“Censor the body and you censor breath and speech at the same time. Write your self. Your body must be heard.” – Hélène Cixous

“It’s almost like our tits carry the burden of this culture of death.” – Kathy Acker

Let’s talk about boobs.

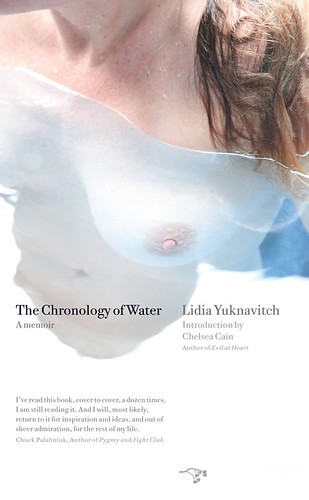

When my editor/publisher was choosing a cover for my forthcoming book, The Chronology of Water, she asked me if I had any ideas. I did. In my possession was an abstract series of unusual photographs taken by Andy Mingo depicting a woman’s body in water. Since the central metaphor of my book is swimming, I forwarded the photos to my editor. She loved them. And from among the photos, she chose one for the cover of my book.

It’s a boob.

With full frontal nip.

Yes, I will show you in a minute.

What happened next of course is that the book went into design and production. We all understood we were making a cover that was at the very least atypical. Possibly controversial. Absolutely, as it turned out, problematic for some in terms of visually showcasing the cover. For example, Facebook does not “like” naked boobs.

At every stage, the question why haunted me. I mean, considering the world we currently inhabit—and by that I mean the high-capitalism consumer-culture world, in which women’s bodies no longer stand for something bought and sold, but unalterably ARE the thing being bought and sold—why would a boob matter anymore?

Further, considering the absolute addiction our culture has to sex and violence on television, film, and in certain genres of commercial books, many of which exhibit plots that are based on the classic rape/murder-threat-against-women trope, so eloquently delineated over the years by waves of feminist film and literary criticism, what threat is a single tit?

Still, booksellers and professional literary folks began to warn both me and the editor/publisher that the books would not be displayed or sold in certain stores or venues or even … states.

Yay, Texas.

Let me stop here and lay something out for you: my publisher/editor is Rhonda Hughes. She runs Hawthorne Books in Portland, Oregon.

And she has big balls.

Big enough balls to print the cover she wanted, to take on the naysayers and to come up with a solution for the display problem. Interestingly, it’s called a belly band. Which basically amounts to a neat charcoal gray “blanket” that goes around the book and covers up the boob. Sly one, she is.

Here are the two covers, with boob and with discretely covered boob:

About these covers, I am ecstatic. I love Rhonda Hughes, I love Hawthorne Books, and I love both covers. For different reasons. I mean, that orange type on the charcoal gray looks swank, yes?

But, as it turns out, there is an unsettling gender issue at play when we talk about a book cover entering the market with a nude woman on it.

Specifically, if a woman, or in this case, two women—since I have the luxury of creative input with this most exquisite editrix and press—quite consciously make the decision to present a female nude on the cover of the book they intend to seriously enter into the market, a crisis of interpretation arises.

I mean that in the Derridian sense.

The crisis is this: When it comes to representation, it is not entirely OK for women to insist upon the representation of their own bodies in their own terms. And by OK, I mean culturally sanctioned, commercially viable, literarily or intellectually respected. And when I say in their own terms, I mean with a specific representational validity and aim, and without apology. You are just going to have to trust me with this next statement when I say, virtually NO agents or mainstream or commercial presses would touch this cover. Few literary presses would. Ditto for some of the sexually explicit content in the book.

There appear to be two main reasons for this. The first involves when and where and why you can present nudity in America, and its relation to our notions of obscenity. Put more simply, if it’s buck naked, it’s “pornographic.” However idiotic that notion is.

A very smart and successful person I know told me, “Oh my God! You can’t have that cover! No one will want to be seen holding it in public, you know, like on a bus or at a restaurant. And stores won’t sell it! And I was planning on giving it to several of my friends who are very important women over fifty!”

Hmmm. The same bus, with the potential person holding my book in it, is barreling by billboards with giant (yet tiny!) women in recline, half-clothed in black velvet to sell booze. Further down the road there is a billboard with a hot chick in a bikini and a Bud Light can pressed up against her rack. On the corner is a woman literally making her living with her body. And the woman next to me? On the bus today? She’s reading Vogue. Have you looked at Vogue lately?

