Last year my friend Tom Nissley appeared on Jeopardy!, winning eight straight games, which allowed him to quit his job as a Books editor at Amazon and earned him a spot in the Tournament of Champions, which was broadcast in November. Tom made it to the final round of the tournament, walking away with an impressive second place and his name in the record books as the third winningest player in Jeopardy! history. He’s now using his prize money to write a book or two, and sources say he sometimes appears as a ringer at a certain trivia night in his hometown of Seattle. I thought I’d invite Tom to talk about a movie with me. I chose the 1932 thriller about men hunting men, The Most Dangerous Game, because it had “Game” in the title and I thought that was funny.

Last year my friend Tom Nissley appeared on Jeopardy!, winning eight straight games, which allowed him to quit his job as a Books editor at Amazon and earned him a spot in the Tournament of Champions, which was broadcast in November. Tom made it to the final round of the tournament, walking away with an impressive second place and his name in the record books as the third winningest player in Jeopardy! history. He’s now using his prize money to write a book or two, and sources say he sometimes appears as a ringer at a certain trivia night in his hometown of Seattle. I thought I’d invite Tom to talk about a movie with me. I chose the 1932 thriller about men hunting men, The Most Dangerous Game, because it had “Game” in the title and I thought that was funny.

***

The Rumpus: What did you think of the movie?

Tom Nissley: I was thrilled by how short it was. I did a double take when I saw the running time on the Netflix sleeve: 1 hr, 3 min. Of course, all that meant was my wife and I could watch the commentary track right afterwards (we fell asleep halfway through, like we usually do). But I loved how fast the plot moved: we were giggling at how efficiently the opening shipwreck happened, and not (just) in a campy way.

With a movie like this, made to a different aesthetic standard than I usually look for, it can be interesting to try to separate the campy pleasures from the immediate ones. The camp is easy to spot, every time Count Zaroff strokes the scar on his forehead. But there were immediate pleasures too. The shipwreck is authentically disturbing, maybe because it happens more quickly than we expect, and even those stunt bodies falling into the water have an abruptness that makes you feel their impact. And even Zaroff, when he spouts his business about “after the hunt, then comes the love”: you don’t expect rape to be brought up so explicitly, but those were the pre-Code years. And the dogs, especially in the foggy swamp: the dogs don’t know they’re in a campy movie. There’s a moment when the hounds are climbing up a steep bank in an alarmingly powerful way and one can’t quite make it to the top and falls back while the others rush on from below him: that was probably the most moving sequence in the whole picture for me.

With a movie like this, made to a different aesthetic standard than I usually look for, it can be interesting to try to separate the campy pleasures from the immediate ones. The camp is easy to spot, every time Count Zaroff strokes the scar on his forehead. But there were immediate pleasures too. The shipwreck is authentically disturbing, maybe because it happens more quickly than we expect, and even those stunt bodies falling into the water have an abruptness that makes you feel their impact. And even Zaroff, when he spouts his business about “after the hunt, then comes the love”: you don’t expect rape to be brought up so explicitly, but those were the pre-Code years. And the dogs, especially in the foggy swamp: the dogs don’t know they’re in a campy movie. There’s a moment when the hounds are climbing up a steep bank in an alarmingly powerful way and one can’t quite make it to the top and falls back while the others rush on from below him: that was probably the most moving sequence in the whole picture for me.

But the legendary man-hunting-man sequence? That’s where it just got silly: it felt like a Road Runner cartoon, but with less tension. That’s where running out of money (as apparently they did) really did some damage.

I do love that Joel McCrea, though. What a fresh-faced young man.

What did you think? What cut through the camp for you?

Rumpus: The shipwreck was disturbing? I thought it was the funniest sequence of the whole movie. It reminds me of the time my dad and I were watching an old episode of Dr. Who at my grandparents’ house and there was this part where a guy gets crushed between two robot mummies. As my dad and I were cracking up, my grandmother came into the room, saw what we were watching, and said, “This isn’t scary to you?” It’s always interesting to me how movies we once considered suspenseful or fraught with a certain emotion can seem cheeseball to us now, owing to production values and pre-Method acting.

When did this film come out? 1932? It seems to me the whole thing is about Social Darwinism, which is interesting considering what was right around the corner, historically speaking. You’ve got your blonde, civilized hero (McCrea, who I loved in Sullivan’s Travels) up against the swarthy, scenery-chewing Zaroff and his gang of Cossacks. I’m not exactly saying that this is a pro-Aryan film, but there’s a whiff of xenophobia that hangs over the whole thing like a haze.

Nissley: Yes, the Aryan-Americans vs. the forces of darkness element is hard to ignore, especially when you pair MDG with the movie it was made alongside of, with the same directors and some of the same sets: King Kong. This kind of stuff would have been red meat for the grad-school cultural studies industry I used to be part of: it’s so unembarrassed about its anxieties and obsessions that you hardly know where to begin. Regarding Social Darwinism specifically, I thought on one hand it undercuts the “survival of the fittest” idea by making man-hunting-man so disgusting, to the point that now that McCrea, the great white hunter, knows what it’s like to be hunted himself, he seems to have lost his taste for blood. But I’m sure you could shoehorn it back into Social Darwinist ideas (as I understand them) by seeing Count Z as representing a decadent, savage race that will be superseded by fresh-faced, fair-play Americans like McCrea.

Speaking of grad school and Cossacks, here’s a background detail I absolutely love. Have you read The Possessed, Elif Batuman’s fabulously entertaining book on the writers and scholars of Russian literature? There’s a great little section in her chapter on Isaac Babel in which she realizes that “Frank Mosher,” an American airman who Babel describes interrogating in 1920 after he was shot down while fighting the Bolsheviks, was none other than Merian Cooper, the creator of King Kong and, yes, The Most Dangerous Game. (It appears, in fact, that Babel was the one who saved the future filmmaker from being killed by his Cossack comrades after he crashed.) Knowing that Cooper spent months as a prisoner of the Soviets (shoveling snow on the railroad, apparently) does add some color to his portrait of this mad, murderous Russian. And by the way, here’s Babel’s description of Mosher/Cooper from his diary: “A shot-down American pilot, barefoot but elegant, neck like a column, dazzlingly white teeth, his uniform covered with oil and dirt.” Sure sounds like Joel McCrea after he washes up on Ship-Trap Island!

Speaking of grad school and Cossacks, here’s a background detail I absolutely love. Have you read The Possessed, Elif Batuman’s fabulously entertaining book on the writers and scholars of Russian literature? There’s a great little section in her chapter on Isaac Babel in which she realizes that “Frank Mosher,” an American airman who Babel describes interrogating in 1920 after he was shot down while fighting the Bolsheviks, was none other than Merian Cooper, the creator of King Kong and, yes, The Most Dangerous Game. (It appears, in fact, that Babel was the one who saved the future filmmaker from being killed by his Cossack comrades after he crashed.) Knowing that Cooper spent months as a prisoner of the Soviets (shoveling snow on the railroad, apparently) does add some color to his portrait of this mad, murderous Russian. And by the way, here’s Babel’s description of Mosher/Cooper from his diary: “A shot-down American pilot, barefoot but elegant, neck like a column, dazzlingly white teeth, his uniform covered with oil and dirt.” Sure sounds like Joel McCrea after he washes up on Ship-Trap Island!

Another nice biographical tidbit, this time from the commentary track: “Ivan,” the mute Cossack brute in the count’s employ, was played by Noble Johnson, one of the few black actors in early Hollywood, who ran his own African-American studio, called the Lincoln Motion Picture Company, from 1916 to 1921.

I’m the kind of movie viewer who has IMDb open while I watch, and I love to make these connections outside the walls of the film, so feel free to run with them, but I’m also curious about how you watch a movie like this as a writer. Are you always looking for things you can take away–either bits of craft or actual shards of story or fact–and incorporate into the worlds you build in your fiction? Were there any raw materials you mined from this rich vein?

Rumpus: You truly are the master of trivia. I had no idea about the Babel connection, that’s amazing. I revisit Red Cavalry occasionally and assign him to students all the time. So fascinating to think that he crossed paths in such a dramatic way with Cooper, whose King Kong was the favorite movie of one Adolf Hitler (I’m pretty sure I know this thanks to the Genus edition of Trivial Pursuit). Have you read any of the propaganda Babel wrote? It’s terrifying, blood-thirsty stuff. My favorite line is “Stamp harder on the rising lids of their rancid coffins, Red Army fighters!”

I don’t know what “as a writer” really means anymore. I brush my teeth as a writer, I drive my car as a writer, I make dinner as a writer. I think, more broadly, your question is about incorporating influence. Every movie, book, album, etc. goes into the mulch pile to some degree. I latch on to some works more than others. The Holy Mountain by Jodorowsky, for example, was a film that deeply influenced my upcoming novel. But the more deliberate my attempts at drawing in an influence, the less influential that source becomes. Which is why I can’t seem to do research for anything I write, and sort of recoil at the very idea of research. Influences have to happen at the level of the subconscious, not as something deliberately sought out.

I’m interested in your movie digestive process as well. At least to the outside observer, it appears like your brain is full of hyperlinks. Like you’re webbing together all these pieces of information. This observation, I suppose, offers a sneaky opportunity for me to ask you about Jeopardy!. As I watched you clean up on that show, I wanted to get a sense for what was going through your head in the moment you hit the buzzer. Were there times when you hit the buzzer without actually knowing the question, and in the gap of time between when Trebek said your name and you had to speak, it came to you? Did you ever intuit that you might know the answer, so you buzzed in, having faith that your brain would catch up to your intuition?

Nissley: Hey, you’re not so bad at accessing the database either–look at you pulling out some excellent Babel facts of your own!

I know what you’re saying about being influenced by everything and nothing. I agree especially that the harder you try to incorporate something, the more it falls apart in your hands. To answer my own question, though (why else do we ask them?), one way I try to enjoy something like The Most Dangerous Game that has, for better or worse, almost no similarities to the way I tell stories is to look for material or techniques that I would never think to use on my own. A head floating in a vat? Maybe not. But the startling effect of action speeded up beyond our expectations, or the authentic animal presence of those unruly dogs? Those fragments I hope I can put aside somewhere in the storehouse to use when I need them.

Meanwhile, it all comes back to Jeopardy! (nice job remembering the exclamation point). What goes through my head before the buzzer? I’m trying to navigate that web of information as fast as I can. The mechanics of it are that I would try to read the clue faster than Alex and decide, by the time he got to the end, whether I knew the answer or not. One of my few strategies was not guessing at things I wasn’t pretty sure I knew, so if I couldn’t come up with an answer in time, I would just lay off the buzzer (which sometimes meant letting questions I could have gotten go by). Sometimes, though, I would be almost certain I “knew” an answer, even if I hadn’t articulated it to myself: neurologically, I guess I had navigated to the right spot in my memory, and knew the spot existed, but hadn’t accessed it yet. Usually, I was able to pull it up (once I remember desperately picturing Malcolm McDowell’s face and bowler hat while trying to pull out the words “Clockwork Orange“), but not always (like when I could only draw the first few syllables of “Savonarola” out of my brain in time). But those few seconds when you’re reading the question, trying to figure it out, and then getting ready to buzz: I’m not sure my brain has ever worked that well. I know I played a lot better on the show than I did at home, or even in rehearsals: there’s something about the adrenaline of the real game that finally pushed my brain to work at maximum capacity for a short time. There’s a thrill to operating in real time like that–it feels like the three-dimensional concentration when you have the ball in the lane in a basketball game, or when you’re part of the back and forth in a good conversation. And I think the speed of the game is one reason it’s so popular. There’s an electric flow to it that’s unlike, say, the more leisurely pub trivia games you and I have had the pleasure of playing a few times.

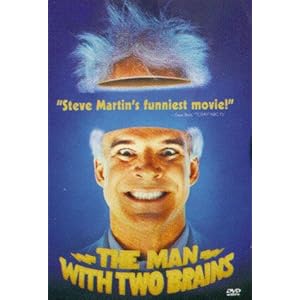

But meanwhile, it’s that web of information that makes Jeopardy! (and those fun facts we both pulled out about Babel and King Kong) seem less like trivia and more like knowledge. As a lot of people have pointed out, the more nodes you have on your network of knowledge, the more new facts stick, because they attach in various ways to the data that are already there. And so the main part of the fun for me of watching something like MDG is not the drama within the movie, but all the connections I can make to things outside the movie: to a good friend’s infatuation with Fay Wray, to hairstyles and fashions of another time (those high-waisted pants!), to The Man with Two Brains, to Gilligan’s Island, to the Bolsheviks and the Cossacks. And that’s why to me the DVD commentary track is perhaps the great new art form of the millennium.

That’s not always the case, though–there are other pleasures in other movies. In The Tree of Life, say, I didn’t get most of my enjoyment from thinking, “Oh, that’s Sean Penn, and just think of all the other stuff he represents.” In fact, within that movie, recognizing Sean Penn as Sean Penn was a drawback for me. But that movie wasn’t a hermetic experience either: the echoes of 2001 added to the experience for me, as did, I think, recognizing Brad Pitt as Brad Pitt, maybe because his character had enough weight to hold its own with the aura of Brad Pitt the star.

Rumpus: I can’t imagine doing anything but choking in Jeopardy!!!!! (Tell me, do you have to pronounce it with the exclamation point as well?) I figured everyone read the clue before Alex finished saying it. And since I have you on this subject, what’s the clicker like? From what I gather they’re the same technology as an old school Atari joystick.

What do you think is the difference between trivia and knowledge?

