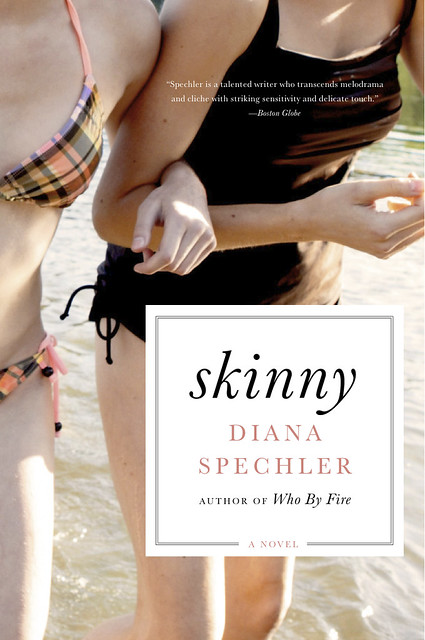

After I’d been working on my second novel, Skinny, for three years, and by “working on,” I mean writing aimlessly like Jack in The Shining, a friend of mine requested a favor. He’d been cat-sitting, a job that would last another six weeks, and he needed me to take the cat, just for a night or two, while he moved into a new apartment.

After I’d been working on my second novel, Skinny, for three years, and by “working on,” I mean writing aimlessly like Jack in The Shining, a friend of mine requested a favor. He’d been cat-sitting, a job that would last another six weeks, and he needed me to take the cat, just for a night or two, while he moved into a new apartment.

I didn’t know how to cat-sit. Although I had no proof, I thought I might be allergic to cats; cats struck me as allergenic. I also worried that cats didn’t like me. The winter before, my best friend’s cat had peed on my down coat. Plus, I was averse to the idea of a litter box—what a disgusting thing to inflict on my living space. But my most pressing reservation was that I had a book to write—a novel based on the summer I worked at a weight-loss camp.

Whenever I suffer from writer’s block, I think everyone is conspiring to distract me. Never mind that I distract myself perfectly well, spending hours in front of the mirror, plucking the one eyebrow hair that stands between me and that modeling contract, watching my blank computer screen remain blank, examining a Facebook photo album full of strangers who look fulfilled. When I’m blocked, I read every invitation as an imposition and every favor request as an insult. Don’t people know how busy I am?

But because I had trouble articulating to my friend what exactly was making me busy, I heaved a great, theatrical sigh and agreed to cat-sit.

That night, my friend and I ran around his apartment, chasing the cat—a solid black silhouette of a thing with some generic, monosyllabic name. The cat made threatened-cat noises and scratched deep red stripes into our arms. Finally, we cornered him and shooed him into a laundry bag.

Minutes later, sitting in the back of a taxi while the cat squawked and pawed helplessly at the fabric, I gulped back tears. “Hush, cat,” I whispered. “Shh.” I knew how to talk to dogs. And to babies. But cats were a whole new ball of string. I looked at the bag. “Isn’t that such a good boy,” I said.

That part of the story is no fun to tell, because where I expect sympathy, I meet judgment: You stuffed a cat into a laundry bag?

In the rearview mirror, the cab driver narrowed his eyes into sticks. When he dropped me off, I carried my bundle up three flights of stairs. And then… I, um, let the cat out of the bag.

***

Hours later, I woke to a morning like any other. The sun was streaming, unwelcome, through my windows. As usual, I could hear my neighbor’s television. (To celebrate his love of television, my neighbor blasts his, at top volume, always.)

The cat was curled up beside my head, blinking languidly at me. But when I made eye contact, he rose. Then, in a black streak, he zipped athletically around my studio apartment, his claws scraping the hard wood. The lap took him a total of three quarters of a second. After completing it, he embarked on another, and then looked at me, as if to say, “Let’s do this thing.” Although just the night before, he’d been a quivering lump in a bag, today he was free and fearless.

I envied him.

I wished someone would free me—from my “writer’s block,” a nom de plume for fear. I feared that if I finished the novel, in light of its topic, readers would assume that I had body image issues. Of course, that assumption would be correct. I’ve grappled with body image for most of my life. Which is why I wanted to write the book. But I couldn’t write the book. But I needed to write the book.

Lying in bed, facing off with the cat, it occurred to me that something was different: The dread I had greeted morning after morning for three years, the sickness in my stomach that represented the mess of my manuscript-in-progress, was absent. In its place was my novel, the whole of it, scrolled open in the air in front of me like a divine revelation. It shimmered a little in the early morning light. I could have poked it with a stick.

I glanced at the empty laundry bag in the corner. I sat up, shook off my blankets, and swung my legs over the edge of the bed. And then I called my friend, the original cat-sitter. “I would like to keep this cat for a while.”

“Have him.”

“Thank you,” I said. “He’s my muse.” I hung up and tapped the cat’s claws. “Aren’t you, Scrabble Toes?”

He arched his neck and swallowed some air.

“That was cool,” I told him, patting his head.

I cleared my schedule, vowing to leave home only if work demanded it, to abstain from alcohol and even yoga. I had to preserve my creative trance, to transcribe my novel before it disappeared.

I began typing a thousand words a day, and then two thousand words, three thousand, four thousand.

The cat sat beside me while I worked, and every night, he cuddled up to my head when I drifted off to dream of my novel. Mostly, I called him Scrabble Toes, but sometimes, in homage to his black hair and green eyes, I called him Mr. Black and Green. I chanted at him, “Mr. Black and Green! Cutest cat I’ve seen!” And finally, I settled on the name Neo, like Keanu Reeves in The Matrix—the scrambled letters of “one.” (“You are The One, Neo,” Morpheus says.)