I know what my friend meant though. She meant people would be embarrassed to be seen with a boob book in their hands. Though it’s true enough that LOTS of other people would be downright skippy and proud to hold one in public and wave it around—I have a boob book! HA!—she also meant, at least implicitly, you can’t have a nude woman on the cover of your book if you intend to be taken seriously by the wizards in charge of marketing and consumption in the literary industry. With of course some notable exceptions, where nudity is, you know, HOW the thing is sold.

Ironically, while maintaining a rather puritanical attitude toward the naked body, America is one of the largest producers of pornography in the world. Not to mention our first rate success at using naked women to sell EVERYTHING UNDER THE SUN—the glamorous, stick-thin provocatively dressed or barely dressed unattainable anorexites and push-up-bra heads among the chief bestselling images.

The second reason is slightly more covert, hiding under the cover of a book cover. Comic book and pulp fiction covers have consistently made use of the half-clothed or unclothed buxom beauty, but somehow those forms are considered “low art” enough to earn them a kind of outsider status in terms of the use of nudes. They are a few steps up from porn, and an inbred kin of the good kind of trashy. So they get a pass. Phew. Similarly, you can find a variety of semi-hot, shadow-nude women on the covers of certain pigeonholed genre commercial fiction, as noted earlier.

I think there is another reason. The individuals who have most often contacted me with danger! danger! warnings are women. I don’t think male readers mind a boob book cover. I could be wrong about that. It’s just a hunch. But the women who have spoken to me directly about the boob cover have fallen into two camps: either they think it is beautiful or radical or just fine—no biggie—or they think I’m shooting myself in the foot (or boob) in terms of buying and selling my work—the terms that are already stacked against women in the literary industry.

See VIDA’s statistics on women in publishing. Also see the history of feminism in America.

Let me tell you why I became insistent about the cover. My memoir is, at its heart, about how I survived the life I was dealt, kind of like we all do. The central and enduring metaphor that holds the story together is swimming. And the central site of meaning in this story I have told about making a self from the ruins of a life is a body. A real body.

An eating, fucking, shitting, peeing, sweating, bleeding, body.

If anyone bothered to ask me, I would tell them this: I consider the body to be an epistemological and ontological site. A place where meaning is generated and negated and where the terms of being and non-being are endlessly played out. Not to conquer and assert the “I.” But a site of endless corporeal signification.

And yes, I mean that in the Kristevan sense.

I just get the feeling not many people are going to ask me about Kristeva when they look at the cover of my book. You know?

Part of the dire problem is that it is quite difficult to make the assertion that one owns ones mode of representation and ones mode of production and the meaning making operations of ones body as a woman.

Yes, I mean that in the Marxist sense.

As it turns out, those ideas—commodity, labor, production, distribution, epistemology and ontology—seem unequivocally reserved for the realms of philosophic discourse, on the one hand—and in particular, whether we want it to be true or not, a rather patriarchal philosophical discourse, and on the other hand, market driven rules and regulations, another patriarchal bastion which does not include women owning the signification modes.

Although, somehow or other French women intellectuals are allowed to make such assertions: Kristeva, Cixous, Irigaray, Duras, de Beauvoir (is it in the wine?).

Oddly, in America it’s apparently not OK (see earlier note on what I mean by OK) to claim the body as the “site” of meaning-making that I am suggesting, unless I follow a very particular male philosophic trajectory, or, worse, a Christian master narrative in which women figure quite disappointingly. I mean jeeeeez. The two Marys? What promise! What radicalism! Alas, subsumed by the story of a pretty and charismatic man and a larger than life father. Perhaps that is part of the reason the pregnant and maternal body is relegated to the sphere of the domestic—where, as luck would have it, no form of epistemology of ontology is allowed to be born—EVEN THOUGH without Mary’s actual body, god is just another guy standing around with a dick in his hand.

Similarly, it is apparently not OK to circumvent the sexually exploitative representation of female bodies so characteristic of television and film by presenting it as a speech act—as an act of representation designed to tease forth the relationship between signifier and signified, or the ground upon which the story of a woman’s body and the image of a woman’s body are precisely articulated by and through a nudity not bound to poles—no pun intended—well maybe just a little—of not just signifier and signified, but also of capitalism and the buying and selling of women’s bodies as objects.

See Sut Jhally and Killing Us Softly 1, Killing Us Softly 2, 3, 4, etc…

Also, see Zizek on woman as father lately.

But maybe you think I’m full of shit. Maybe the boob and nip on the cover are simply recommitting the age-old Sex Sells paradigm. Putting aside for the moment that the publisher is being asked to cover it up in many cases, to answer that charge one must look seriously at the cover. I mean closely. I mean using critical thinking and close reading. Hold the book boob up to your face.