I watched The Tree of Life at home while suffering a cold, which is far from an ideal viewing experience. Oh yeah, and it was daytime, too. Even so, the cinematography blew me away, as has always been the case with Malick’s films. The way he makes plants look, the way he somehow manages to convey what the temperature of the air is in a scene. But I have to say what I most looked forward to was seeing those dinosaurs. And I wish one of them would have eaten Sean Penn. I love Sean Penn in nearly everything he does. There’s this lesser Woody Allen movie called Sweet and Low Down where I think he’s hilarious and brilliant. But between the interstellar screen saver sections of The Tree of Life, the guy just seemed adrift. I liked The Tree of Life but I was aware of myself wanting to like it, because liking it would prove to myself that I’m smart. I didn’t connect to it like I connected to The Thin Red Line or The New World. I though the scene where the whole cast meets on the beach was fairly cheeseball, like the series finale of Lost. And the “I give you my son” line annoyed me in a way that only an atheist who was raised Catholic can be annoyed. But any time Terrence Malick trains a camera on a weed, I’ll be happy to look at that all day long.

Nissley: At this point, I’ve said the word “Jeopardy” so much in the past year that it’s a little hard to reach the exclamatory. I think my usual intonation is closer to the interrobang. And yes, I think some early-’80s console experience with Combat or Missile Command is excellent training for mastering the “signaling device,” though the red button is at the top of the stick, not on the base, as with Atari.

The line between trivia and knowledge is in the eye of the beholder, but one way I think of it is that trivia is an obscure fact known for the sake of its obscurity (for example, Q: Who was on deck when Bobby Thomson hit the shot heard ’round the world? A: Willie Mays), whereas knowledge is a fact that you know organically as part of a larger structure of understanding (e.g., Q: Who is the only third-party presidential candidate since the Civil War to finish second? A: Teddy Roosevelt, 1912). But no doubt I’m just trying to paper over my own embarrassment at being a trivia champ by giving it a more respectable name. I did, after all, reveal to 10 million viewers that I know who Kim Kardashian was married to.

Now back to high art! I think I must have seen The Tree of Life under optimal conditions (although it was so long I had to go and pee in the middle, which I never do at the movies, but I figured I wouldn’t really miss any big plot points), because I just drank it down like water (maybe that’s why I had to pee). I’ve seen and enjoyed most of the Malick movies, but none have really gotten under my skin the way this one did. But “under my skin” is wrong–it felt like it was my skin. It wasn’t that I identified strongly with the story so much as the philosophy, which to my eyes expressed a sort of ecstatic sense of the world around us, and its unalterable impermanence. From what I’ve heard Malick fits his religious sense into some sort of Christianity, but I felt like I had never seen my own wide-eyed atheism embodied so profoundly before. As you said, it’s really a religion of the camera. My sister knows one of the cameramen Malick sent out to collect some of the non-story footage, and my understanding is that his mandate was pretty much: bring back beautiful stuff. I want that job.

But the Sean Penn sections, especially the laughable scene on the beach? I mostly pretend that they weren’t even in the picture. People who have told me how much they hated the movie tend to focus on those scenes, and I can’t really argue with them, except to say that I ignore them and am still left with my favorite movie (or probably anything) of the year.

I’ve never seen Sweet and Lowdown (I just can’t keep up with the Woodman), but the mention they made of it in passing in that recent PBS documentary on Allen made me want to track it down (along with a dozen other Woodys I’ve missed or half-forgotten).

Rumpus: Okay, Tom, one more for the road: This actor, who had a cameo appearance in Gravity’s Rainbow, in 2011 shared the sound stage with such creatures as Fozzie Bear, Miss Piggy, and Gonzo the Great.

Rumpus: Okay, Tom, one more for the road: This actor, who had a cameo appearance in Gravity’s Rainbow, in 2011 shared the sound stage with such creatures as Fozzie Bear, Miss Piggy, and Gonzo the Great.

Nissley: You’re going to end this with a stumper? Do I at least have until daybreak to answer it, like Joel McCrea? I can see you stroking your forehead wound now…

Well, I’m pretty sure Jason Segal’s not name-checked in Gravity’s Rainbow, but I haven’t taken my kids to The Muppets yet, so I have to think of who might still be alive that would have been big enough for Pynchon in the early ’70s. How about Kirk Douglas?

Okay, I looked it up: none other than “Judge Hardy’s madcap son,” Mickey Rooney. Well played. How about this in return? What actor, who had a slightly more pivotal cameo in The Moviegoer, is also the “actor / who died while he was drinking / he was no one I had heard of” in Suzanne Vega’s “Tom’s Diner” (and was Ron and Nancy Reagan’s best man)? (At least if IMDb is to be believed.)

Rumpus: I have no fucking idea.

4 responses

You the man, Tom Nissely.

You the man, Tom Nissley.

William Holden. Was the best man. How can you leave that unanswered?

Can we borrow him!? He did an amazing job. Our best man doesn’t do public speaking well at all, sadly.

Click here to subscribe today and leave your comment.