My Neo was, no doubt, The One. He was the most beautiful, magical cat on earth. “Neo,” I often said, “you are a beautiful, magical kitty face!” I picked him up under his cat armpits, held him aloft, and kissed his little mushroom nose. “I love you, Neo!”

My manuscript grew to sixty thousand words, then seventy thousand words. Eighty thousand words.

I wondered: Was I going crazy?

Yes.

Okay, but truly, irreversibly crazy? For how long would I communicate with an invented cast of characters, singlehandedly funding Seamless Web, stroking Neo’s kitty spine while gazing pensively out the window? Was this how people became cat ladies? So as my cat-sitting stint wound down, I anticipated the end with mixed emotions.

Right before Neo and I were torn apart, I wrote one of the most unsettling scenes of my novel: my protagonist driving to an all-you-can-eat buffet and bingeing—graphically—filling up plate after plate with cheap, greasy Chinese food.

Pre-Neo, the scenes of my novel that I wouldn’t write, the parts I’d hidden from because they felt the most exposing, involved my protagonist losing control. But ever since Neo had sprung from the laundry bag, I’d relinquished control. Six weeks later, I had a whole rough draft.

***

I’d never met Neo’s owner, whom I’d come to think of as Neo’s Dad. All I knew about him was that since acquiring Neo, he’d succeeded as a Broadway actor—further evidence of Neo’s muse status—and that for months, he’d been on the road, performing in some musical.

I’d never met Neo’s owner, whom I’d come to think of as Neo’s Dad. All I knew about him was that since acquiring Neo, he’d succeeded as a Broadway actor—further evidence of Neo’s muse status—and that for months, he’d been on the road, performing in some musical.

When he arrived at my apartment, he looked like an authorized cat handler. This was not a man who would brandish a laundry bag. Armed with an official pet carrier duffel, he donned protective gloves that couldn’t be scratched through. “What you’re going to have to do,” he said, “is back him into the bathroom, and then shut the door. Then I’ll slip in there and corner him.”

He seemed so earnest. I decided not to tell him that I’d renamed his cat.

“I can just pick him up,” I said, “and put him in the carrier.”

I bent and scooped Neo into my arms. He vibrated and nuzzled my neck as I said goodbye into his black triangle ear. A month and a half after the initial chase and capture, I didn’t love the idea of stuffing Neo into a bag, but I did what I had to do as a montage of our relationship played in my memory. The first time he licked my cheek. The times I’d held his tiny paw. Our long days together in front of my laptop. I resisted the urge to whisper, “Thank you, Neo,” and tried to look on the bright side: I would no longer have to wipe cat litter from the soles of my feet before putting on my socks.

I couldn’t help telling Neo’s Dad, “Any time you need a cat-sitter…”

“Right. Thanks,” he said, zipping the duffel closed.

I shut the door behind them. Then I pressed my ear to it, in case Neo whimpered a final message.

Nothing. Just my neighbor’s television. The specific grief of a laugh track.

I had printed my novel that morning and the stack of pages sat on my bedside table. I looked at the stack with brief trepidation before crawling into bed. The apartment purred with emptiness. I pulled a cap off a pen with my teeth. I relished the weight of the pages on my lap. In this way, I resumed my life.

9 responses

Very nice. I enjoyed this.

I love this. I am chipping away at writer’s block myself now, so nice to read of your emergence from it. (Although I am way too cat-allergic, in every way possible, to borrow one.)

I loved this story and I really DON’T love cats (but maybe that’s just because I haven’t found my muse cat yet).

When I was a sophomore in college I had a friend who was just incandescently beautiful, incredibly smart, quietly confident- guys just fell over her left and right. She was a person bursting with magic, I was half-convinced she was fairy princess switched with a human girl at birth. Magic Girl lived in a studio apartment near the apartment and when she decided to go abroad to Italy her junior year, I agreed to take the studio over from her. Two and a half weeks into living in the new apartment, I met the handsome, hilarious, brilliant, wonderful love of my life, we’ve been together five years now. I’m convinced that Magic Girl left some of her magic scattered around the apartment for me to benefit from. I say that being a through and through skeptic, I don’t particularly believe in numerology or astrology or “signs from the universe” or circumstances and events that are “meant to be” but I can’t deny that there are entities that come into our life and mysteriously, unexplainably make them better. I’m glad you had your Muse Cat, and of course, I’m glad I had Aphrodite’s Studio Apartment 🙂

I disliked an excerpt I read of Skinny, but I enjoyed this.

This is a great little story – thank you!

Great story. Alas, my two dogs are easily trying to prevent me from working, so I found a better muse for myself. It’s a beautiful little alabaster owl. His name is Owlabaster. Hey, I’ve never claimed to be particularly creative, but he’s a real help when I’m staring at a blank screen. He’s small enough to fit in my hand and his eyes provide a lingering and judging stare that implore me to keep writing. If I’m in a really tough spot he site on the edge of my laptop and stares at the screen. I imagine he’s counting the words and I know that I have to please that little inanimate object, and sure enough, everything gets on the page.

wow !

This was so sad for me, your kitty friend leaving. But I’m still grieving the loss of my own kitty friends.

My dog thinks computers are conspiring to get all of us, “the pack,” and doesn’t care about books or papers, but I miss having a cat stare at me while I was trying to get something done.

…A fine story…..hope it’s true too.

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment, or log in if you’re already a paid subscriber.