Jeez—not that close. Ew.

That body ain’t no airbrushed hot model’s body. That boob is not “man-made.” That nip isn’t quite right—and what’s not quite right about it is that it’s a real nipple. It sits how it sits, is sags a bit, there are imperfections all around it. Also, I have it on good authority that it’s the boob and nip of a woman closing in on fifty years old. If Hawthorne Books wanted to exploit a naked woman on the cover of my book to sell the hell out of it, they definitely should have hired a … you know, market-tested hottie.

But I admit that’s a little bit of a pot-shot answer.

A more serious answer is: this is what happens when you put the mode of representation, production and distribution in the hands of, well, smarty women. There is no silicone or push-up bra or tantalizing sexualization, fetishization, or ironic stance. There are freckles and saggages and discolorations.

The cover is showing you something about an ordinary woman’s body. Inside, the text is saying something about how an ordinary woman found a self by and through her own body. Between seeing and saying, a dialogic exists.

Yes, I mean that in the Bakhtinian sense.

The boob image, and even more gasp-worthy, the sexual explicitness of the story inside are in dialogue with all the images and stories that have come before. Other women, other women’s bodies, other boobs—boobs that have been endlessly suckled and fondled and kissed and made full or sagged or been riddled with cancer—mothers, sisters, daughters, lovers. Grandmothers even.

I’m going on and on about a boob.

But the thing is, it’s just not a boob in the way we are used to thinking about boob. Particularly in America. Look at it. Face off with it. And if you get tired, or cranky, or disturbed, or bored, just put that cool little charcoal cover with the aesthetically pleasing orange type back over it.

The difference between this boob and other boobs out there today? This boob is talking to you.

36 responses

“Ironically, while maintaining a rather puritanical attitude toward the naked body, America is one of the largest producers of pornography in the world.”

And guess which states are the largest consumers of online porn in the United States? Overwhelmingly it’s the conservative states, led by Utah, home of the family-values Mormons! Those wacky Mormons are the number one consumers of adult websites in America, with 5.47 adult content subscriptions per 1000 home broadband users (and the most clueless– who actually pays for “adult content subscriptions?”).

http://abcnews.go.com/Technology/Business/story?id=6977202&page=1

One doesn’t encounter much writing of this nature and quality, outside of the French writers some of whom are quoted.

Abjection, indeed . . .

No inkling of naturism here, whose practitioners have a significant connection to this subject despite their untheorizing repetitions and politically as correct as possible constructions.

Okay, I’ve looked around and encountered more writing of this nature and quality (if not enough). It needs to get around. A lot. Endless coporeal signification indeed.

Excellent and provocative piece, Lid! As you know, I had just a small glimpse of a nipple on the cover of Slut Lullabies, and I cannot count for you how many times people remarked to me that they had gotten weird looks on the bus/train while reading it. Some of these people were embarrassed by that, and others seemed tickled, but still, the cover became a bit of a fixation . . . I was also asked about it so often in interviews that I literally had to start asking people in advance not talk about the cover because it was becoming redundant. I love the piece of art that was on my cover–and I love Andy’s photo, too–but even knowing our cultural obsession with the female body, I admit I emerged from the whole thing a bit shocked by how much attention one corner of a nipple can elicit, even in indie lit circles. Wow–you are in for a wild ride, I suspect, with your full-on-hanging-out-there-lushly boob!

BTW, I’m devouring the book right now. You’re making it hard for me to get anything else done!

And it’s always nice to see the French feminists make an appearance on The Rumpus!

I really, really loved this. Thank you for writing it. And for bearing and baring it. May your book enjoy its soon-to-be-hard-won success.

In a bank line recently, I was looking through a naturist magazine I’d edited. The woman next to me looked down her horned-rimmed nosiness at the cover and snorted, “There are children present.”

“That’s unfortunate for you,” I replied.

I should be interested to hear reactions to the book’s cover. But there isn’t a variation on the hand-wringing “What about the children?” that I haven’t heard. I wonder if the blanket is too clever by half. At least it’s gray.

I do understand that in some cases, you can’t sell a book by its cover.

The cover, the un retouched image makes me want to read it more. I was just discussing this with a friend of mine and I often don’t want to read memoirs by women when the cover images are too perfect. Thank you for posting this.

That cover attracted me the first time I saw it a few weeks ago, and I had many of these same thoughts—largely because of the controversy a few years back about the “Summer Fiction Tits” cover of Fence, along with editor Rebecca Wolff’s great response to the controversy: http://fence.fenceportal.org/v9n1/text/editor.html

Excited to read the novel. Am a Hawthorne Books fan myself (okay, I only read Clown Girl, but they have a great catalog).

On another note, my fingers are crossed for Powell’s Books…

The cover is a stunning work of art. The essay is a stunning work of art. And I am waiting for the warm water season to begin reading The Chronology of Water, undoubtedly a stunning work of art.

It’s interesting that you mention the Facebook thing. It’s such a huge part of marketing nowadays that it actually can have such an effect. When we were trying to develop the latest Beatdom cover, we were for a long time sure that it would feature nudity… but then we would have been forbidden to put those pics on Facebook, which is where we spread most of our information to our readers.

It’s funny, also, that people can be offended by a boob. Or a nipple. No, actually it’s not funny. It’s sad. Very sad.

It’s not that Facebook doesn’t like naked boobs, as Lidia puts it. It’s much worse than that. Facebook pretends to have a policy on photos but actually doesn’t. It deletes images with a capricious irrationality for specious reasons that its immature spokespersons don’t even understand. For clueless carelessness and arrogant ignorance, there’s nothing like Facebook.

I’ve been dealing with this problem for nearly four years. If you don’t believe me, have a look at a collection of what Facebook has deleted in one category as obscene, at: http://www.tera.ca/photos16.html and similar pages there. Those photos include some of artwork in museums, animals, and my favorite, a clothed woman sitting on her couch with her clothed children.

Facebook promotes body phobia and misogyny through a totalitarian practise of censorship that beats just about anyone.

Well. Fucking. Said. Lidia.

What I find most intriguing (galling? frustrating?) about this subject is that it is actually not “the boob” that causes the furor, it’s the nip. And because it’s not a nip behind a wet T-shirt or silhouetted under clothing, it is somehow shocking or “too much” or too “out there.” Gasp. I am so glad to see a real photo of a real body for once. I, for one, cannot wait to read your book.

Amazing the attraction and commotion a lump of flesh can cause! I find your book cover (the one without the “gray matter”) very natural and innocent – it’s the viewers’ baggage that makes it otherwise. I wrote about the use of the boob in a more prurient manner: http://cerebralboinkfest.blogspot.com/2010/12/sluts-and-lesbians-images-of-ancient.html

hey you all, THANK YOU for reading and taking an interest! i really appreciate your comments. i identify with all of them…feels like a new wave of repression is growing–i remember the last one. one of my short story books was in a little pile on the desk of jesse helms when he attacked the NEA…something smells similar.

GINA!! i know!! same issues…sigh. this is my preemptive strike…maybe i’ll carry it around in my back pocket so i can whip it out. ha. at any rate, thank you all so much.

I really loved this essay and am glad to read the discussion in the comments as well. A small–maybe silly–question — why boob and nip? Why not breast, nipple? Especially breast. Just wondering.

oh i just got used to saying them…when i grew up “boobs” was the nomenclature. at least at my house. ha. and the anatomically correct terminology gets a little medical sounding for me. but thank you for reading!

Terms have many kinds of use: formal/informal; medical/non-medical; serious/jocular; neutral/ironic; standard/jargon; technical/politically charged; prosaic/poetic; educated/folk; distant/friendly.

Not all of those are even dichotomies. There are overlaps, ambiguities, mulitple meanings, and hierarchies. Maybe it’s surprising we can communicate at all.

Nice essay. The reality is that it is very difficult for a woman to be taken seriously while naked in our culture. I suspect that may have been part of the opposition from some of your female friends alluded to in your post. There is this really creepy abusive icky thread in our culture when nude models and/or porn stars try to do something other than titillate. So I can see the point of putting boob on the cover in the sense that the whole whore/mother paradigm will never change unless people learn to accept the totality of women, and men for that matter. But there is a risk that some people will just look at the book and see boob and never pick it up because of shame, jealousy, fear etc. I’m not sure if after i buy your book whether or not I will read it on the bus, maybe in Portland, probably more from fear of being seen as some sort of pervert. Most people when they see boob (a term that really is growing on me although my nomenclature was generally just tit) only see porn which is wrong for whatever reason.

thus the beauty of the sly belly band.

This is a wonderful piece; I will certainly seek out your book.

Here’s a recent example of boob censorship, when the boob was being presented in a non-standard way: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/14065706/ns/health-womens_health/

People just can’t deal with boobs as simple body parts.

excellent link!

Beautifully expressed, like breast milk.

beautiful comment.

