Foreign aspects sometimes have a familiar whiff, and not just to Simic fans who have seen proof of his admission that Serbian poetry has affected his own. They have a familiar whiff because a number of poets in this collection have translated Whitman, T. S. Eliot, Apollinnaire, Emily Dickinson, Sylvia Plath and Cafavfy, among others.

Foreign aspects sometimes have a familiar whiff, and not just to Simic fans who have seen proof of his admission that Serbian poetry has affected his own. They have a familiar whiff because a number of poets in this collection have translated Whitman, T. S. Eliot, Apollinnaire, Emily Dickinson, Sylvia Plath and Cafavfy, among others.

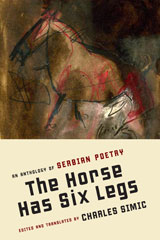

It’s no secret that I consider Graywolf Press one of the best and the bravest indies in the country. It has just issued an expanded version of The Horse Has Six Legs, an anthology of Serbian poetry first published in 1992, edited and translated by Charles Simic, Kay Ryan’s immediate predecessor as United States Poet Laureate. Simic is rightly admired for his poetry, his voracious literary appetites, his original, energetic , deeply learned criticism, and his unflinching honesty.

Simic introduces the new volume, and provides brief bios before each poet’s work. He also includes the 1992 essay that unlocked the earlier treasure chest. True to form, his claims for both collections lovingly concise. After arriving in the United States from Belgrade as a teenager, in addition to his college studies, his army stint, his teaching career at the University of New Hampshire, and his literary output in English, he spent more than thirty years reading and translating the Serbian poetry he liked best, and as the new introduction announces, he never stopped discovering writers.

“I sought poets whose work seemed to me of exceptional quality and whose poems were unlike any American readers were likely to encounter at home,” he says in the new essay . “I come across a poem in another language that strikes me as so fine, that the mere thought that people who care for poetry in this country are unable to read it seems to me an injustice that needs to be remedied.” He then describes translation as a ‘utopian project’’ again reinforcing what he’s said earlier about the challenges in bridging cultures and methods of expression. He also gives a quick, precise history lesson that supports the pages ahead, though every poem is strong enough and beautiful enough to stand alone:

Wind blows, one can smell the wild rosemary.

It seems to me my love is coming.

If I know from what direction

I’d sow sweet basil in his path,

Red roses where there is no path.

Let my love come by their scent,

By their scent and not by the light of day.

This is from a selection of late eighteenth and early nineteenth century oral poetry Simic believes originated much earlier, which helps build the scaffolding for what follows. Foreign aspects sometimes have a familiar whiff, and not just to Simic fans who have seen proof of his admission that Serbian poetry has affected his own. They have a familiar whiff because a number of poets in this collection have translated Whitman, T. S. Eliot, Apollinnaire, Emily Dickinson, Sylvia Plath and Cafavfy, among others. This adds weight to my conviction that the best poets in any language have understandable hungers for the tongues of others. I welcomed the stately cadences of Cavafy in poems by Jovan Hristic, as “To Phaedrus’ illustrates :

This, too, I want you to know, my dear Phaedrus,

We lived in hopeless times. Out of tragedy

We made comedy, out of comedy, tragedy.But the true seriousness, measures, wise exaltation,

And exalted wisdom always eluded us. We were

On no man’s land, neither being ourselvesNor being someone else, but always a step or two

Removed from what we are and what ought to be.O my dear Phaedrus, while you stroll

With noble souls on the island of the blessed,

Recall at times our name too.Let its sound resound in the resonant air.

Let it ascend toward the heaven it could never reach,

So that in your conversation, at last our souls may find peace.

In “The Tragedy is Over,” Hristic ends with a reminder that tragedy is ongoing:

But only for a moment. We will continue our play

happy that we were called to come out on the stage.

Branko Miljkovic, an exceptionally gifted writer, was a suicide in 1960 at the age of 26. “Shepherd’s Flute” is a curved web of longing, loveliness and sorrow :

Sweet fever of wind – troubled flowers,

You feel it coming. Plants, you bend again

On the trail of the drunken south and vanished summer.

Hurry, praise the world in a song.

Repent the day because of ungrateful flesh

Which gives back to the sun a shadow

And spoils the song. Give the solitary man

A bird. Under the empty heavens

The falconers cry. Call back the legend

The phantoms from the hills.

Let all the senses touch in a song

So that they may not lose freshness

In the night of the body. Let there be

Loss and less of the visible so that memory

May reign supreme. Empty what’s in my lap

And take my heart. Hurry, sing the eternal recurrence,

And fool misfortune.

Open the city gates, seduce the bird.

Under the empty heavens the falconers cry.

Simic’s generous passion is as contagious as ever, and it felt stingy to clip the piece. When he says that Radmila Lazac is one of Serbia’s best living poems, his credibility is bedrock, and it is encouraging to find feminist threads in her work. “I’ll be a Wicked Old Woman” would be welcome in feminist anthologies on my shelves from the sixties and seventies, still as gutsy and current as European counterparts :

Colts and stallions I tamed

With the flash of an eye, the flash of my skirt,

Passing over infidelities and miseries

The way a general passes over lost battles.

I’ll be free to do anything as an old woman,

Among things I still can and want to do

Like playing bridge or dancing

The light-footed dances of my days.

Many times here, Simic bestows a hearty shock to the intellect and the soul, not just to broaden one’s horizons, but to blast the horizon wide open, and in the process, discover and create new vistas. Vojislav Karanovic, born in 1961, author of six volumes of poetry, is the editor of a respected literary journal, and has also translated English literature. This book ends, fittingly, with his declaration, “I Saw, ” the final lines serving as a metaphor for his strivings, and those of fellow poets. It is also a reminder of what Charles Simic offers everyone who pays attention to him :

I saw, I’m sure

that shadows, that slides, grows distant,

and the light charging

as it shines on, illuminates everything in its own way,

everything inside of itself.

We are privileged to learn from the confrontational aspects of light and the subtleties of shadow. These lessons never lose their urgency, and Simic, with his ardor and expertise, is a towering example of what it means to be live in the realm of words, in a gloriously difficult world.

One response

What a lovely review.

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment.