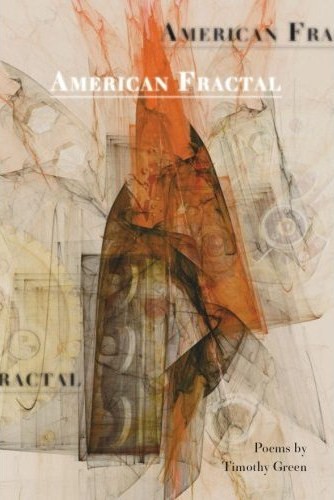

Green’s debut collection American Fractal picks up where scientific discourse leaves off, exhibiting a rare display of confidence in this integral unity, as a metaphor for poetic practice, and as manifest in varying degrees in Nature, each individual, and humankind.

Green’s debut collection American Fractal picks up where scientific discourse leaves off, exhibiting a rare display of confidence in this integral unity, as a metaphor for poetic practice, and as manifest in varying degrees in Nature, each individual, and humankind.

True geometric fractals are a rarity in nature, and represent, contrary to the Latin etymology of the word fractal (fracture), a uniquely uniform structure whose chief characteristic is self-similarity, rather than variance: a snowflake, lightning bolt or cloud can be split into parts approximating a copy of the whole, parts which are identical (or nearly) at all levels of magnification. (Ironically, their structural consistency is what makes them infinitely complex, and thus a subject of fascination for scientists.) Green’s debut collection American Fractal picks up where scientific discourse leaves off, exhibiting a rare display of confidence in this integral unity, as a metaphor for poetic practice, and as manifest in varying degrees in Nature, each individual, and humankind.

The idea of procedural intelligence in Nature may be hard for modern readers to buy, given our inhabitation of a world fraught with atomic instability and natural disasters. The epigraph by Douglas Hofstadter clues us in: “It turns out that an eerie type of chaos can lurk just behind a façade of order—and yet, deep inside the chaos lurks an even eerier type of order.” These pages constitute a fashioning of and an epic search for this “eerier type of order”—pursuing, along the way, logical connections and continuities in the material world, through the analysis of not so much patterns, but forms. Juxtaposed images do this (“My/ mother making sense. One footprint falling/ into the next”) as do singular images: “Two hands/ holding flares guide the idle/ traffic home, while overhead/ in the apple-picker an electrician/ works his quiet length of cord.”

Modern history and other causal systems of analysis may appear to conflict with this perception of order-within-chaos, for most conceptual systems attempt to deconstruct or solve for, rather than admire, structural inconsistencies—but a poet, dwelling as poets do in possibility rather than formulae, is in a unique position to allow for and even celebrate irregularity (as well as to trust, to a degree, the quasi-methodical order-within-chaos of the unconscious mind itself, as relating to surrealism or neo-surrealism, or not).

Double-edged desires amount to complicity with what Elaine Scarry termed “the making and unmaking” of the world, in “The Urge to Break Things”: “It comes on young and fast, first with toy trucks, then with/ lead pencils snapped in half. Pinched flesh, plucked hair./ A little blood dabbed with a napkin. No one notices wounds/ when they heal nightly. Smashed plastic fills the dumpster . . . There’s music in breaking glass.”

Double-edged desires amount to complicity with what Elaine Scarry termed “the making and unmaking” of the world, in “The Urge to Break Things”: “It comes on young and fast, first with toy trucks, then with/ lead pencils snapped in half. Pinched flesh, plucked hair./ A little blood dabbed with a napkin. No one notices wounds/ when they heal nightly. Smashed plastic fills the dumpster . . . There’s music in breaking glass.”

How grave of an epistemological problem is it, really that “The refrigerator hums a perfect/ middle C but offers no intent”? (From “Meditation on the Six Healing Sounds.) This poem and others wrestle with Kant’s “das Ding an sich,” the thing-in-itself, and Green’s lyrical gifts beautifully augment his meditative reflections, not just on entropy and ruin (a cornered market in contemporary poetry if there ever was one) but also the centripetal movement of the poem, and of the human spirit. “The Urge to Break Things” ends with an image not so much of communion with the thing, or a speech act from or to it, but of awe: “An oxymoron/ incarnate: matter that matters: chaos quietly controlled.”

One response

That’s Tim Green. Some readers may want to know his first name w/o having to search further. Red Hen published the book; Green edits Rattle.

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment.