McGlynn’s book follows an almost fairy-tale-type logic – the unknowing past-self of the narrator plays the part of the last wife of Bluebeard, searching out the hidden rooms, with the watching future-self unable to keep her from finding the closet of severed women’s body parts.

McGlynn’s book follows an almost fairy-tale-type logic – the unknowing past-self of the narrator plays the part of the last wife of Bluebeard, searching out the hidden rooms, with the watching future-self unable to keep her from finding the closet of severed women’s body parts.

I’ll tell you up front, I’m the kind of person who watched Memento backwards the first time, who gets in arguments about continuity in the time loops of the Terminator movies. So when I saw the title of Karyna McGlynn’s book, I Have to Go Back to 1994 and Kill a Girl, I immediately had to read it. Backwards, of course.

The book is a series of contradictions: poetic confessionalism with splintered, unreliable narrators. Multiple instances of one character. A film noir with a dash of sci-fi and teen movie angst. This book of poetry is all about fiction writers’ tools: plot, character, setting, and tone. Nothing is easily pinned down, however, in the mystery of who the narrator is and who she is going to kill. I think McGlynn’s mastery of storytelling makes it what so many poetry collections are not – a compelling, can’t-put-it-down read.

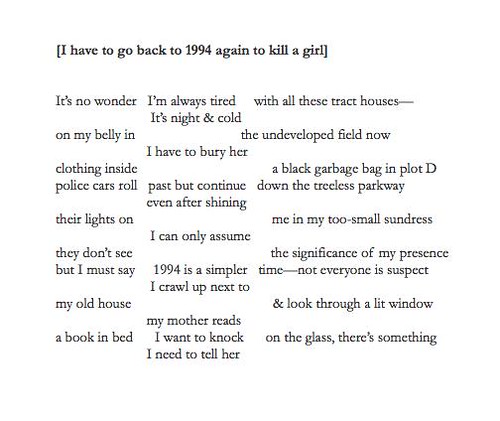

The title poem, “I Have to Go Back to 1994 and Kill a Girl” is written in three columns, a device the author uses many times throughout the book to emphasize the multiple nature of her thoughts and story. Here’s a picture of the poem as it originally appeared in Octopus Magazine.

Though the book overflows with pop culture artifacts from the early nineties, the edgy menace lurking in the poems counteracts the playfulness of the voice. The book follows an almost fairy-tale-type logic – the unknowing past-self of the narrator plays the part of the last wife of Bluebeard, searching out the hidden rooms, with the watching future-self unable to keep her from finding the closet of severed women’s body parts.

Another poem that entertains the outsider from the future interacting with her family is “I Show Up Twelve Years Late for Curfew,” which includes the following lines:

Trying to feel relevant now is a bit like

touching my own mouth shot full of anesthetic,

or forming the word “bouche” while drunk,

I survey the unnatural ocean of their new blue carpet

and try not to chew like a starving person.

This poem does a great job of describing the alienation of any adult who goes back to visit their parents, and feels estranged and betrayed by their parents’ lack of interest. The feeling that everything that is happening to the narrator is a familiar cycle, something that could happen to any of us at any time, helps ground a book in which the reader might feel uncertain of timelines or speaker identity.

It also represents what a good bit of the book appears to do: makes the known unknown, the familiar strange. The little detritus pop-culture reminders, the suburban mainstays that pop up in her poems comfort us, but the author keeps us off-balance with a parallel reminder of predation, danger and death lurking around every corner. Suggestions of child predation, rape, and murder litter the book, in sinister, indecipherable scenes, in almost homage to Twin-Peaks-style storytelling.

So, in this case, who kills Laura Palmer? Older men – fathers, grandfathers, nameless and faceless threats from the outside read about in newspaper articles – are the primary “bad guys” of the book. But there’s a sense that the person the narrator wants to go back and kill is her own childhood self, not any particular villain. The narrator’s contradictory impulse is to save this earlier self, though she seems to know there is no way to do so.

So, in this case, who kills Laura Palmer? Older men – fathers, grandfathers, nameless and faceless threats from the outside read about in newspaper articles – are the primary “bad guys” of the book. But there’s a sense that the person the narrator wants to go back and kill is her own childhood self, not any particular villain. The narrator’s contradictory impulse is to save this earlier self, though she seems to know there is no way to do so.

Half the poems are warnings, warnings about sex and femaleness; it is unclear whether the narrator herself is already dead and unable to escape her fate. “Erin with the Feathered Hair” – the person who dresses the narrator in the glittery tube top and kicks open the liquor closet – and the big-breasted, pointy-shoed narrator of “Would You Like Me to Walk Your Baby?” represent the threats of sex – and sexual hunger – for women. In poems where babies in churches are unsafe from a man when “even the iron bars won’t/ block his penis if he wants in bad enough” (from “The Nursery With Half a Window Up Near the Ceiling”) sex and violence seem to mesh and loom over the narrator’s younger self, who cannot be directly contacted.

A kind of Sixth Sense connection appears between the speaker and the children in the many scenes of threatened girls – can they talk to dead people? Is the motive force of this book self-violence a victim of sexual abuse feels against herself, or a wild declaration of violence against the forces of darkness? Is it a story of repressed memory recovered and rewritten? A hopeful intervention by a futuristic heroine? A story of a teenage girl’s life from a CSI detective’s standpoint?

A quote at the beginning of the book from the noir film The Lady From Shanghai gives us some clue: “Killing you is killing myself. But, you know, I’m pretty tired of both of us.” But it seems by the end of the book, the author returns to the movie Memento, as the speaker in “I Invented the Paleolithic Circumstances Beneath This” leaves notes pinned to her sheets to remind herself of who she is and what she has done. “You did this,” one of the notes reads mysteriously.

By the last poem, the narrator appears to have multiple personalities, speaking to herself as a child, herself as an adult, and an undisclosed “you,” perhaps her childhood attacker, perhaps a lover. In this poem the “I” narrator puts a pillow over a child’s face, seeming to put an end to the troubling memories and disturbances, to stop a future she knows will happen anyway. It is unclear whether this will end the nightmarish journey of the speaker, but since she says she “make(s) my own luck; I have to,” this could be seen as a cathartic, hopeful ending. Nevertheless, the most haunting images of the book – of frosted eye shadow, blood, girls in basements and crime-scene tape – outsize any attempt to piece together a clear narrative. Like the best fairy tales, or David Lynch movies, the disturbing glimpses into the dark edges of a woman’s life continue to flicker through our minds long after they are over.

Read Of All the Dead People I Know,” a new poem by Karyna McGlynn, in Rumpus Original Poems.