Crows circle, straight out of a novel by Kenya’s Nobel-nominee Ngugi wa Thiong’o. Only, the crows are circling the hotel pool, not the bush. I’m here in Nairobi teaching fiction for the Summer Literary Seminars, an organization that takes Americans writers abroad to study. I’ve taught for them three times—twice in Kenya, always in December.

Crows circle, straight out of a novel by Kenya’s Nobel-nominee Ngugi wa Thiong’o. Only, the crows are circling the hotel pool, not the bush. I’m here in Nairobi teaching fiction for the Summer Literary Seminars, an organization that takes Americans writers abroad to study. I’ve taught for them three times—twice in Kenya, always in December.

If I walk ten feet off the Kenyatta Avenue, away from the nonstop Toyotas and Celicas and Lexus, there are miles of real African bush town nestled in the arroyos of erosion, the one nearby that hides a 300-gallon car wash, the bar you just back your car into, and tin-roofed huts that boast a catering service. The crows know, even if the tourists don’t, since they seldom venture much past the thatched tables around the pool. But I can’t blame the tourists. The crows are big and scary, the kind that swoop down to eat pets.

Along the streets, car exhaust silhouettes the office workers plodding home. Many walk five to ten miles every day to their jobs, risking their lives not only by breathing the exhaust but also by crossing the streets. Both the traffic and the pedestrians ignore the lights. Being a New Yorker, I’m familiar with the massing-on-the-sidewalk technique, where walkers gather to step into traffic, and I’ve seen French women thrust their baby carriages into the streets of Paris, but I’ve never seen such chaos on both sides.

I take a break from teaching to visit a traffic victim, a South Sudanese whose taxi was hit by a matatu, a minivan packed with passengers. He is a Lost Boy, now a thirty-year-old Sudanese who, as a child, survived his country’s civil war by walking from Sudan to Ethiopia and then all the way to Kenya. The U.S. allowed some 4,000 Lost Boys into the country in 2000, making it the most successful resettlement in U.S. history. His cousin, another Lost Boy, had earned a master’s degree in economics in the U.S. but died in the accident. My friend is undergoing plastic surgery to put his face back together. He tells me someone stole his cell phone after the crash, so they couldn’t call for help. When someone did stop, they had to leave behind his critically injured cousin. The first hospital they found wouldn’t admit either of them because they didn’t have their papers with them.

Crows circle.

I take a taxi to Nairobi’s Kwani Litfest, a celebration of the sixth edition of one of the liveliest literary magazines on the continent. On the fourth day of the festival, Ngugi wa Thiong’o speaks for three hours on the eponymous Decolonizing the Mind, a book he wrote in the eighties encouraging writers to abjure colonial languages for their own. The audience, some two hundred students and professors, give him a standing ovation. Students attend classes in English but are careful to share their ideas in their own language at the pub. While this sounds ideal from a post-colonial point-of-view, Kenya still has PEV on its mind—the 2008 Post Election Violence—when tribal groups wrought havoc and murder across the country. John Ryle, editor of the Times Literary Supplement and director of the Rift Valley Institute that orients NGO’s to Sudan, noted the same tendency in South African universities. “It might as well be apartheid.”

The next evening at the Dutch embassy, I watch Binyavanga Wainaina, editor of Kwani—the first literary journal in Kenya—accept an award of 25,000 Euros. Although the magazine is primarily written in English, Swahili slang—known as “sheng”— shows up now and then, a hiphop blend of whatever trade language is the most eloquent, one solution to literary decolonization.

I come late to the final evening of the festival. Between the Kwanifest readings and music, I have a good chat with Khainga o Kwemba, the treasurer of PEN in Kenya. We speak about the terrible situation of Mexican journalists who are being disappeared or murdered by the dozens. The next day Khainga emails me from the hospital where he is recovering from a panga beating he received walking into the dark beyond the museum. His tape recorder and all his notes were stolen as well. Binyavanga tells me there are only three areas in Nairobi where the middle class don’t venture after dark, and all three are near institutions that seem very secure but are surrounded by darkness or bridges that harbor criminals. I have been reading Low Life about NYC’s Lower East Side a hundred years ago which chronicles the same situation. But even in the 1980’s when I moved into the neighborhood, you couldn’t get a taxi to stop. Now, of course, you have to dodge them.

One of my students, a Kenyan, is writing a murder mystery involving the sale of human organs. Her research suggests that if you take a taxi in Nairobi very late at night and you are not so sober you may very well wake up without a kidney. That’s the kind of grisliness you expect of Africa—not the brilliant progress I see at a thinktank the next day, where members are trying to redefine what African education can be under the aegis of the Aga Khan (the leader of one branch of Shia Islam). Yvonne Owuor, a Kenyan novelist, has worked for the last several years on a team to design a specifically African style of university, one in which all the complexities of language and learning styles are taken into consideration. The school and its support city will be built from scratch and both are planned to be self-sustainable. The talk is heady; the program has now passed into its implementation stage. Using the paradigm of the ubiquitous African cell phone usage, Owuor and others are leaping over our antiquated notions of education and rethinking it for themselves.

