I walked in on Rob (not his real name), an ex-jock and Affleck-like Bostonian during a covert, one-man photo shoot in the men’s room at my new job this summer, and now—due to some untold mathematics of manliness—he’s my first uber-dude friend.

Rob drinks beers with his brothers and talks about sports and life in that circuitous way where a story becomes a metaphor for regret and fatherhood. At work, he quit asking pretty quickly how I felt about the Bruins when he saw the blankness in my eyes and the way I’d fumble trying to care, so he’d come by to shoot the shit about my commute instead, or complain affably about the weather, or to ask awkwardly how I was adjusting to my cross-country move or what exactly my wife did, again. He was nice, is what I mean, and we had nothing in common.

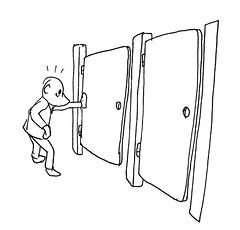

Our shared moment came at the end of the summer, a tender time in my transition. Four months in, my features were androgynous and, thus, restrooms dominated my life. Freud would have a field day with my situation, which involved a particularly complicated system meant to insure that I’d avoid my coworkers at least until I could get into the single stall and do my business. In an attempt to avoid weird moment with the guys from sales (“Wait! Is that the trans guy?” “I saw the trans guy come out of the stall!” I imagined them saying at their “closer” meeting on Tuesdays) I monitored the stall’s availability with weird vigilance, even pushing the door open and popping my head in just long enough to check for feet on the floor or a turned back at the adjacent urinal. Those were paranoid, heady times, when everyone knew I was trans but I wasn’t confident enough in myself yet to mind reminding them of the fact. Especially in any situation where my pants were down.

Things are different now. Do you know how long it takes to grow into an identity? I’d say six months is the most base level of comfort. It’s like coming into a second skin.

That day, I’d opened the door for the quick scan, but instead stumbled full-on into Rob in front of the full-length mirror, snapping pictures on his iPhone.

“Oh!” he said, guiltily. “Hey.”

Unable to walk by now that I’d been spotted, I moved into the restroom and tried to figure out how to seem like I had an intention that didn’t involve using the stall (wash my hands? Is that odd?) when I realized that the air between us was edgy. I tried to remember the etiquette. If there’s just one dude in the bathroom, doing something mysterious near the sink, do you turn and leave?

Unable to walk by now that I’d been spotted, I moved into the restroom and tried to figure out how to seem like I had an intention that didn’t involve using the stall (wash my hands? Is that odd?) when I realized that the air between us was edgy. I tried to remember the etiquette. If there’s just one dude in the bathroom, doing something mysterious near the sink, do you turn and leave?

We faced each other in the uncomfortably tight quarters. My spinning mind slowed when I noticed how uncomfortable he looked, beginning with the black stitches over the bridge of his nose.

“Hey,” I said, forgetting myself, “What are you doing?”

Something shifted as he indicated his face, explaining with reddening cheeks that he’d tripped over his daughter’s toys and landed on the side of a chair.

“I just thought I’d take a picture, you know, for Facebook,” he said. “But I can’t get the angle right. Or whatever.” He looked like I’d caught him jerking off. It felt intimate, one guy hiding out to do something in private without having to worry about other dudes giving him a hard time. It felt, in fact, familiar.

Sometimes I joke that my gender is “poet.” (I also joke that it’s “James Dean” but that’s less joke and more wishful thinking). I love the mystery bound up in gut instincts and the rough beauty available in the smallest moments. This nature is what showed me that I was a man, a curtain drawing back on my life in a dark moment, an internal bravery urging me to have faith in something deeper than sense or the body; something more than categories assigned at birth. I love what is available to you if you’re willing to read between the lines, and when I function from this raw space I see that I am just like everyone else, crafting a story beneath my words. Surprisingly, this has turned out to be my biggest asset in translating masculinity—knowing a metaphor when it stares you in the face.

“Uh,” I said, “do you want me to take it for you?” He nodded, without speaking. Male bonding, I thought, the flash lighting up his face.

It wasn’t a good picture, I noticed later, as I saw it go up on my Facebook feed. Rob’s friends commented on it jocularly nonetheless, asking about the state of the “other guy.” Rob “liked” each comment as it appeared, his virtual thumbs as vulnerable as my furtive glances under the stall.

Rob told me later and in passing that he’d hated having to quit playing baseball in college. I imagine how he liked being on a team, the euphoric camaraderie of a winning streak, the serious, gruffly affectionate coach, even the quiet nights after a hard loss. Sports are the ultimate metaphor, the tragedy and comedy and victory of a million Robs distilled into the shameful disappointment of a slump, the hot swell of hope when the bases are loaded, the satisfied cinch of a grand slam.

Now when Rob sees me in the hall, he calls me “man” with brotherly affection. I realize that he’s always seen me as one, even when I worried that no one did. Even before I had the confidence to believe in my own visibility, after so many years of living as myself only in my mind.

Rob did me a solid by highlighting his anxiety over my own. I don’t know if he realizes that, but I wouldn’t put it past him. I’ve since seen most of the guys at the sink or the urinal, and we head nod and move along. My voice is so deep that my chest vibrates when I sing along to the radio. I stopped hesitating awhile ago when I pushed the bathroom door open. I know who I am, and, anyway, whoever is on the other side is as naked as I am.

***

Rumpus original artwork by Jason Novak.