to lay to rest. The studio was beautiful: an eight-faced, octagonal dome atop a hill out the sticks of Lorane highway, the whole valley spread below in patches of forest and clear-cut and field like an erratically-shaved head. Justin and Leo met at a café, where their girlfriends had briefly worked together; having heard Leo’s music, Justin decided to make one last record, but time was short—the hill had to be cleared by late December, and they began in late November, the golden Fall darkening to the cold gray press of Winter. They went to the Hill, and over consecutive nights Leo played through his repertoire and they debated and chose the songs and began to discuss the arrangements, arguing over cups of coffee and cigarettes and in the late evenings bottles of whiskey and unending cases of beer. For a month the sun set day after day on the hill and the nights drew out in sheets of rain and sleet and occasional, sparkling mornings where the air and sky were so cold and clear that only the task ahead made such awful clarity tolerable, and they worked. The two of them played all the instruments, Justin a strong editor with his perfect pitch and mastery of every instrument, and Leo versatile too, so that they battled over who had the best take on a bass or percussion line. They finished just after Christmas, and Leo helped Justin clear the studio of the baby grand, the thirty guitars and dozen basses, the drum set and amps and board, to pack away what was left of the original dream—only empty rooms remained. The record they took with them.

In the last months, I have hung out with Leo and his girlfriend Laurie in occasional dive bars and coffee shops and even my apartment, where we attempted to drink enough Jameson to summon the volume to wake the neighbors (we failed—they sleep hard, or rather, are hard of hearing). I am cerebral and keep my cards so close to my chest even I don’t know what I’m holding, a silent, calm observer who rarely is noticed; Leo is outgoing, open and energetic, speaking usually in loud, strident tone, a cloud of cigarette smoke rising about him like a declaration of necessary sin: this is what I need and want, and if it kills me, so be it.

On his birthday, struggling from beneath a dozen drinks, Leo swung his cigarette through the air in the cool dark of a friend’s patio, conducting Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue, his hands and that perfect music puncturing and weirding the starlit evening as he confessed, slurring and emphatic, that he never expected to make twenty-four, that it was, how do you say, not a blessing at all, not really, not this life lived this way. A mistake not to already have gone up in a shimmer of heat and light, to have said something, man, really said something. I put an arm about his shoulder, comforted him. I would never speak those words, but I feel exactly the same on the edge of thirty: better to have gone truly than to gesture haltingly, to live a life of faint-hearted accommodation. Leo’s integrity lies in his inability to sin enough to sully the purity of his longing: he may speak from the bottom, but in the cigarettes, drugs and rock and roll is an imminence of heaven.

***

Leo London‘s “I Don’t Know”

Leo London’s music is available on CD Baby.