World Enough is, despite the sometimes soft dulled-razor language, an incredibly smart, idea-driven book, and the in-charge idea and/or force seems to be America, viewed both from within the country and elsewhere.

World Enough is, despite the sometimes soft dulled-razor language, an incredibly smart, idea-driven book, and the in-charge idea and/or force seems to be America, viewed both from within the country and elsewhere.

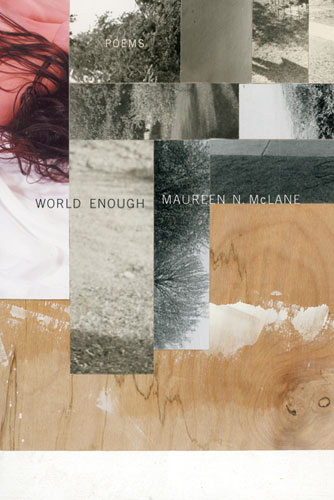

Maureen McLane’s Same Life was one of the most exciting and interesting and gorgeous debut collections of poetry from the aughts, or the 2000s, or whatever the decade is presently tagged as. She wrote lines like “The place I live is only sometimes shareable thus weeping” and wrote compact, perfect gems like “There is a Place”:

There is a place in the world

for cracked things: the wedding

glass, the Zuni jaryou dropped, my poor idea

of god. Hear

how my voice breaksin the highest register?

Same Life is full of poems just like this: gnomic, satisfyingly nonlinear, loaded with nutrients of meaning and mystery, poems which end up offering massive, indirect joy and gorgeousness. Plus smart, whiplashingly (but not stuffily) intellectual: for those of us who like our poems to feel smartly and/or think emotionally, McLane’s Same Life offers the best of the rest of contemporary poetry—the occasional pinwheeling attendant in elliptical work, the elisions and play—plus a massive dollop of plain old smarts.

It wasn’t all hallelujah, however: McLane occasionally suffered a quantum of cuteness that clotheslined her best intentions. Here’s “Stars Arranging…” in which her intellectual sugar gets a bit too candied:

stars arranging themselves

according to old mythsblinking their fame

to the newest fans of the cosmoso you are so fabulous

I could die of it!what am I

if I liebelow the earth

below the skyif burned to rise

to ash the skywould the question be

not how but why

The first half of that poem is workable, good if not great, but it works entirely due to that sudden directness three stanzas in, the address to you, the turned + direct glance. However, before and after that form-rupturing outburst, the poem’s gloppy: the last two stanzas are uncomfortably close to an 11th grader’s deepest verses. Though the language is playful—if one comes to poetry looking for rich sound, full rhyme, this poem offers quite a bit—the play is not, at its core, very generative. The language is, at best, staid, echoey in the worst ways, in that you can see what’s coming [lie/sky/why].

Still, were poetry baseball and Same Life a rookie, it would’ve hit strong, occasionally for power, with an average way, way up there—a player you’d expect to be starting an All Star game in the next few seasons, a player you’d be pleased to keep track of. And so it’s with tremendous sadness to report that World Enough, McLane’s follow-up to Same Life, is not the All-Star this reader had very much hoped for.

It’s not that McLane cannot still conjure dynamically gorgeous lines, like these from “Saratoga August,” in the book’s second section:

The specific ticks of raindrops

individuating

themselves against the eaves ledges roof

& beyond; behind

the indistinct fuzz of a general

rain. What you call fog

he calls a cloud. What you call rain

is raining every day

Still, for every section in which lines like the above sing and glimmer, there are huge chunks which don’t live, don’t move or tremble. Here’s lines from “Spring Daybrook,” the third section’s second poem:

sonic drift

the day’s heft

not so difficult to lift

when not bereft

Or from “Transcendentalism” in the fourth section:

another train another

sunset pulling the world

to its edge renewable

as the faithful

pledge faith in the

dawn they hope to see—

Please note: none of those lines are bad, they’re just flatter and flabbier than their Same Life siblings or peers and in the longer poems in this book, of which there are several, McLane delivers the goods in some sections even as other parts of the poem don’t gleam. Later in “Passage III” are these transfixing lines: “wavelap and lakeslap lick / the ear; the air carries / stripes in the / low precincts of sky—.” McLane’s sugar, too—the (over)sweetness of “Stars Arranging…”—takes in World Enough an almost McHughian/Lewis Carrolian bent. In from “It’s Not That,” for example: “It’s not that I’m opposed / to plastic bottles that won’t decompose // to malodorous phosphorus flows— / it’s not that I’m opposed // to what you propose—surgery on your imperfect nose // favelas blasted / with hoses—”

What World Enough is, despite the sometimes soft dulled-razor language, is an incredibly smart, idea-driven book, and the in-charge idea and/or force seems to be America, viewed both from within the country (“Meditation/Central Park”) and elsewhere (the book’s third section is resolutely French). McLane seems also to be, in some of these poems, setting herself up in the role of Chronicler of American Ugliness. In the third section’s “Au Revoir,” she writes “This is another first-world poem / annoying in all its presumption / its feckless tourism presupposing a home / and its hubris misregarding itself as gumption.” The guts it takes someone to paint herself in the ugliest of the book’s roles is evident too, throughout, by McLane’s willingness to offer and use biographical info for the sake of her art: ideas and considerations of motherhood thread throughout the book.

And yes, of course, to the “Coy Mistress” echo in the collection’s title: there are three “Passage” poems in World Enough (roman numbered consecutively, worth noting simply because there’s a “Songs of a Season II” though no first), and they anchor the book. Each considers the passing of time, of life, of people and loves. Here’s the thirteenth stanza of “Songs of a Season II”:

What happens in one place

Will soon happen everywhere

Wrote the man with the seamed face.

What happens in one place

Will not be confined to that place,

Will spread and soon displace

What happens. One place

Will soon become everywhere.

Though that poem’s subject is a relationship and its starts and stops, endings and cul-de-sacs, the sensation animating those lines—one event so seepingly powerful it turns all places into various harbors—could apply to the whole book. World Enough is full of questions of self at various levels—as species, as individuals, as citizens of various countries—and how those lines of self are, at best, fuzzily drawn, incomplete, and unable to keep the liquid of identity in just one place.

World Enough took me an exceptionally long time to come around to. Still: there’s plenty of strength in her work, and though her lines at times are weak, it’s largely a result of 1) the book’s ideas being massive and 2) the lines themselves having to bear up under the pressure of one of the best debuts in awhile.

Last: not coincidentally, McLane’s a reviewer and scholar—a phenomenal, Vendlerianly great reviewer and scholar (her first book was Balladeering, Minstrelry, and the Making of British Romantic Poetry)—and that her own work is stuffed with arched eyebrows and casual glances at other, older work should be no surprise at all. It should, however, be a source of some joy and pleasure if you’re in a hunt-for-clues sort of readerly mood.