A brilliant idea,this cover,controversy does sell books and selling books means your message gets out. Well played.

i’m reading the book with TRBC. digging it pretty much. i was actually a little taken aback by the grey band. upon the book’s arrival in the mail, i peeked under the band and though WTF? i wasn’t offended at the cover-up, i just didn’t understand why the fuss. it was overkill. but then i read this piece and now i sort of understand, though i think it’s sad. you’re pretty great. thanks for the book.

Just for interest . . . Hawthorne Books sells the book at a reasonable price ($16), but to send it to any Canadian city, it doubles the price, whereas to send it to much, much more distant American cities, it charges nothing.

That absurdity has cost it a customer, and probably more than one. It does not cost Hawthorne Books $16 to send a book even airmail to Europe or Australia.

That may be HB’s way of saying it has the same attitude towards the rest of the world as most Americans do. I’m not interested in supporting that. I’ll get the book another way.

hi paul–i’ll pass that along…i see what you mean…

mamma loves canada…boy howdy.

Great article, Lidia. So looking forward to digging into this book. There’s certainly a lot of hypocrisy going around. I still don’t understand how prostitution is illegal, oh wait, except for in Nevada. Or, parts of Nevada. Over HERE buddy, not over THERE. Whatever. The cover of your book is compelling, and appropriate to the content. The US is a bunch of prudes. When they aren’t privately oggling one thing or another. Oh man, I feel a rant coming on. YOUR BOOK. Can’t wait. I will wave that cover wherever I go.

“This is what happens when you put the mode of representation, production and distribution in the hands of, well, smarty women. There is no silicone or push-up bra or tantalizing sexualization, fetishization, or ironic stance. There are freckles and saggages and discolorations.”

To that, I disagree. To assume “well, smarty women” would only move toward some kind of “authentic” representation of sexuality is simply furthering sexual misunderstanding. It is also, not to mention, offensive. The body is and never will be a pure, unfettered space. Like Irigaray wrote in regard to language, the body is a construction site, a place where building and choice must occur in order for there to be dialogue.

Choosing to embody or put on a cover a representation of “tantalizing sexualization” should not necessarily correlate with the intellectual capacity of that body’s brain.

So, I’m late to the party here – somehow I missed this post – but it was February – what can I say – I was probably shoveling snow.

I got my copy of TCOW the other day and was puzzled by the band, like Betsy above. Last night I posted about it at WWAATD and someone nicely told me about this post. I’m glad he did, because this is a wonderful discourse on the convoluted power of images of bodies or body parts.

I was going to ask you WHY about the tasteful charcoal boob cover-up when we talked briefly at your reading. But then water started squirting out of my eyes and I felt it best to retreat. But this answers that question, so thanks!

I, too, am late to the discussion, but read a recent review of TCOW on a blog and followed my curiosity here.

I agree with John–nicely played scenario with the cover, since it definitely would create controversy, which brings attention, even as it fits the subject matter. And can be explained in such lovely literary terms. Beautiful essay.

An interesting dichotomy, too, in that you use a masculine term (big balls) to describe Hughes’ decision to go with the boob cover, in an essay limned with the strength to be found in a woman and her body. I find that worth some thought on my part.

And is this the correct discreetly\discretely usage? “Here are the two covers, with boob and with discretely covered boob:” Or am I confused about how you are using the word?

What a welcome breath of fresh air. The world needs more women like Lidia.

I should have mentioned that Paul and I work together at TERA (where we featured your book), on what is now becoming known as “Free the Nipple” or even the Nipplelution, the liberation of the female nipple from a few centuries of having it cast in shame. The struggles Lina Esco is facing are a good example of that. (Banned by Facebook, Instagram and Google + – naturally).

http://fundanything.com/en/campaigns/freethenipple

I appreciated the philosophy. I don’t have any problem with ‘boob’ even though it has derogatory connotations in other contexts, but it is widely used by women themselves.

I did however have a problem with ‘nude’. Men’s chests are not nude, only women’s are apparently – even after a double mastectomy. ‘Nude’ should be really be reserved for actually naked – the conflation adds to the shame inflicted on women, the curse of Eve.

I too had a problem with women being referred to in terms of male anatomy – and I recalled the feminist summary of this – “Why do people say “grow some balls”? Balls are weak and sensitive. If you wanna be tough, grow a vagina. Those things can take a poundingâ€

I frequently explain the dichotomy you outline, by saying Women as Object OK, Women as Subject – not OK.

Thank you once again for raising this important issue that creates so many self image problems for women and girls. I will pass on your comments to Facebook, and help to publicise your work.

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment, or log in if you’re already a paid subscriber.