No taxis or crows in South Sudan. The windshield of the car I’ve hired looks as if it’s been machine-gunned instead of assaulted by rocks thrown up from the unpaved roads, and the only waste a crow could snatch from the thousands of displaced refugees would be the plastic bottles that line the gutters of Juba, the capitol. I decide I must go to South Sudan—Kenya is so close. Thirty-five years ago I collected the songs of the Nuer, a South Sudanese people. British anthropologist E. Evans-Pritchard founded the science of social anthropology on a study of their culture. War and life prevented me from traveling any sooner. Now it’s twenty days before their referendum to decide whether to become the first new nation on the planet since the breakup of the USSR and I want to play a small part in all the excitement, I want to present South Sudan’s Vice President Riek Machar with my book of the translations, Cleaned The Crocodile’s Teeth.

I have no appointment. It’s a Saturday. What makes me think I can muscle my way in to see the vice president of the largest country in Africa? Riek Machar is Nuer, and something of a ladies man, dubbed the Bill Clinton of Sudan. Deborah Scroggins wrote Emma’s War about his romance with Emma McCune, a wild British girl whom he married in the bush during his dashing guerilla days. Tony and Ridley Scott have optioned the film. Now married to a Sudanese woman, Riek is rumored to keep a white mistress from Kansas. I’ll play the white woman card and mention my last academic appointment was with Columbia University, and also the book was selected as a Writer’s Choice by the New York Times Book Review.

I reach Mario Jackson Mareng, Minister of Information, Public Relations, Culture and Protocol. Mario is staying one hotel away, in one of its many well-appointed air-conditioned cargo containers. When I ask him about relocation of the millions of displaced Southerners, he laughs and says the government can’t provide housing for its ministers–he’s been living here for the last five years. Educated at UCLA, he ran the country’s TV station and spent two years in a Khartoum jail as the reward for his writing.

“Your Excellency,” I say into Mario’s cell phone. What else did I say to the Vice President? Something acceptable, because right away he asks to speak to Mario. We take off for the V.I.P. Lounge at the airport where Riek is waiting to greet the president on his return from last minute negotiations in Khartoum.

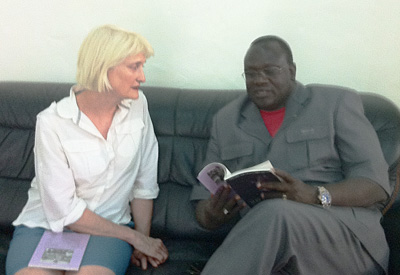

I see no guns at the V.I.P. Lounge, no bodyguards, no soldiers. The ministers are seated in huge leather armchairs inside ropes that keep the riffraff out of NYC clubs. Riek kisses me like an old friend. He’s at least six-five, still powerfully built and cute, with a gap between his teeth. I flirt as best I can with the book of translations as our subject. “I attended the funeral of a paramount chief last week in Fangak and decided I must do this very thing,” he says. “The men sang our history four hours.” I ask whether he still knows any songs. He smiles. “They are the ones from when I was a very young man. I composed them myself.” We exchange a laugh. They would be songs in praise of himself, advertisement for the girls, hip-hop with spears. But he was at university about the time most Nuer men were courting; he had to learn other wiles. He leaves to greet the president—”Stay, stay,” he insists—and when he returns, he pats the seat for me to sit next to him, smiling a guileless smile that can’t be real or he wouldn’t be alive today. I write a dedication in the book for him while he practices pronouncing my name. “We should start a book club,” he suggests to Marion, and the interview’s over.

What have I done, in terms of Ngugi’s treatise, to complicate the literary scene? Kenya shares a border with Sudan but Sudan is not really East Africa, it’s all of Africa, stretching from the Red Sea to the Congo, the same size as all the U.S. west of the Mississippi. Thirty-five years ago, Kenya had few writers other than Ngugi, and most of its literary work was preserved in its oral traditions. South Sudan is Kenya then. Aside from poet Victor Lugala, whose book Beating the Drums of War Mario handed me for inspection, the country has very few authors of the printed page, and almost no resources to print them. On my last trip to the country, the most prized possession of many South Sudanese was a tape deck, used to play back their own songs, not Michael Jackson’s. In the future I imagine the emerging author will publish on Africa’s ubiquitous cell phone. But in English, or his own language? South Sudan has more than 200 languages, and many of those have distinct dialects. Technology doesn’t support unusual orthography—but it didn’t support the strange emoticons either. Perhaps a tech solution will emerge.

But in the meantime, how do writers writing only in their own language help a country just starting out? Some forty years ago, Sudanese diplomat Francis Deng, Under-secretary General in the UN, translated the Dinka songs. The Dinka are the Nuer’s main rivals and as close culturally as cousins. They have been killing each other as recently as last January. If the Dinka read the Nuer songs, will it rouse them to battle or lead them to recognize themselves? Songs have been used as evidence of incitement in Sudanese courts. Unity is a fragile construct. Writing in another language didn’t muffle Joseph Conrad, I think, watching a parade of Lexus cars pass the hotel.